Burning Issues: Global State of Tobacco Harm Reduction 2020

©Knowledge-Action-Change 2020

ISBN 978-1-9993579-5-5

Written and edited by Harry Shapiro

Data compilation and analysis: Tomasz Jerzynski

Report and website production coordination: Grzegorz Krol

Consumer interviews: Noah Carberry

Copy editing and proofing: Tom Burgess

Report design and layout: WEDA sc; Urszula Biskupska

Website design: Bartosz Fatyga and Filip Wozniak

Print: WEDA sc

Project management: Professor Gerry Stimson, Kevin Molloy and Paddy Costall

The report is available at https://gsthr.org

Knowledge-Action-Change, 8 Northumberland Avenue, London, WC2N 5BY

© Knowledge-Action-Change 2020

Citation:

Burning Issues: Global State of Tobacco Harm Reduction 2020.

London: Knowledge-Action-Change, 2020.

The conception, design, analysis and writing of Burning Issues: The Global State of Tobacco Harm Reduction 2020 was undertaken independently and exclusively by Knowledge-Action-Change.

It was produced with the help of a grant from the Foundation for a Smoke-Free World, Inc.. The contents, selection and presentation of facts, as well as any opinions expressed herein, are the sole responsibility of the authors and under no circumstances shall be regarded as reflecting the positions of the Foundation for a Smoke-Free World, Inc..

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to a number of people who independently offered information, comments and suggestions for the report. These include:

David Abrams, Professor of Social and Behavioral Sciences, School of Global Public Health, New York University, USA.

Greg Conley, President of the American Vaping Association, USA.

Dr Marewa Glover, Director of the Centre of Research Excellence on Indigenous Sovereignty and Smoking, New Zealand.

Will Godfrey, Editor, Filter Magazine, USA.

Chris Lalonde, Professor of Psychology, University of Victoria, Canada.

Nancy E. Loucas, Director, Paraclete Associates Ltd, New Zealand.

Shane MacGuill, Senior Head of Tobacco Research, Euromonitor, UK.

Bernhard-Michael Mayer, Professor of Pharmacology, University of Graz, Austria.

Michelle Minton, Senior Fellow, Competitive Enterprise Institute, USA.

Chimwemwe Ngoma, Project Manager, THR Malawi, Malawi.

Uche Olatunji, Country Director, THR Nigeria, Nigeria.

Dr Sudhanshu Patwardhan, Director of Policy, Centre for Health Research and Education, UK.

Tim Phillips, Managing Director, ECigIntelligence, UK.

Riccardo Polosa, Professor of Internal Medicine, specialist of Respiratory Diseases and founder of the Center of Excellence for the acceleration of Harm Reduction at the University of Catania, Italy.

Brad Rodu, Professor of Medicine, University of Louisville, USA.

Dr Roberto Sussman, Institute of Nuclear Sciences, National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) and Director of Pro-Vapeo Mexico, Mexico.

David Sweanor, Adjunct Professor, Faculty of Law, University of Ottawa, Canada.

Mark Tyndall, Professor of Population and Public Health at the University of British Columbia, Canada.

Dr Alex Wodak, Board Director, Australian Tobacco Harm Reduction Association, Australia.

Executive Summary

Tobacco harm reduction

The central theme of this report, enshrined in many international treaties, is the universal right to health, including for those who for whatever reason continue to engage in risky behaviours. Harm reduction refers to a range of pragmatic policies, regulations and actions which either reduce health risks by providing safer forms of products or substances, or encourage less risky behaviours. Harm reduction does not focus primarily on the eradication of products or behaviours.

The humane response, instead, is to reduce the risks, thereby enabling people to survive and live better – in this case through access to safer nicotine products (SNP) aimed at encouraging people to switch away from cigarettes, one of the most dangerous ways of consuming nicotine.

The global smoking problem continues unabated, but there are glimmers of hope in some countries

The World Health Organization (WHO) has not revised downwards its estimate that one billion lives could be lost to smoking-related disease by the end of the century. This is equivalent to the combined populations of Indonesia, Brazil, Nigeria, Bangladesh and the Philippines dying from COVID-19.

And while daily adult smoking levels have fallen across the world, the rates of decline have slowed in some countries. In others, the numbers of smokers have increased, often due to population growth. The highest reported levels of smoking occur mainly but not exclusively in low and middle-income countries (LMIC) which consequently shoulder the heaviest burden of disease and mortality. There are 22 countries where 30 per cent or more of the overall adult population are current smokers. These countries include Pacific islands such as Kiribati and the Solomon Islands, several European countries including Serbia, Greece, Bulgaria, Latvia and Cyprus, Lebanon in the Middle East, and Chile in South America.

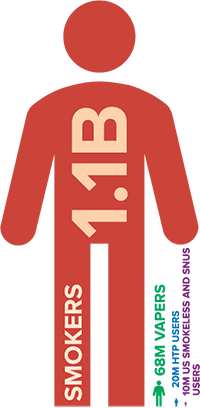

The estimated total number of smokers globally – at 1.1 billion – is static, the same number as in 2000 and predicted to be the same in 2025, disproportionally affecting poor and marginalised groups, especially in LMIC.

