Tobacco Harm Reduction

The Statistics Relating to Smoking-Related Mortality and Morbidity Across the World

- No Fire, No Smoke: The Global State of Tobacco Harm Reduction

There are large differences between countries in the overall levels of smoking, and in the levels of smoking between men and women. According to WHO data for 2015, in 26 countries the prevalence of daily smoking amongst men is above 40 percent: in Indonesia, a staggering 65 percent of adult males smoke; 61 percent in East Timor; 57 percent in Tunisia; 51 percent in the Russian Federation and in Kiribati; 48 percent in Syria; 46 percent in Georgia and Armenia, 45 percent in Laos, Greece and Latvia; 44 percent in the Maldives and Egypt; 43 percent in the Solomon Islands and Ukraine; 42 percent in China, Papua New Guinea and Cyprus; 42 percent in Lesotho; 41 percent in Albania and Mongolia; and 40 percent in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, Bangladesh, Belarus and Micronesia.

These high levels persist despite major global initiatives led by the WHO to reduce smoking, and despite the investment of billions of dollars in tobacco control to reduce demand and supply.

That smoking has been in decline in much of the developed world is to be welcomed. But the fact that the steep drops since the 1970s have begun to level out in some countries demonstrates that despite all the efforts of tobacco control, even in the West, there are still millions of people who continue to smoke, most notably among the poorest and most vulnerable.

The situation is even more serious in LMIC, where most smoking deaths occur and where population growth is set to increase rather than decrease the smoking population. And it is precisely these poorer countries that simply do not have the resources to make serious inroads into their smoking problem. Overall, at the current levels, the WHO estimated in 2008 that by the end of the century, a billion people would have died from smoking at an annual cost to the global economy of US$1 trillion amounting to a projected total of US$92 trillion by 2100.

Yet there is now a proof of concept which offers a way for governments to tackle smoking-related deaths and disease and move towards the aspirations of the Sustainable Development Agenda, with no drain on national finances. Current safer nicotine products have the potential to replace and eradicate smoking. The history, development and growth in use of these products is the subject of the next chapter.

See also p. 17 of the report: No Fire, No Smoke: The Global State of Tobacco Harm Reduction 2018 — Global State of Tobacco Harm Reduction (gsthr.org)

Global E-Cigarette Regulation as of July 2018

Harry Shapiro - No Fire, No Smoke: The Global State of Tobacco Harm Reduction

It may come as a surprise to both those in tobacco control and those advocating for tobacco harm reduction that at present most countries do not have any specific law regulation regarding e-cigarettes: 101 countries have no specific law on e-cigarettes. It is possible that if it came to a government or court decision, it might be that in some of these countries e-cigarettes would be found to be covered by tobacco control legislation. However, this has yet to be determined in many countries. This includes many LMIC, where it is likely that e-cigarettes are not yet available or are only used by a minority.

At the other end of the spectrum there are 39 countries where the sale of e-cigarettes or nicotine liquids is banned. It is worth noting that rather like the failure of bans on recreational drugs to be effective, e-cigarettes are known to be available in at least 14 of these 39 countries. For example, e-cigarettes and nicotine are widely available and used in Australia. Some of the banning countries had pre-existing laws in which e-cigarettes and nicotine liquids were caught up – as again for example in Australia where the poisons regulations under the jurisdiction of the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) prohibit the unauthorised sale, possession and use of nicotine (see box). Several countries have a legal and regulatory framework for e-cigarettes, and this is generally a mix of a legal framework – often within the context of tobacco control legislation (as in the USA and Europe), plus product standards and legal or voluntary control over access to the products by young people. The most usual legislative route is to regard them as tobacco products, and/or as consumer products.

In most jurisdictions manufacturers are only allowed to promote e-cigarettes as safer than cigarettes and as aids to quitting if they are registered as medicinal products, similar to the regulations governing nicotine replacement therapies. In ten countries there is provision for medically regulated products.

