Harm reduction, health and human rights

The everyday world of harm reduction

Harm reduction is a range of pragmatic policies, regulations and actions that either reduce health risks by providing safer forms of products or substances, or encourage less risky behaviours. Harm reduction does not focus exclusively on the eradication of products or behaviours.

In the course of everyday life, we all use or do things which could be dangerous. Many products or activities have been modified to reduce that risk. Modifications may come from manufacturers, regulators or be led by consumers.

Consider road safety. Many countries now have rules about wearing seat belts. Modern cars are designed with airbags which protect us in the event of a crash. Many riders wear cycle and motorbike helmets. Roads have speed limits. We don’t ban cars and bikes in case they cause harm to us or others. We adopt these measures to reduce harm, although they are called ‘health and safety’ rather than ‘harm reduction’.

Harm reduction as social justice

Harm reduction has another important aspect: a role in championing social justice and human rights for people who are often among the most marginalised in society.

Proponents of harm reduction argue that people should not forfeit their right to health if they are undertaking potentially risky activities, like drug or alcohol use, sexual activity or smoking.

The more political dimension to harm reduction grew out of the HIV/AIDs epidemic of the 1980s. At-risk and marginalised members of the gay and drug using communities in the USA and Europe acted in support of their own right to health, providing condoms and clean injecting equipment to their communities.

harm reduction champions social justice and human rights for the most marginalised

Over time, the benefits to public health were evidenced and more interventions of this kind were officially introduced by some governments. Eventually, they were endorsed by international health agencies. And it worked; those countries which embraced harm reduction as an important health strategy saw significant falls in HIV rates among affected communities. High risk populations benefitted, but so too did the general population.

When applied to these areas of human activity, there are several key principles in play. Harm reduction responses should:

- Be pragmatic, accepting that substance use and sexual behaviour are part of our world and choosing to work to minimise harmful outcomes rather than simply ignore or condemn them;

- Focus on and target potential harms rather than trying to eradicate the product or the behaviour;

- Be non-judgmental, non-coercive and non-stigmatising;

- Acknowledge that some behaviours are safer than others and offer healthier alternatives;

- Facilitate changes in behaviour by provision of information, services and resources;

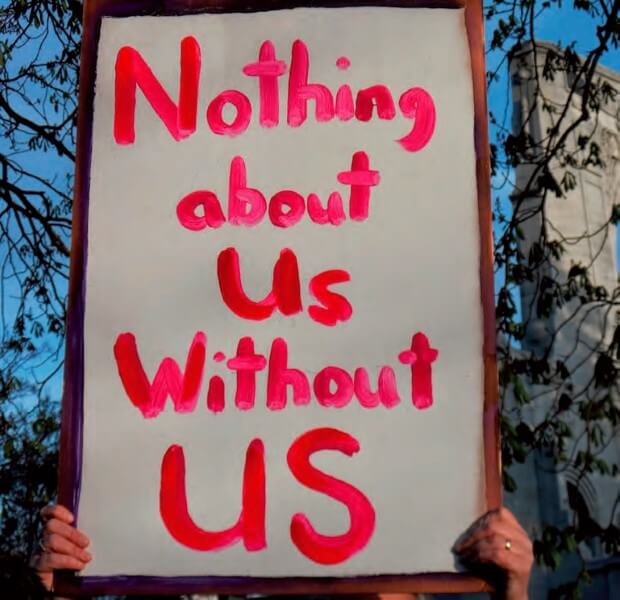

- Ensure that affected individuals and communities have a voice in the creation of programmes and policies designed to serve them – encapsulated in the slogan ‘nothing about us without us’;

- Recognise that the realities of poverty, class, racism, social isolation and other social inequalities affect people’s vulnerability to and capacity for dealing with health-related harms.

The intersection of harm reduction and human rights

While harm reduction as a social movement is relatively new, what affected communities have always been fighting for – the right to health, with nobody left behind – has long been enshrined in international conventions a nd continues to be so.

Harm reduction sits at the intersection between public health and human rights.

People have to be at the centre of decisions about their health; they need choice and to exert control over their own wellbeing. Behaviour changes will originate in, and be sustained, only if they fit with what people both want and are able to do.13

World Health Organization Constitution 1946:

“The enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of health is one of the fundamental rights of every human being without distinction of race, religion, political belief, economic or social condition.”

European Social Charter 1965:

“Everyone has the right to benefit from any measures enabling him to enjoy

the highest possible standard of health attainable”.

Article 11 requires states to take measures to prevent disease and to

encourage individual responsibility in matters of health.

The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, 1966:

Article 12 recognizes “the right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health” and that States Parties must take steps regarding “the prevention, treatment and control of epidemic, endemic, occupational and other diseases.”

Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion, 1986:

Aims to build public policies which support health such that health promotion is an agenda item in all areas of government and organisational policy-making. ‘Any obstacles to health promotion should be removed with the aim of making healthy choices the easiest choice’.

Millions of people smoke tobacco cigarettes every day in order to consume nicotine. There is now a range of ways to consume nicotine that are significantly safer.

People who smoke tobacco have the same fundamental right to enjoy the highest attainable standard of health as non-smokers. People who smoke therefore have the right to access accurate information and products that help them achieve this.