The WHO continues to express concern that the unabated levels of smoking will undermine attainment of the Sustainable Development Goals and ensure that the 2030 targets to reduce levels of non-communicable disease will be missed. Clearly then, traditional tobacco control interventions elaborated in the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) are not enough. Tobacco harm reduction (THR) policies therefore should be regarded as complementary rather than inimical to reducing the global death and disease from smoking. The glimmer of hope is that some countries have taken a more inclusive approach to THR as part of the overall strategy towards a smoke-free world.

New product development...

Product innovation continues to offer a wide choice to adult consumers looking to avoid smoking. The origins of vaping lay outside the orbit of tobacco multinationals and the creative disruption this caused was underlined by the success of JUUL, which, since 2018, rapidly overtook its rivals. Some of JUUL’s early marketing to the young adult end of the smoking market clearly caused controversy, but the product delivered a nicotine experience sought by many in the wider market of adult consumers.

Vaping devices, already discreet and easy to use, are becoming technologically more sophisticated, making the term ‘e-cigarette’ increasingly redundant. More companies are involved in developing heated tobacco products (HTP), while new non-tobacco nicotine products are also coming onto the market.

...but the global number of SNP users remains small

Despite a more globally hostile environment for THR, our exclusive survey of global prevalence of SNP estimates that the overall figure stands at approximately 98m, of whom 68m are vapers. While from a public health perspective this is good news, it still means that after more than a decade of product availability, there are only nine users of SNP for every 100 smokers.

What is happening in different countries?

The highest number of vapers live in the United States, China, the Russian Federation, United Kingdom, France, Japan, Germany and Mexico. Japan has the highest number of HTP users while Sweden and the US have the highest number of snus consumers. Use of SNP is holding up in countries such as the UK, Norway, Sweden, Iceland and Japan, although in the latter country, sales of HTP have slackened, possibly due to the number of early/younger adopters reaching saturation point.

The evidence confirms that safer nicotine products are just that – safer than smoking

There is no such thing as absolute safety, but the newer SNP have been in wide circulation for more than a decade, with accumulated evidence that they are much less risky than combustibles. Certainly since 2018, no robust evidence has emerged to throw doubt on the widely quoted conclusion of Public Health England that vaping is at least 95 per cent less risky than smoking and that emissions pose a negligible hazard to bystanders. Similarly, the relative safety record of Swedish-style snus and US smokeless products is unchanged from 2018. Moreover, there is growing evidence that use of SNP is more effective for smoking cessation than nicotine replacement therapy (NRT). This means over-interpretation of the ‘precautionary principle’ (the exercise of caution in the face of potentially harmful innovation) relating to health advice and regulation concerning SNP is no longer tenable.

Other concerns have been raised about the use of SNP. Misleading data from the US promoted the idea that JUUL was responsible for an epidemic of vaping among young people through the marketing of ‘child-friendly’ flavours, whereas more sober evaluations demonstrated that ‘use’ was very broadly defined covering experimentation and much rarer daily use. Lung injury and deaths in the USA were quickly determined by consumers and local health authorities (as opposed to US federal agencies) to be caused by the vaping of illicit tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) liquid, not industry-standard nicotine liquid.

After decades of tobacco research which failed to demonstrate adverse effects of nicotine on the developing brain, recent claims to this effect about vaping are not credible. Failing to demonstrate a gateway effect from vaping to smoking, anti-THR campaigners majored on nicotine ‘addiction’. However, given the lack of evidence about the physical and psychological harms of nicotine, concerns about ‘addiction’ belong more to the realm of moral objections than public health. Finally, and without any evidence, it has been claimed that vaping puts users more at risk from COVID-19.

More science doesn’t necessarily mean good science

Since 2010 there has been an explosion in the number of studies from all disciplines looking at all aspects of the use of SNP. An internet search reveals that from 2007–2012 only 53 scientific papers were published on vaping. By 2020, the numbers of published papers covering all types of SNP had risen to over 6000. Unfortunately, many of these studies suffer from methodological flaws derived from confirmation bias; laboratory studies which do not reflect the real world of vaping; methodologies inappropriate to the study proposal; associations presented as causal; and recommendations for policy which have little or no relation to the study outcomes. One infamous recent example of confirmation bias, resulting in a journal retraction, was a study from the University of California claiming vaping caused heart problems among those who were ex-smokers, until it was revealed these heart problems pre-dated vaping.

THR further undermined

Misleading claims of a teenage vaping epidemic, the tragic vaping deaths caused by illicit THC and the advent of COVID-19, have all been readily exploited by anti-THR actors, from ‘grassroots’ US campaigners through to national and international medical and public health agencies.

There are two overlapping sociological concepts at play. One is the role of the moral entrepreneur who seeks to impose their own standpoints on society at large, and the second is heuristics or (again) confirmation bias – whereby the public and the press don’t bother to check information, but simply accept it on the basis of their gut reaction or past experience.