See also p. 84 of the report: No Fire, No Smoke: The Global State of Tobacco Harm Reduction 2018 — Global State of Tobacco Harm Reduction (gsthr.org)

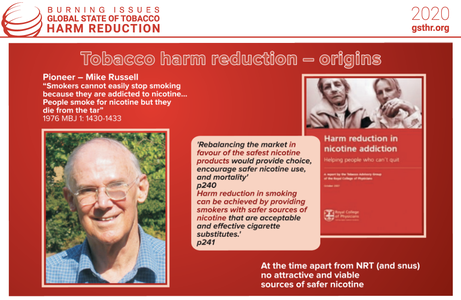

Tobacco Harm Reduction - Origins

- Burning Issues: The Global State of Tobacco Harm Reduction 2020

“The case is advanced for selected nicotine replacement products to be made as palatable and acceptable as possible and actively promoted on the open market to enable them to compete with tobacco products. There will also need to be health authority endorsement, tax advantages and support from the anti-smoking movement if tobacco use is to be gradually phased out altogether. It is essential for policymakers to understand and accept that people would not use tobacco unless it contained nicotine and that they are more likely to give it up if a reasonably pleasant and less harmful alternative source of nicotine is available. It is nicotine that people cannot easily do without, not tobacco. It will be assumed … our main concern is to reduce tobacco-related diseases and that moral objections to the recreational and even addictive use of the drug can be discounted providing it is not physically, psychologically or socially harmful to the users or to others.”

- Professor Michael Russell – consultant psychiatrist, Institute of Psychiatry, London.

See also p.24 of the report: Burning Issues: The Global State of Tobacco Harm Reduction 2020

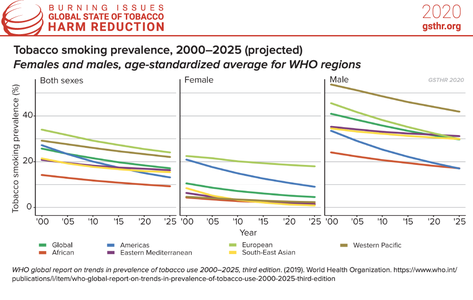

Tobacco Smoking Prevalence

- Burning Issues: The Global State of Tobacco Harm Reduction 2020

Historically, most countries have seen a rise and then a decline in smoking. A general decline in rates of smoking is apparent across all global regions, and for both sexes. This has been especially marked in many higher-income countries. Rates of smoking have fallen for both men and women largely due to greater public awareness of the importance of a healthier lifestyle, as well as the introduction of various tobacco control measures including advertising bans, smoke-free environments, and higher taxation. Nevertheless, reduction in smoking prevalence tends to start plateauing at around 20% of a population, suggesting diminishing returns on tobacco control interventions.

What these data show is that millions of people are still smoking, many of whom will want to, but have been unable, to quit. We discuss this in later chapters, where we consider the limits of tobacco control interventions and the need to adopt harm reduction measures for people who don’t want to smoke but want to continue using nicotine.

See also p.32 of the report: Burning Issues: The Global State of Tobacco Harm Reduction 2020

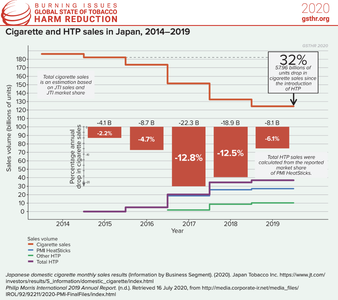

Cigarette and HTP Sales in Japan

- Burning Issues: The Global State of Tobacco Harm Reduction 2020

Heated tobacco products (HTP) now account for about a third of tobacco sales in Japan. There is a consensus around the following factors to account for this phenomenal rise matched against a dramatic fall in cigarettes sales:

» Interest in innovative technologies

» Relatively high levels of disposable income

» A paradoxical legal situation which on the one hand bans vaping products but on the other, not only allows HTP products to be sold, but gives the companies license to advertise and promote widely alongside a favourable tax regime.

» A cultural ethic whereby Japanese people are very considerate in health terms such that they embrace HTP over cigarettes as being less polluting and irritating to others. Consumer research in Japan revealed that the top two reasons for switching were not having to worry about unpleasant smells nor affecting others and also that they are less harmful than cigarettes.

