4: Barriers to health for all

The region faces a huge gap between the need for tobacco harm reduction and what is currently being achieved.

There are an estimated 743 million smokers in the region, but a lack of information about SNP uptake in the region. However, one indication of the need for tobacco harm reduction is the difference between the number of smokers and the number of nicotine vapers. Our best estimate is that there are only 19 million nicotine vapers in Asia in 2021. This suggests that there is only one nicotine vaper for every 39 cigarette smokers. We do not have comparable information on the number of users of other SNP in the region.

Disparity between the number of smokers and vapers in Asia

There is clearly an urgent need to expand access to appropriate SNP to reduce the impact of smoking in the region. What is holding up the adoption of safer nicotine products? We suggest that there are four interrelated factors preventing the development of THR policies and access to SNP.

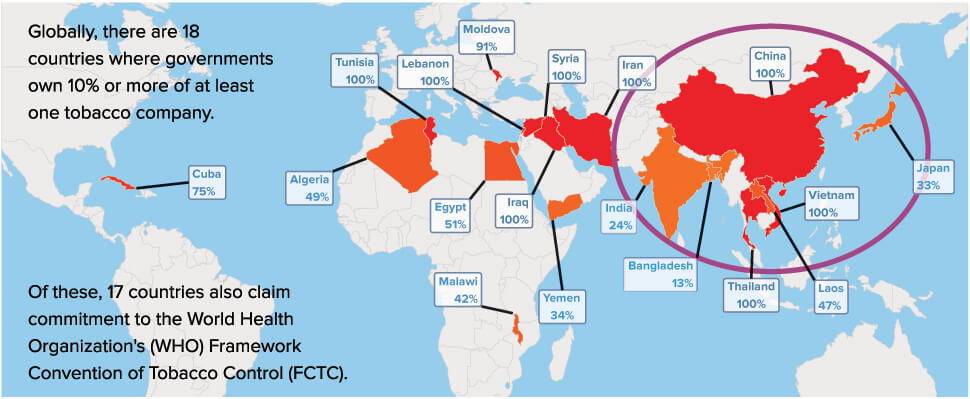

State-owned and state-involved tobacco companies

There are seven countries in Asia out of 18 globally, where the tobacco industry is either wholly owned by the state, or where the state has a significant percentage holding. At a national level, the economic benefits of being a tobacco producer and exporter, and the revenues derived from taxation are substantial for both China and India. In India, taxes on industry-manufactured, commercial branded cigarettes are some of the highest in the world, significantly higher than those levied on other, domestically produced combustible products such as bidis. This also serves to protect the market for non-cigarette tobacco production, as huge numbers of Indian tobacco consumers opt for SLT products. There are an estimated 22127 million smokeless product consumers against 253 million tobacco smokers.

7

the number of Asian countries where the state owns or has a

significant holding in a tobacco company

Within governments, those charged with overseeing the economy will often be at odds with colleagues overseeing the population’s health when it comes to tobacco control policies. No doubt industry will be aligned with some government officials – mainly from economic departments - in resisting or watering down proposals for tougher policies over smoking brought forward by health officials. Anti-tobacco campaigners are keen to point out where they believe industry has interfered in tobacco control policy in, for example, Indonesia and the Philippines, where the industry is in private hands.28 No such ‘interference’ is necessary in state-owned or state-involved companies. Commonly, health ministries are politically much weaker than those in charge of finance and the economy.

Most of the state-owned or state-involved tobacco companies are not involved in SNP production. There are some exceptions though. The Japanese government has a stake in Japan Tobacco International (JTI) which produces heated tobacco and vaping products29 while the Chinese National Tobacco Corporation has subsidiaries producing SNP.30

However, across most of the state-owned companies, senior company executives and officials in both finance and health departments are likely to be aligned when it comes to attempts to legislate against SNP or make access difficult or expensive. In China, the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology leads on tobacco control implementation and (through the State Tobacco Monopoly Administration) has responsibility for the Chinese National Tobacco Corporation.31 In Thailand, the government-owned tobacco company has a 100% tobacco domestic manufacture monopoly, while the government has enacted draconian anti-SNP laws.