Moral entrepreneurs can be individuals, religious groups or formal organisations who press for the creation or enforcement of their normative view of the world. Such individuals or groups also hold the power to generate moral panic by expressing the conviction that a threatening social evil exists that must be combated and they are not concerned with the means of achieving their desired outcome.

Moral panics

The anti-THR narrative is that the whole enterprise is a conspiracy on the part of the tobacco industry to create a new generation of nicotine ‘addicts’ to compensate for falling cigarette sales. In this narrative, little concern is shown for current smokers, whose problems are considered to be self-inflicted, leaving them two options: quit or die.

One of the many dangerous repercussions of overheated and misleading rhetoric about SNP has been the increase in the number of smokers (and also non-smokers and those living with smokers) who now believe SNP are no safer than cigarettes and may even be more dangerous.

The anti-THR activist-academics and officials are believed to be in possession of accurate information and make it available to the public and the media who in turn are unlikely to check or challenge the information. There is general antipathy towards the tobacco industry and many non-smokers will view vaping as the same as smoking, either based on existing prejudices or gut reactions and/or because they see people exhaling clouds of ‘smoke’ in public.

Anti-vaping campaign image for the WHO’s World No Tobacco Day 2020

One hand washes the other

Actions against the range of SNP and nicotine per se are conveniently conflated under a banner of ‘tobacco control’ which in most countries has public support. This has allowed activist NGOs and academics to attract substantial funding from the anti-tobacco multi-billionaire Michael Bloomberg, through Bloomberg Philanthropies (BP). Beneficiaries include US-based NGOs such as the Campaign for Tobacco Free Kids (CTFK), Vital Strategies and a UK-based reporting agency, The Bureau of Investigative Journalism, which uses Bloomberg funds to publish anti-THR stories. Bloomberg also contributed $160m to the US campaign aimed at a general ban on flavoured nicotine liquid.

Beyond the US, Bloomberg funds the International Union against Lung Disease and Tuberculosis (The Union), and in the UK, the University of Bath is funded to manage anti-THR activities through Tobacco Tactics and STOP, whose modus operandi is to launch ad hominem attacks against THR advocates. The WHO Tobacco Free Initiative also enjoys substantial financial support from Bloomberg where the funds these days appear to be deployed in persuading member states to legislate against SNP. Ironically, the beneficiaries of such a strategy will be the multinational tobacco industry for whom SNP represents less than 10 per cent of overall turnover. In fact, tobacco shares in the US and India rose in response to news of proposed bans on SNP in those countries.

Global regulatory responses

At the top of the global regulatory tree sits the WHO FCTC signed and ratified by 182 countries and the EU Tobacco Products Directive (TPD) which is concerned with many aspects of tobacco and SNP regulation within the European Union (EU).

Every two years the FCTC holds a Conference of the Parties (COP) to review the working of the FCTC, attended by signatory state delegates and the ‘approved’ nongovernmental organisations (NGOs) belonging to the Framework Convention Alliance (FCA). The next meeting (COP9) was due to be held in November 2020 but has now been postponed until 2021. This meeting excludes many organisations who support THR or who have received any funding directly or indirectly from tobacco companies.

The EU TPD is undergoing a review and its report is due out in May 2021. A significant input into the evaluation will be the report prepared by the EU Scientific Committee on Health, Environmental and Emerging Risks (SCHEER). The EU review will feed into the deliberations of the COP, where the FCTC Secretariat which administers the treaty, has already been pushing COP delegates to consider advocating more draconian SNP legislation. The likely battle ground will be over the banning of most flavours.

This attack on THR can be seen in the light of the overall failure of the WHO/FCTC and signatory states to control the smoking epidemic and the politically impossible approach of banning the sale of tobacco. Only Bhutan has banned tobacco sales but this is widely ignored. Much is made of new legislation in place in many countries, but LMIC have little of the administrative and judicial structures in place to enforce legislation. Many such countries have internal tensions between government departments, where the domestic tobacco industry is both an important export commodity and a major source of internal revenue. From a public health point of view, many LMIC will have more immediate concerns about infectious disease control than health problems caused by smoking.

Global picture remains mixed

The gradations of SNP control are complex and differ widely between countries. The GSTHR website (www.gsthr.org) has a comprehensive breakdown of the legislative regime in each country.

While control responses around the world are mixed, the emphasis is moving towards a more prohibitionist approach. There seems little doubt that anti-THR hyperbole from the US has had a global influence on policy makers and legislators.

It remains the case that 85 countries have no specific law or regulation regarding nicotine vaping products, and 75 countries regulate the sale of nicotine vaping products; 36 have bans (down from 39 in 2018).

The moves towards encouraging a flavour ban would severely damage the uptake of vaping, as the availability of flavours is an important determinant in encouraging smokers to switch and stay away from cigarettes.