See also p.51 of the report: Burning Issues: The Global State of Tobacco Harm Reduction 2020

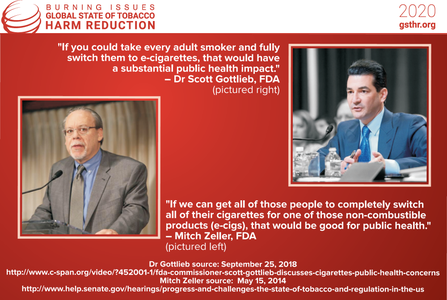

Individual Health to Public Health

- Burning Issues: The Global State of Tobacco Harm Reduction 2020

Much attention is given to ‘expert’ views on the use of safer nicotine products (SNP). Little attention is paid to the millions of ex-smokers who benefit from SNP and who will suffer should legislation grow increasingly prohibitionist.

Smoking per se is not a disease and even if many smokers wish they could quit (or at least wished that they wanted to quit), they do not regard themselves as ‘ill’ or ‘patients’ needing ‘treatment’.

The social, cultural and psychological dynamics of smoking are complex. In his book Ashes to Ashes, Richard Kruger eloquently explores what he calls the ‘protean usefulness’ of the cigarette, capturing the essence of the pleasure principle. This extract gives a flavour of what smokers are expected to give up and why they find it so hard, especially if they are long time smokers:

“The smoker smokes when he feels up or in the dumps when too harassed or overburdened or too unchallenged and idle, when threatened by the crowd at a party or when lonely in a strange place. A smoke is a reward for a job well done, consolation for a job botched. It can fuel the smoker for the intensity of life’s daily confrontations yet seem to insulate him from the consuming effects of any given encounter. It defines and punctuates the periods of the smoker’s day.”

See also p.56 of the report: Burning Issues: The Global State of Tobacco Harm Reduction 2020

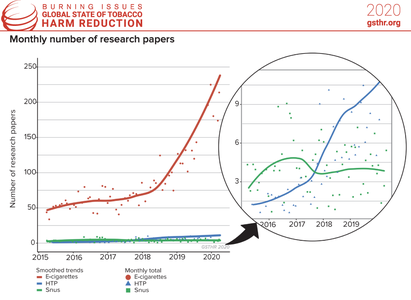

Monthly Number of Research Papers

- Burning Issues: The Global State of Tobacco Harm Reduction 2020

It is often said that little is known about vaping and its products. In fact, there has been a massive expansion in the number of scientific publications on vaping. In the six years from 2007-12, there were only 53 publications recorded. This number grew by 459 in 2015; 751 in 2016; 730 in 2017; 1,023 in 2018; 2,017 in 2019; and 793 up to April 2020, totalling 5,773 publications in peer-reviewed scientific journals. In the seven years from 2013 to 2020, the total covering vaping, heated tobacco products (HTP) and snus jumped to 6,309. There are fewer publications on other safer nicotine products (SNP). There were only three publications on HTP in 2015; 26 in 2016; 31 in 2017; 90 in 2018; 95 in 2019; and 48 in 2020. In total there were 293 publications on HTP between January 2015 and April 2020. On snus there were 27 publications in 2015; 61 in 2016; 47 in 2017; 42 in 2018; 53 in 2019 and 13 in 2020. In total, 243 publications on snus from January 2015 to April 2020.

But more science does not always mean better science or better science communication. Poorly formulated and designed research, over-cooked announcements of research results, over-hyped university press releases and an uncritical media with an appetite for bad news stories create confusion among the general public, smokers and users of SNP and health professionals. Taking a balanced view of any issue is not a question of giving equal weight to both sides but making a calculation based on the most robust and credible evidence. There is also a wider issue of what might be termed ‘nicotine illiteracy’ which goes beyond anti-THR rhetoric: a belief among health professionals and the public that nicotine is carcinogenic.