There is a broad global attack against THR from the WHO, some governments and many of the international NGOs who have traditionally campaigned against smoking. This attack majors on alleged conflict of interest, claiming that THR academics, clinicians and advocacy groups are simply acting on behalf of tobacco companies to boost industry profits.

Yet a strange silence falls when it comes to the conflict of interest which sees a number of governments have a stake in the tobacco industry – yet also remain fully signed up to implementing the FCTC. There is a tension between Article 5.3 and one of its implementation guidelines, 7.2.

In Thailand, the government-owned tobacco company has a 100% tobacco domestic manufacture monopoly

Article 5.3 demands of Parties that they do not allow the tobacco industry to influence tobacco control policy and that all dealings are open and transparent. On this basis, there is a clear distinction between a Party to the FCTC on one side, and the commercial and other vested interests of the tobacco industry on the other.

Guideline 7.2 addresses the matter of state-owned tobacco, advising that “Parties with a state-owned tobacco industry should ensure that any investment in the tobacco industry does not prevent them from fully implementing the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control.”

But, by definition, a Party with a state-owned tobacco company has a vested interest. It cannot fully implement the FCTC 5.3. Either that, or to fully implement the FCTC, it must divest itself of the company into private hands.32

By definition, a Party with a state-owned tobacco company has a vested interest [and] cannot fully implement the FCTC 5.3

The WHO and its anti-THR allies avoid confronting this contradiction by focusing their attention entirely on multinational companies. On paper at least, you can’t have it both ways; but, it seems, the realities of political expediency are different.

Misinformation and propaganda

There is a culture of denial emanating from national and international scientific and medical organisations, particularly from the WHO, that despite the robust health evidence cited above, there are no benefits accruing from SNP. For example, in banning vaping products in 2019, an Indian government statement claimed that use “has increased exponentially and has acquired epidemic proportions in developed countries, especially among youth and children.”33 Based in Thailand, the South East Asian Tobacco Control Alliance (SEATCA) has partner agencies in Vietnam, Cambodia and the Philippines and is a regular source of anti-SNP propaganda across the region.

Anti-SNP rhetoric has reached a point where surveys show increasing numbers of smokers falsely believe that vaping products are as dangerous, if not more dangerous, than cigarettes. There are numerous examples of bad science where the methodology and conclusions about the dangers of SNP do not stand up to the most rudimentary scrutiny. In one notorious case which resulted in the paper being retracted, it was claimed that vaping caused heart attacks. It transpired that the heart attacks had happened before smokers switched to vaping.34

The war against SNP goes beyond simply misleading smokers, health professionals and the general public. The narrative has developed that the advent of SNP is a plot by the multi-national tobacco industry to hook young people into either smoking, or to a lifetime addiction to nicotine. Given the history of the industry in denying the bad effects of its products, such a narrative appears credible and has gained global traction. This same narrative is used to attack respected academics, clinicians and THR activists that their research and campaigning is working in the interests, directly or indirectly, of the tobacco industry. THR advocates are denied the chance to speak at or even attend some international conferences and are smeared publicly and in peer-reviewed journals.35

Increasing numbers of smokers falsely believe that vaping products are as dangerous, if not more dangerous, than cigarettes

In a recent example, the journal Tobacco Control, which is owned by the British Medical Journal, published a paper falsely alleging that the Thai consumer group ENDS Cigarette Smoking Thailand (ECST) was in the pay of a tobacco multinational to campaign in favour of THR and to end the ban on vaping products.36

The campaign against SNP in Asia has picked up the pace but would be limited in its reach and impact, if not for well-orchestrated and well-funded organisational interference from outside the region.

Western philanthropic interference

The WHO relies on voluntary donations from member states to run the organisation and its programmes. However, since the financial crash of 2007–08, member states have been unable to continue funding to the same levels. The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation stepped into the breach with substantial funding to help tackle communicable diseases like malaria. Meanwhile, Bloomberg Philanthropies has opted to pour millions of dollars into international tobacco control. Where the multinational tobacco industry has been accused of interfering in tobacco control policies, the charge can be laid equally at the door of western neo-colonial philanthropy, interfering to encourage and facilitate a prohibitionist approach to SNP.