Some good news too

Despite attempts by anti-THR activists to undermine its position on SNP, Public Health England reaffirmed that vaping plays an important role in helping smokers to quit and consequently, health professionals need training in the use of vaping devices. Vaping was specifically mentioned as part of the UK Department of Health target to go smoke free by 2030.

Australian government officials remain in lockstep over continued de facto prohibition. However, in January 2020, after a careful review of the evidence, the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners published new Australian Smoking Cessation Guidelines in January 2020. The Guidelines cautiously endorse vaping nicotine as a quitting aid for smokers who have been unable to quit with the available therapies, if they request help from their doctors to start vaping. This aligns with the 2018 decision by the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists to acknowledge vaping as less risky than smoking, while the Royal Australasian College of Physicians now accepts the value of vaping as part of a cessation strategy.

Judiciaries in Switzerland (2018) and Quebec (2019) have ruled against respective government restrictions on SNP, while the New Zealand government suffered its own judicial defeat in March 2018. Yet the New Zealand government (and that of the Canadian federal government if not necessarily the provinces) appears to be taking a more pragmatic and proportionate response to SNP than in many other countries. Even in the US, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has recognised the value of THR by giving marketing approval to the heated tobacco product IQOS and snus as lower risk products over smoking.

Sitting underneath the FDA decision is the substantial scientific and clinical evidence submitted by PMI (IQOS) and Swedish Match USA (snus) which should attract more attention from the scientific and public health communities. The FDA came to its landmark decisions based on this evidence so it cannot be dismissed on the grounds of its industry provenance.

THR and the right to health

The notion of non-smokers’ right to health – especially bystanders and children – underpinned tobacco control developments through the 1980s and 1990s. Those involved in the campaigns, especially in the US, saw themselves as warriors (in relation to the passive smoking hazard) battling the economic and political interests of tobacco companies. Backed by the evidence of the palpable damage caused by smoking and the increasing efforts to ban public smoking, campaigners seized the moral high ground as smokers became the new social pariahs.

The tables have turned; those whose rights now need protecting are those who want to avoid smoking and instead use safer products. Harm reduction as a social movement arose from the work of drugs and HIV activists who focused on the right to health, with nobody left behind.

However, smokers are left behind, primarily those on low incomes living in poverty and deprivation around the world, with no attractive and effective exit routes out of smoking, who smoke the most and consequently suffer most from smoking-related disease and death. The whole panoply of marginalisation, discrimination and isolation accounts for the very high smoking rates within indigenous and LGBTQ+ communities, those in prison, the homeless and those suffering mental health, drug and alcohol problems.

Women are another hidden population. Globally, fewer women smoke than men, but especially in LMIC, men are typically the main breadwinners, leaving more women at home caring for family. Losing an entire family income due to the death of the man from smoking-related disease throws women and their families into what might be an even more precarious economic situation.

Yet the ‘nobody left behind’ mantra has long been enshrined in international conventions and continues to be so. Harm reduction sits at the intersection between public health and human rights.

Article 12 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, adopted by the United Nations General Assembly on 16 December 1966, states the right of everyone to enjoy the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health. As a social justice cause, advocating for people who are often among the most disadvantaged and marginalised in society, THR merits its place as a human rights issue.

THR offers a global opportunity for one of the most dramatic public health innovations ever to tackle a non-communicable disease and at minimal cost to governments. In a time of COVID-19 when global health and public finance systems are stretched to breaking point and may not recover for some time, the imperative to drive forward with THR has never been more urgent.

The way forward

For the first time there is now a wide range of positive inducements for people to switch from smoking, rather than just disincentives. THR, through SNP, offers an unprecedented exit strategy that has been shown to be acceptable to smokers and at minimal cost to governments.

Aspirations aside, the reality is that tobacco control could only ever help to reduce harm, so the case for harm reduction has always been inherent in the mission statement for tobacco, except now there is a real-world opportunity to add enormous heft to beneficial public health outcomes.

Conclusions and recommendations

This report focuses on THR and the benefits to public and individual health of having available, affordable, appropriate and acceptable safer alternatives to combustible tobacco products. It also focuses on the rights of smokers who need the opportunity to switch from smoking and those who have chosen safer alternatives.

Conclusions

- Nearly 8 million people die from smoking-related diseases every year

- Eighty per cent of the world’s smokers live in LMIC, but have the least access to affordable SNP.

- A projected one billion people will die from smoking-related diseases by 2100.

- Smoking rates have been falling in more affluent countries for decades, but rates of decline are slowing.

- The global number of smokers has remained unchanged at 1.1 billion since the year 2000, and in some poorer countries this is set to rise due to population growth.

- The immediate way to reduce smoking-related deaths is to focus on current smokers.

- The evidence for SNP demonstrates that they are substantially safer than combustible tobacco, both for smokers and by-standers, and contribute to helping those wishing to stop smoking.

- The adoption of SNP has been consumer-driven with nil, or minimal, cost to governments.

- SNP have the potential to substantially reduce the global toll of death and disease from smoking, and to effect a global public health revolution.