See also p.67 of the report: Burning Issues: The Global State of Tobacco Harm Reduction 2020

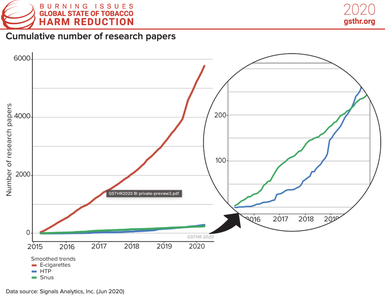

Cumulative Number of Research Papers

- Burning Issues: The Global State of Tobacco Harm Reduction 2020

There has been a massive expansion in the number of scientific publications on vaping in recent years. In the six years from 2007-12, there were only 53 publications recorded. This number grew by 459 in 2015; 751 in 2016; 730 in 2017; 1,023 in 2018; 2,017 in 2019; and 793 up to April 2020, totalling 5,773 publications in peer-reviewed scientific journals. In the seven years from 2013 to 2020, the total covering vaping, heated tobacco products (HTP) and snus jumped to 6,309. There are fewer publications on other safer nicotine products (SNP). There were only three publications on HTP in 2015; 26 in 2016; 31 in 2017; 90 in 2018; 95 in 2019; and 48 in 2020. In total there were 293 publications on HTP between January 2015 and April 2020. On snus there were 27 publications in 2015; 61 in 2016; 47 in 2017; 42 in 2018; 53 in 2019 and 13 in 2020. In total, 243 publications on snus from January 2015 to April 2020.

But more science does not always mean better science or better science communication. Poorly formulated and designed research, over-cooked announcements of research results, over-hyped university press releases and an uncritical media with an appetite for bad news stories create confusion among the general public, smokers and users of SNP and health professionals. Taking a balanced view of any issue is not a question of giving equal weight to both sides but making a calculation based on the most robust and credible evidence. There is also a wider issue of what might be termed ‘nicotine illiteracy’ which goes beyond anti-THR rhetoric: a belief among health professionals and the public that nicotine is carcinogenic.

See also p.67 of the report: Burning Issues: The Global State of Tobacco Harm Reduction 2020

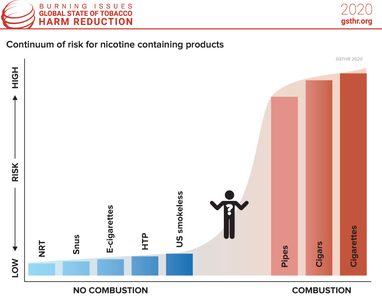

Continuum of Risk for Nicotine Containing Products

- Burning Issues: The Global State of Tobacco Harm Reduction 2020

In the context of tobacco harm reduction – what does ‘safer’ mean? When a smoker draws on a cigarette, the temperature at the tip rises from about 700 degrees centigrade to 900 degrees – enough to melt metals including aluminium and lead – releasing some 7,000 detected compounds, of which at least 70 are carcinogens. Tobacco is also combusted in cigars, cigarillos and pipes. It is these toxins which create (once water and nicotine are filtered out of the smoke) tar, which is one of the main factors contributing to cancer and other cardiovascular and respiratory diseases. No other way of consuming nicotine comes close to the dangers posed by smoking, as the chart below shows. Regarding vaping devices and based on a comprehensive evidence review, Public Health England (PHE) confirmed in its 2020 report their earlier conclusion that: “Vaping poses only a small fraction of the risk of smoking and switching completely from smoking to vaping conveys substantial health benefits over continued smoking. Based on current knowledge stating that vaping is at least 95% less harmful than smoking remains a good way to communicate the large difference in relative risk so that more smokers are encouraged to make the switch from smoking to vaping.”

With heated tobacco products (HTP), the situation is slightly different because tobacco is involved and is heated (at different temperatures depending on the device) although never above 350°C, and so below the combustion temperature of cigarettes. It is crucial to demonstrate that no combustion occurs with HTP. This can be done by showing that the devices work in the absence of oxygen. An independent assessment, conducted for New Zealand’s Ministry of Health, confirmed that no combustion occurs in the heated tobacco product IQOS when used as intended.