The WHO Tobacco Free Initiative has benefited directly – and could barely function without – substantial Bloomberg Philanthropies funding. Its grantees, like the USbased Campaign for Tobacco Free Kids (CTFK) and the Paris-based International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease (The Union) have embarked on a campaign to encourage LMIC to go for outright SNP bans.37 The World Bank designates the majority of Asian countries as middle-income countries.

The thrust of the campaign is that LMIC need not bother with independent assessment of the health evidence pertaining to SNP, but simply institute bans, on the grounds that regulation is too complicated for health systems with fragile infrastructures.

Where the multinational tobacco industry has been accused of interfering in tobacco control policies, the charge can be laid equally at the door of western neo-colonial philanthropy, interfering to encourage and facilitate a prohibitionist approach to SNP

Simultaneously, they are also encouraging LMIC to invest in NRT, which the evidence shows is relatively ineffective. In December 2020, the WHO launched a ‘Commit to Quit’ campaign with a target of getting 100 million smokers to quit smoking. The WHO website announced that, “WHO, together with partners, will create and build-up digital communities where people can find the social support they need to quit. The focus will be on high burden countries where the majority of the world’s tobacco users live”.38 This suggests that Asia will figure heavily in campaign efforts and these ‘partners’ include four companies trading in NRT products.

Within Asia, Bloomberg Philanthropies has also funded the Global Center for Good Governance in Tobacco Control (GGTC) to run a ‘knowledge hub’, responsible for monitoring tobacco company interference and the implementation of Article 5.3. The GGTC has links to SEATCA, also in receipt of Bloomberg Philanthropies funding.

GGTC took tobacco industry ‘monitoring’ to ludicrous lengths when they organised a poster competition for under 18s. Entrants had to confirm they and their family had no links to the tobacco industry going back to great-great grandfathers, or third cousins three times removed.

The paradox of campaigning against tobacco company policy interference has been starkly exposed in the Philippines. There is a parliamentary investigation under way in the Philippines into Bloomberg Philanthropies’ funding of the Philippine Federal Drug Administration and undue influence on national tobacco control measures and responses to SNP (see Philippines national case study).

The Indian government has also reacted negatively to reports that Bloomberg Philanthropies have been channelling funds in support of NGOs campaigning against THR and India’s national tobacco control policies.39

Regulation and control

The existence of state-owned or state-involved tobacco companies, misleading medical information and foreign-funded attacks on THR and SNP have influenced the regulatory landscape in the region. That said, the control picture is very mixed. Having laws in place is one thing; implementation and enforcement are often far bigger challenges.

- In Brunei, vaping devices are controlled both as medicinal and tobacco products, yet it is illegal to use or import them.

- In 2019, China banned online sales of vaping products within the country.

- Cambodia, India, Thailand and Singapore have banned production, manufacture, import, export, transport, sale, distribution, and advertising of vaping products. Cambodia and Singapore have extended the ban to include use of vaping products, which in the case of Cambodia, now extends to a comprehensive ban on HTP.

- Vietnam is considering a ban on production, sale and import of vaping products.

- In June 2020, the Hong Kong government stepped back from imposing what would have been a comprehensive ban on all SNP. To date, there have been no further developments.

- The Indonesian government originally tried to enforce a blanket ban on vaping, but it was so regularly flouted that they moved to a licensing regime. Here, a 57% excise tax has been imposed on vaping, but more to protect the dominant local combustible kretek economy, accounting for 95% of all cigarettes smoked.

- In Malaysia, vaping devices are technically regulated as medicinal products, but are widely available. HTP are also widely available, but not subject to technical medical regulations.

- South Korea has imposed high levels of taxation on HTP and generally taken a backward step away from THR in launching anti-vaping campaigns. Sales of HTP have not recovered to date. The irony is that South Korea’s domestic tobacco company has proved highly innovative in developing new combustible tobacco products, such as sweet flavours and products producing less odour. The company will likely benefit from tighter restrictions and public antipathy towards SNP.

- In the Philippines, proposals for excessive tax increases on SNP would render them unaffordable for most smokers.

- Myanmar has no specific SNP regulations, while Laos controls vaping devices as tobacco products, but neither appear to have specific laws relating to HTP.