- Progress in the adoption of SNP has been slow. We estimate 98 million people globally use SNP – including 68 million vapers – amounting to only nine per 100 smokers (fewer in LMIC). There is an urgent need to scale up tobacco harm reduction.

- Many well-funded national and international NGOs, public health agencies, and multi-lateral organisations incorrectly view THR as a threat rather than as an opportunity.

- Many US and US-funded organisations have manufactured panics about young people and vaping, about flavours and the outbreak of lung disease, overshadowing the real public health challenge, which is to persuade adult smokers to switch.

- The near-monopoly on international tobacco control funding by US-based foundations – philanthrocapitalism – has distorted international and national responses to smoking. Donor interests often exclude other policy options, producing a hidden but negative impact on health policies, particularly in LMIC.

- The increasingly prohibitionist emphasis risks many consequences, including that current smokers may decide not to switch, current users of SNP may go back to smoking, and the growth of unregulated and potentially unsafe products.

- There continues to be much poorly conducted research and science, which is then spun with an anti-THR message.

- The WHO’s MPOWER initiative alone will be insufficient in hastening an end to smoking – the weakest area of achievement is ‘O’ – offering help – which is also the most expensive for governments.

- Harm reduction is embedded in nearly every field of the WHO’s work except tobacco.

- By denying the role of THR, the WHO is working against the principles and practices enshrined in its own pledges for global health promotion and in international conventions relevant to the right to health, including in Article 1 (d) of the FCTC.

- Richer countries have been the main beneficiaries of THR. Many LMIC are left behind, through a combination of prohibitionist policies and the unavailability of appropriate, acceptable and affordable alternatives to combustible tobacco.

- Those most affected by tobacco control policies have been stigmatised and excluded from the policy conversation. Good public health engages affected populations. The slogan “nothing about us without us” is central to THR, as it is to any field in public health.

Recommendations

- The primary aim of tobacco control should be to offer current smokers suitable exit strategies. The current predicted toll from smoking can only be averted by hastening a switch from smoking by established smokers.

- Harm reduction should be properly defined by parties to the FCTC to sit alongside demand and supply reduction. It should be applied universally with no person, group, or community being excluded.

- The WHO must play a lead role in encouraging FCTC signatories to take a more balanced view of the potential for SNP to help encourage a switch away from combustible products. The current interpretation of Article 5.3 of the FCTC is stifling open debate on the merits of SNP. A new and inclusive approach is required, engaging with all stakeholders with no exceptions, to evaluate the merits of new technologies and products, based on scientific principles rather than ideology.

- Access to SNP should be a right for all potential beneficiaries irrespective of gender, race, social or economic circumstances.

- Consumer wellbeing should be at the centre of international planning and policy.

- The Framework Convention Alliance of NGOs should actively engage with the widest range of THR-focused NGOs, including consumer advocacy organisations.

- Companies making SNP should strive to reach the largest number of smokers globally with appropriate and affordable products.

- The role of government should be to hasten the switch from smoking, rather than to place obstacles in the way of those who wish to use SNP.

- No action should be taken which has the consequence of favouring smoking over SNP, such as making SNP harder to obtain and use than cigarettes, or through unfavourable pricing (e.g. through taxes).

- All those in positions to formulate policy on SNP should take account of the body of current evidence, rather than opting for off-the-shelf recommendations from multi-lateral and philanthropic organisations.

- Governments should ensure consumer safety in relation to SNP, based on safety standards available through international, regional and national bodies.

- Smokers have the right to evidence-based information about the potential benefits of switching to SNP.

- SNP should be controlled and regulated as consumer products, and consumers need to be assured of the quality of the products they are using.

- Having a choice of flavours in SNP is an important aspect of the decision to switch away from smoking and to avoid relapse. Banning flavours is counter-productive to positive public health outcomes.

- There is no identified risk of ‘passive vaping’ to bystanders. Public health communication should explain that vaping is not smoking, and ultimately the decision to control vaping in particular locations should be left to individual organisations and businesses, rather than through blanket prohibition by government bodies.

The two years since the last edition of this report has been a very difficult time for THR.

The estimated 1.1 billion smokers around the world deserve a better deal and better options. We need to hasten the demise of combustibles and encourage the use of safer non-combustible ways of using nicotine. Evidence from several countries shows that the availability of SNP helps people to switch from smoking.

Globally, progress is slow and those using SNP are still a small fraction of those who smoke. Vaping products have only been on the market for about 12 years and HTP much less, although snus use goes back centuries. Historically, changes in nicotine consumption take some decades. The last disruptive innovation was the invention of the tobacco rolling machine back in the 1880s, but it took around 60 years for the machine-rolled cigarette to oust most other forms of tobacco use in richer countries.

However, we can’t wait 60 years. We know that SNP are just that – safer than getting nicotine by burning tobacco. We know that people want to use these products. We have proof from many countries that THR works.

The obstacles are rich foundations with a myopic view of tobacco control, and international organisations wedded to a narrow view of what can be done. There’s too much fear, hatred and vested interest in this field. These organisations are rapidly finding themselves on the wrong side of history. There needs to be much more ambition about what can be done, and a healthy dose of compassion.