PHE and the UK Committee on Toxicity, Carcinogenicity and Mutagenicity of Chemicals in Food, Consumer Products and the Environment considered the available evidence in 2017. The UK Committee on Toxicity (COT) highlighted significant reductions in levels of harmful and potentially harmful constituents (HPHCs) in the aerosol of HTP compared to cigarette smoke and stated that “[t]here would likely be a reduction in risk for conventional smokers deciding to use heat-not-burn tobacco products instead of smoking cigarettes.” COT added that “[a] reduction in risk would also be experienced by bystanders where smokers switch to heat-not-burn tobacco products”.

Most of the scientific and clinical literature on HTP has been provided by the industry. However, the body of independent research on these products is growing. In 2018, PHE reviewed 20 extant studies (12 of which were the product of tobacco company research) and reiterated these points based on the available evidence and noted the potential of HTP: “Compared with cigarette smoke, heated tobacco products are likely to expose users and bystanders to lower levels of particulate matter and harmful and potentially harmful compounds. The extent of the reduction found varies between studies. […] The available evidence suggests that heated tobacco products may be considerably less harmful than tobacco cigarettes and more harmful than e-cigarettes.” Independent analytical chemistry studies on HTP have confirmed manufacturers’ findings showing that HTP products generate much lower levels of harmful constituents compared to tobacco cigarettes.

See also p.71 of the report: Burning Issues: The Global State of Tobacco Harm Reduction 2020

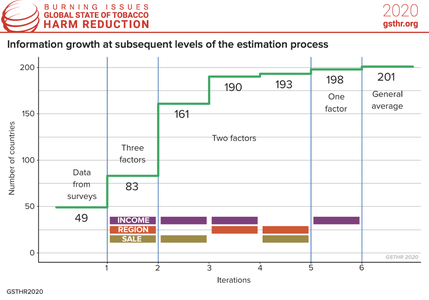

Information Growth at Subsequent Levels of the Estimation Process

- Burning Issues: The Global State of Tobacco Harm Reduction 2020

This infographic represents the statistical methods we used to estimate the global number of vapers in 2020 (see p.156 of the GSTHR report Burning Issues: The Global State of Tobacco Harm Reduction 2020). Based on the available information, we calculated the average prevalence of vaping for the WHO region, World Bank income classifications and legal status of the sale of e-cigarettes. Unfortunately, as we could guess, some groups are very poorly represented. Low-income countries are represented only by Uganda. Uganda is also the only data point for the African region. Similarly, we have only one data point from the South East Asia region with Bangladesh and the East Mediterranean region with the United Arab Emirates.

These three factors gave us four income groups, six regions and three sales statuses, which allowed us to separate 72 subgroups. For each of the groups the average prevalence of vaping was calculated. These 72 values were used as substitutes for the prevalence figures in the countries belonging to the group. Of course, not all subgroups were represented. For the first (1) – the most detailed, three-factor – subdivision we had information for only 13 subgroups, which allowed us to calculate estimates for 83 countries.

For the other countries, we had to use a two-factor breakdown covering all pairs of these three factors. A second (2) split was made on the basis of income groups and sales status, which gave us eight information cells covering 161 countries, a third (3) was made on the basis of income groups and regions with 10 information cells covering 142 countries and a fourth (4) was made on the basis of regions and sales status with nine information cells covering 102 countries. Last (5) subdivision was only based on one income groups factor.

The results of the calculations have been placed successively in the blanks remaining after the previous step. This means that the countries remaining without an estimated value after the first step have been assigned the values generated in the second step. In the third step we filled in the missing values remaining after the second step and in the fourth step remaining after the third step. All remaining gaps were filled with the fifth step.

We started with 49 known countries. The first step increased this number to 83, the next to 161, next to 190, the fourth one gave us only three more countries, increasing the number of countries to 193, and the fifth to 198. There were still three countries left. We attributed the average value obtained from all known countries to these countries.

See also p.151 of the report: Burning Issues: The Global State of Tobacco Harm Reduction 2020