- In Taiwan, vaping devices have slipped through a legal loophole. As they do not contain tobacco, they fall outside the current tobacco control laws. Proposals for a total ban in 2017 do not appear to have been enacted.

In most countries in the region where it is legal to sell, buy and use SNP, they are nevertheless treated as tobacco products, which not only imposes bans on use in public places, but prohibits any promotion of SNP as a safer option to smoking.

There appear to be no restrictions in the region on the use of Swedish-style snus. However, any safer SLT products need to be acceptable to millions of smokeless tobacco users who have been accustomed to cheap, locally produced and homemade products going back many centuries. There is also considerable economic investment in more commercially produced products. However, the uptake of appropriate products could have a significant role in reducing the disease and death tolls from oral cancers.

National case studies

Thailand

As of 2014, it became illegal to import vaping products. In 2015 this was followed by a ban on in-country sales under consumer protection legislation. There would be an option to allow vaping products under the Tobacco Products Control Act (TPCA), although that same act could be used to strengthen the existing ban.

Despite the laws, vaping products are widely sold, creating opportunities for extortion by corrupt government officials. In 2017, the market value was estimated at more than 6 billion baht ($200m US) per year, with an estimate this could double annually. But owing to prohibition, the government cannot collect the tax on these products as income for the State.

THR activists are under threat of legal action: TPCA Section 35 specifically prohibits any activities that could affect the tobacco control policy, which includes campaigning for a law change on SNP.

While the government majors on the public health risk of SNP to justify bans, promoted heavily by anti-THR organisations in the country, economic factors also play a significant role in anti-THR politics. The state-owned Tobacco Authority of Thailand (TOAT) has a monopoly of domestic tobacco manufacture and controls 70% of the tobacco market. However, there is a trade agreement in place with the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN) which allows tobacco imports from those countries. It is arguable that the ban on SNP has been enacted more to stop commercial threats from imported products than on simply public health grounds.

In addition, beside mainstream and factory-produced cigarettes, there is a local hand-rolling tobacco product called Ya-sen which has been around for hundreds of years. Because of its cheap price, it has been heavily used especially in lowincome groups. It is unlikely that the Ya-sen market would ever be seriously challenged by the SNP market because of the significant price differences between the products.

Philippines

Vaping products have been available in the Philippines for more than a decade: HTP have been recently introduced. The number of vapers is estimated at around 800,000. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, there were also more than 800 vaping stores in the country.

The regulatory environment towards SNP has become increasingly hostile. President Duterte, a former smoker, contracted Buerger’s disease, a serious circulatory condition to which only smokers seem to be prone. In 2017, he stated that smokers “should be eradicated from the face of the earth”. He followed up in November 2019, with a verbal order to ban the use of vaping products, which emboldened the police to arrest hundreds of vapers and confiscate vaping devices and juice packs. This stemmed from inaccurate information fed to the president by the Department of Health, linking the illness of a 16-year-old girl in Central Visayas, a region in the Philippines, to vaping-associated lung injury which was the subject of significant attention in the United States and worldwide at that time.

FDA controversy

The Philippines Food and Drug Administration (FDA), an attached agency of the Department of Health (DOH), was tasked with issuing the implementing guidelines for SNP laws. The regulator has yet to publicly release the guidelines after the initial draft issued in October 2020 became highly controversial.

Under the FDA’s initial draft, any company engaged in any aspect of the SNP business had to get market authorisation from the FDA. In other words, SNP were to be treated as medicinal products on the grounds that no products had been approved for cessation by the WHO or the Philippines National Regulatory Agency.

The FDA then conducted online public consultations on the guidelines. It was during these hearings that an official admitted that the FDA had received $150,000 from Bloomberg Philanthropies via The Union.40

Two members of the House of Representatives who participated in the dialogues called for the suspension of FDA hearings. In December 2020, they filed a resolution directing the House Committee on Good Government and Public Accountability to conduct an inquiry into the alleged “questionable” receipt of private funding by the FDA in exchange for specific and predefined policies against a legitimate industry.