During the 1980s, public health policies broadened in scope beyond the control of infectious diseases, to wider considerations of prevention through health promotion. In November 1986, the WHO convened the First International Conference on Health Promotion, held in Ottawa, Canada. From that emerged a five-page document called the Ottawa Charter, which defined health promotion,

“as the process of enabling people to increase control over, and to improve, their health”.

It went on to highlight that,

“Health promotion focuses on achieving equity in health. Health promotion action aims at reducing differences in current health status and ensuring equal opportunities and resources…People cannot achieve their fullest health potential unless they are able to take control of those things which determine their health”.

Pledges made by the participants in the Conference included:

- “to counteract the pressures towards harmful products”.

- “to respond to the health gap within and between societies, and to tackle the inequities in health produced by the rules and practices of these societies”.

- “to acknowledge people as the main health resource, to support and enable them to keep themselves, their families and friends healthy”.

Tobacco harm reduction is good public health and health promotion, starting with the people who matter: smokers and those who have chosen alternatives. It’s change driven from community level upwards – because it’s people who do harm reduction, not experts.

About the report

This is the second edition of the Global State of Tobacco Harm Reduction report first published in 2018. The report takes its inspiration from the Global State of Harm Reduction published by Harm Reduction International (HRI). Also published biennially, the HRI report tracks progress in the introduction of drug harm reduction interventions such as opioid substitute therapy, needle exchange and overdose prevention facilities, also known as drug consumption rooms.

In the same vein, this report maps progress (or otherwise) in global, regional and national change in the availability and use of SNP, the changing regulatory response together with the latest evidence on safer nicotine products and health. We focus too on those the report calls ‘the left behind’ – groups and communities all over the world who smoke at much higher levels than the rest of society to cope with a multiplicity of economic, social and personal problems. As the environment for THR has grown ever more toxic since our last report, we have turned our attention this time to the mechanisms of the well-orchestrated and well-funded global campaigning driving an increasingly prohibitionist response to SNP.

The information in the report will be useful to policymakers, policy analysts, consumers, legislators, civil society and multi-lateral organisations, media, public health workers, academics and clinicians as well as manufacturers and distributors.

Readers are encouraged to refer back to the previous report for some of the background information omitted this time around. Go to: www.gsthr.org/report/fullreport- online

Terminology

There are several terms for tobacco harm reduction (THR) products including alternative nicotine products, new or novel nicotine products, modified or reduced risk products, less harmful, lower risk or less risky products and electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS).

This report uses the term safer nicotine products (SNP) as a collective expression for vaping, heated tobacco devices and Swedish style snus and some other safer forms of smokeless tobacco. We justify this on the basis that the evidence demonstrates these products present a lower risk than combustible tobacco products by a substantial margin.

Beyond issues of semantic convenience is the issue of technical accuracy. Unlike the previous report, unless quoting other sources, we are not using the term ‘e-cigarette’, instead using vaping devices or products. While ‘e-cigarette’ is a term in common use and readily understood, it is too easily confused with the idea of smoking a cigarette; many misleading public health communications refer to the dangers of ‘smoking e-cigarettes’. The most important innovation of vaping devices is they specifically do not emit dangerous toxic smoke, but substantially safer vapour.

Following the same principle, we have decided on the term vitamin E-related lung injury (VITERLI) rather than the more commonly understood EVALI (E-cigarette or Vaping Lung Injury), which incorrectly links the outbreak of lung injury to vaping nicotine liquid. The report also now refers to heated tobacco devices or products (HTP) as opposed to heat-not-burn devices or products.

Data limitations

All efforts have been made to present the most up to date and coherent data across all the sections of this report. However, there are numerous gaps and caveats to be highlighted:

- There is a dearth of information on the prevalence of use of SNP, and in countries that conduct surveys there have been few updates since 2018.

- Many countries do not have adequate information on smoking prevalence and health outcomes.

- Much consumer, market and product data does not appear in the public domain – it is not released by companies as it is deemed commercially sensitive, and is often only available at high cost from market analysis companies.

The GSTHR website

Back in 2018, when the first GSTHR was published, we also launched the world’s first website dedicated to providing a global overview of tobacco harm reduction as it relates to the use of safer nicotine products. Since then www.gsthr.org has been substantially improved combining original features with a new suite of options.

Overall, all the narrative and data on the website has been configured to be accessible on computers and mobile devices.

A key feature of the upgraded website are 200+ country profiles which provide data on smoking prevalence and mortality alongside SNP data highlighting, for example all the regulations and controls appertaining to SNP in that country. Moreover, users can call up on-screen comparison data for different countries – and unlike other websites providing data on smoking which can be two years or more out of date, the GSTHR team constantly monitor global data and update the site in real time while also enabling data to be compared over time. Each profile also contains current in-country news about THR developments.

The site is configured to allow users to create maps and charts from the data while all the illustrative material (excluding photos) is freely available to be downloaded for use in conference and seminar presentations and for research and policy documents, for example.

Readers are encouraged to sign up to the website to receive notifications of the latest developments.

Use and quotation of material from this report

Copyright in original material in Burning Issues: The Global State of Tobacco Harm Reduction 2020 resides with Knowledge-Action-Change, except graphs and text where other sources are acknowledged. Readers of the report and the website are free to reproduce material, subject to fair usage, without first acquiring permission of the copyright holder and subject to acknowledgement using the citation: Burning Issues: Global State of Tobacco Harm Reduction 2020. London: Knowledge-Action- Change, 2020.

Forewords

Samrat Chowdhery

President of the International Network of Nicotine Consumer Organisations

Nearly two decades into the WHO-led war on tobacco, death rates from smoking are on the increase in some countries, highlighting the need to address gaps in implementation and approach. Yet, as this report reveals, we are witnessing further derailment, propped up by a few private parties with a prohibitionist worldview and deep pockets to see it through. Instead of a course correction, a new front has been opened against harm reduction principles that were borne out of the earlier failed wars against substance abuse.

Caught in the crossfire are over a billion tobacco users who, despite paying the highest taxes and suffering the gravest consequences, find themselves without a voice, a platform for redressal, or support. Offering help to consumers remains the most underimplemented of WHO’s tobacco control measures, while the framing of the tobacco war in the broadest terms denies them representation under the pretext of excluding the tobacco industry.

That over 80 per cent of the users are in low- and middle-income countries with meagre means to deal with tobacco-related consequences – the largest vulnerable group on the planet by any measure – the focus ought to be unwaveringly on harm prevention by allowing them to exercise the choice of avoiding death and disease by switching to affordable and accessible risk-reduced alternatives should they feel unwilling or unable to quit.

In fact, the opposite is happening. Since the first edition of this global report in 2018, the climate for tobacco harm reduction has worsened, its legitimacy questioned on weak scientific grounds, and progress stunted with a moral panic that diverts from the laudable goal of limiting tobacco death and disease to actively limiting access to safer products – through bans in low- and middle-income countries and restrictions on flavours, a key switching aid, in developed nations.

The silver lining is that millions of smokers have transitioned to lower-risk products in little over a decade, which puts to rest doubts about their effectiveness and also indicates the willingness of users to take proactive measures to protect their health. But as the report notes, this is still a small step given the large number of users globally, and continued demonisation of tobacco harm reduction alternatives could well turn the tide against them.

This report is as much a record of the adoption of harm reduction policies across the globe as it is a snapshot of the efforts to oppose them.

Fiona Patten

Leader of the Reason Party, and a Member of the Victorian Legislative Council for the Northern Metropolitan Region, Australia

Facts matter and when it comes to harm reduction measures aimed fairly and squarely at fighting the global disaster that is preventable deaths from smoking, they matter more than ever.

This report maps the progress that has been made around the world in the availability of safer nicotine products (SNP), the regulatory response and the latest scientific and clinical data regarding the efficacy of alternatives to combustible cigarettes.

Incredibly there are people and organisations in the community that seek to peddle ‘alternative facts’ under the policy banner of tobacco regulation. Their misguided efforts ignore the basic right of everyone to health care options – and that includes those across our society who, for a variety of reasons, have engaged in risky behaviours. It’s not for us to judge. The job of governments and health organisations around the world is simple, reduce health risks and improve the overall health of citizens.

Australia was once a leader in harm reduction as well as effective tobacco regulation, but we are desperately falling behind because we are ignoring the facts. Our stagnant smoking rates are evidence of this. Government support for clean needles and methadone is universal here in Australia but these same governments prohibit products proven to reduce the harms of nicotine addiction. Sadly, they have chosen to ignore the facts. Why?

My theory is that nicotine addiction is considered more of a personal choice than, say, an addiction to heroin. Somehow you should have the willpower to just say no to smoking and maybe SNPs make it look easy. Quitting should be hard, they believe. It should be painful. This attitude ignores the economic savings that tobacco harm reduction delivers, ignores the research and ignores the evidence. It ignores the facts and it literally kills people. On top of this our anti-cancer councils want to ban vaping as a SNP while being funded by the nation’s largest tobacco retailers. Go figure.

I commend this report and live in hope that more countries including Australia will appear in a more positive light in the next report.

Ethan Nadelmann

Founder and Former Executive Director (2000–2017) of the Drug Policy Alliance

It’s a shame that a report such as this, grounded as it is in a deep regard for science, health and human rights, must be produced by a non-governmental organisation. But just as Harm Reduction International realised years ago that it must take on the task of producing its Global State of Harm Reduction report because the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime and other international and governmental organisations were not willing to produce such a report, so this document reflects the failure of WHO, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and other governmental agencies to address honestly the evidence on tobacco harm reduction.