At the time of writing, neither The Union nor Bloomberg Philanthropies have commented on the issue. However, The Union has publicly admitted that it has been working with the Philippines’ Department of Health for over a decade to “develop and promote legislation and policies that comply with the Philippines’ commitments under the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, including Article 6 on implementing tax and price measures to reduce the demand for tobacco.” However, as much of the western-derived tobacco control funds are now focused on pushing through anti-THR legislation, interference is moving beyond simply ‘reducing the demand for tobacco’.

Meanwhile, consultations have been taking place to determine the proposed tax formula for SNP. As it stands, this would involve products becoming more expensive and further deterring smokers to switch away from smoking.

Malaysia

Since November 2015, there has been a ban on e-liquids containing nicotine, meaning that legally only non-nicotine liquids have been allowed for use with vaping devices. However, the Malaysian consumer activist group Harm Awareness Association (HRA) estimates that 90% of Malaysian vapers use nicotine e-liquid and there is no discernable enforcement of the law. Despite the occasional crack-down, nicotine e-liquid remains widely available both in vape shops and online.

The government is now enacting a new tobacco control law to include nonnicotine vaping devices and liquids with a general tobacco law to prohibit promotion and advertising, use by minors and smoking and vaping in public spaces. The new law also introduced excise taxes, license requirements and attendant fees for the manufacture and warehousing of non-nicotine vaping products.

The new law is unlikely to make any difference to the existing (and largely nonenforced) ban on nicotine e-liquid. So HRA are calling for the excise duty to be extended to nicotine products, in effect pointing out to government that as most vapers are technically breaking the law with impunity, why not legalise the products – and collect revenue?

India

A vaping product sales ban has been in force since late 2019, although personal use is allowed. In January 2020, the government also barred anyone from carrying vapes through airports, whether for personal use or not. Even though personal use is not prohibited, there are regular reports of vapers being harassed by police who do not fully understand the law or are intentionally misinterpreting it for the purpose of extracting bribes.

While the ban may not have significantly affected current users, it has impacted would-be switchers, removed safety nets for sales to minors, and negatively affected the image of vaping. Many people now see it as an illegal activity which is more harmful than smoking.

The Indian government has also effectively banned any research into THR products and, under pressure from Bloomberg Philanthropies-funded groups, has barred government institutions from working with anyone linked to the Foundation for a Smoke-Free World.

Bloomberg Philanthropies-funded groups such as the Union and CTFK directly fund state and national tobacco control programmes. This gives them immense sway on policymaking. CTFK funded a law college to produce a tobacco control policy document, which was subsequently adopted by the health ministry in its proposals for a new tobacco control bill.41 However, the government appears to be sensitive to this type of foreign funding and has said that there will be more surveillance of NGOs.42

Over 90% of tobacco consumption is represented by traditional products like chewing tobacco, bidis, khaini and illegally smuggled cigarettes. This poses unique challenges for THR. While bans are in place against ST as part of general tobacco control legislation, the primary focus of India’s tobacco control efforts is on the minority use of legal cigarettes – higher taxes (legal cigarettes contribute 80% of tobacco tax revenue), use restrictions, public messaging and so on. By contrast, traditional tobacco products are cheaply available and subject to little or no control.43

There is also the political component since large parts of tobacco trade is controlled by politicians or their backers, which makes implementing THR solutions difficult unless they can be encouraged to participate.

State tobacco companies say they want to be able to sell THR products and in their annual reports state they have made significant investments in developing them.44 However, they have done nothing to oppose anti-SNP legislation or counter government misinformation. The country’s largest tobacco farmers’ union, traditionally linked to/controlled by the cigarette monopoly ITC, has publicly supported the ban. Stock prices of tobacco companies have risen following announcements about stricter SNP controls.