The global war on (illicit) drugs was driven, and is driven still, by a combination of ignorance, fear, prejudice and profit. The problem was not just that public and political opinion so often diverged from scientific and other empirical evidence but also that government agencies, powerful philanthropies and even scientists themselves were blinded and corrupted by abstinence ideologies, anti-drug propaganda and the politicisation of funding for research and treatment. Even many liberal politicians abandoned their commitments to science, compassion and human rights, and scientists dependent on government funding developed political blinders that evolved into intellectual blinders. The results, most now concede, were disastrous not just for those who use drugs illicitly but for societies at large.

Harm reduction must play at least as central a role in tobacco control as it increasingly does in illicit drug control if the number of people dying from tobacco-related illnesses is to decline dramatically. But public policies are moving more backwards than forwards of late, driven in part by governmental agencies and philanthropic advocacy organisations that shamelessly deceive the public. Nowhere is this more evident than in public opinion surveys showing significant increases in the number of people who incorrectly believe that e-cigarettes and other harm reduction devices equal or exceed the dangers of combustible cigarettes.

No one should trust Big Tobacco, given not just their notorious history but also the fact that their bottom line will always prioritise profit over health given the demands of market competition and shareholder interests. The tobacco control advocates who have fought most valiantly against Big Tobacco are now divided. On one side are those, now amply funded by governments and wealthy philanthropists, who seek to transform a science-based health campaign to reduce cigarette smoking into a poorly conceived campaign to demonise virtually all nicotine products, no matter how much less dangerous than combustible products. On the other are those truly committed to harm reduction principles and the overriding objective of reducing the harms associated with both tobacco use and tobacco control policies. This report honours them.

Abbreviations and acronyms

AFNOR – Association Française de Normalisation

ANSA – EU Agency Network for Scientific Advice

ASH – Action on Smoking and Health (UK)

BMGF – Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation

BP – Bloomberg Philanthropies

BSI – British Standards Institute

CBD – Cannabidiol

CDC – Center for Disease Control and Prevention (US)

CDER – Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (US)

CEN – European Committee for Standardisation

COP – Conference of the Parties – WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control

COT – Committee on Toxicity, Carcinogenicity and Mutagenicity of Chemicals in Food,

Consumer Products and the Environment (UK)

CTFK – Campaign for Tobacco Free Kids (US)

CTP – Center for Tobacco Products (US)

DG SANTE – Directorate-General for Health and Food Safety (EU)

DOTS – Directly-observed therapy short course

ENDS – Electronic nicotine delivery systems

ERS – European Respiratory Society

ESTOC – European Smokeless Tobacco Council

EVALI – E-cigarette or vaping product use-associated lung injury

FCTC – WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control

FDA – US Food and Drug Administration

GBD – Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries and Risk Factor Study

GDP – Gross Domestic Product

GSTHR – The Global State of Tobacco Harm Reduction

HNB – Heat-not-burn

HSS – Department of Health and Human Services (US)

HTP – Heated tobacco products

HPHCs – Harmful and potentially harmful constituents

IARC – International Agency for Research on Cancer

ISO – International Organisation for Standardisation

LMIC – Low and middle-income countries

MHRA – Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (UK)

MPOWER – Monitoring-Protect-Offer-Warn-Enforce-Raise (taxes)

MRTPA – Modified Risk Tobacco Product Application

MSA – Master Settlement Agreement

NCCDPHP – National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (US)

NCD – Non-communicable diseases

NGO – Non-governmental organisation

NIH – National Institutes of Health (US)

NRT – Nicotine replacement therapy

NYCHD – New York City Health Department

NYU – New York University

ONDIEH – Office of Non-Communicable Disease, Injury and Environmental Health (US)

OSI – Open Society Institute

ONS – Office for National Statistics (UK)

OSH – Office for Smoking and Health (US)

PAHs – Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons

PHA – Public Health Association (New Zealand)

PHE – Public Health England (UK)

PMTA – Pre-Market Tobacco Application (US)

RCP – Royal College of Physicians (UK)

RDTA – Rebuildable dripping tank atomiser

RWJF – Robert Wood Johnson Foundation

SCENIHR – Scientific Committee on Emerging and Newly Identified Health Risks (EU)

SCHEER – Scientific Committee on Health, Environmental and Emerging Risks (EU)

SEATCA – Southeast Asia Tobacco Control Alliance

SITRPS – Schroeder Institute for Tobacco Research and Policy Studies

SLAM – South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust (UK)

SNP – Safer nicotine products

ST – Smokeless tobacco

STOP – STOP Tobacco Organisations and Products

STP – Smokeless tobacco products

TFI – WHO Tobacco Free Initiative

THC – Tetrahydrocannabinol

THR – Tobacco harm reduction

TI – Truth Initiative

TobRegNet – WHO Study Group on Tobacco Product Regulation

TPD – Tobacco Products Directive (EU)

TPSAC – Tobacco Products Scientific Advisory Committee (US)

TSNAs – Tobacco-specific nitrosamines

TT – Tobacco Tactics

VITERLI – Vitamin E-related lung injury

VS – Vital Strategies

WHO – World Health Organization

WLF – World Lung Foundation