Bloomberg Philanthropies-funded groups such as the Union and CTFK directly fund state and national tobacco control programmes

- National Cancer Institute and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2014). Smokeless Tobacco and Public Health:

A Global Perspective (No. 14–7983; NIH Publication). MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for

Disease Control and Prevention and National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute.

https://untobaccocontrol.org/kh/smokeless-tobacco/wp-content/uploads/sites/6/2018/06/

SmokelessTobaccoAndPublicHealth.pdf and Drope, J. et al. (2018). The Tobacco Atlas (6th ed.). American Cancer Society and Vital Strategies. - For example: Astuti, P. A. S. et al. (2020). Why is tobacco control progress in Indonesia stalled? – a qualitative analysis of

interviews with tobacco control experts. BMC Public Health, 20(1), 527.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-08640-6. Alechnowicz, K., & Chapman, S. (2004). The Philippine tobacco industry: “the strongest tobacco lobby in Asia”. Tobacco Control, 13(suppl 2), ii71–ii78. https://doi.org/10.1136/tc.2004.009324 - Reduced-Risk Products – our vaping products | Japan Tobacco International – a global tobacco company. (n.d.). Retrieved 24 March 2021, from https://www.jti.com/about-us/what-we-do/our-reduced-risk-products

- China Tobacco competes for the e-cigarette market in 2020 • VAPE HK. (2020, August 23). VAPE HK. https://vape.hk/china-tobacco-e-cigarette/

- Wan, X. et al. (2012). Conflict of interest and FCTC implementation in China. Tobacco Control, 21(4), 412–415. https://doi.org/10.1136/tc.2010.041327

- Malan, D., & Hamilton, B. (2020). Contradictions and Conflicts: State ownership of tobacco companies and the WHO

Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Just Managing Consulting.

https://www.smokefreeworld.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Contradictions-and-Conflicts.pdf - India’s government approves ban on e-cigarettes. (2019, September 18). AP NEWS.

https://apnews.com/article/2dcf235b0f9d4f68a1db9f1555244904 - McDonald, J. (2020, February 20). Journal Retracts ‘Unreliable’ Glantz Study Tying Vaping to Heart Attacks. Vaping360. https://vaping360.com/vape-news/88729/journal-retracts-unreliable-glantz-study-tying-vaping-to-heart-attacks/

-

For detailed information on this issue, please see Chapter 5, pp.91-112 of Shapiro, H. (2020). Burning Issues: Global State

of Tobacco Harm Reduction 2020. Knowledge-Action-Change.

https://gsthr.org/resources/item/burning-issues-global-state-tobacco-harm-reduction-2020.

Read the chapter online at: https://gsthr.org/report/2020/burning-issues/chapter-5 - Patanavanich, R., & Glantz, S. (2020). Successful countering of tobacco industry efforts to overturn Thailand’s ENDS ban. Tobacco Control. https://doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2020-056058. A formal complaint has been lodged. No response at the time of writing.

- Where bans are best. Why LMICs must prohibit e-cigarette and htp sales to truly tackle tobacco. (2020). The Union. The International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease.

- WHO launches year-long campaign to help 100 million people quit tobacco. (2020, December 8). https://www.who.int/news/item/08-12-2020-who-launches-year-long-campaign-to-help-100-million-people-quit-tobacco

- Michael Bloomberg turns the dial on Indian health policy – The Economic Times. (2021, March 19). https://m.economictimes.com/industry/csr/initiatives/michael-bloomberg-turns-the-dial-on-indian-health-policy/amp_ articleshow/81589378.cms?s=03

- FDA admits getting over $150,000 from anti-tobacco NGO to regulate vapes – Manila Standard. (2021, March 17). https://manilastandard.net/index.php/business/biz-plus/349714/fda-admits-getting-over-150-000-from-anti-tobacco-ngo-toregulate- vapes.html

- Ashok R. Patil. (2020). Report on Tobacco Control Law in India – Origins and Proposed Reforms. National Law School of India University. https://www.nls.ac.in/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Tobacco-Control-Book-Final-proof-to-print.pdf

- Michael Bloomberg turns the dial on Indian health policy – The Economic Times. (2021, March 19). https://m.economictimes.com/industry/csr/initiatives/michael-bloomberg-turns-the-dial-on-indian-health-policy/amp_ articleshow/81589378.cms?s=03

- India Country Report. (2020). Foundation for A Smoke-Free World.

https://www.smokefreeworld.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/India-Country-Report-1.pdf - Enduring Value. (2019). [Report and Accounts]. ITC Limited.

https://www.itcportal.com/about-itc/shareholder-value/annual-reports/itc-annual-report-2019/pdf/ITC-Report-and- Accounts-2019.pdf P.44