Market forces: products and consumers

“Nothing is so painful to the human mind as a great and sudden change.”

Mary Shelley

Joseph Schumpeter, one of the most influential economists of the 20th century, is credited with popularising the idea of ‘creative destruction’ in economics. This refers to a process of “industrial mutation that incessantly revolutionises the economic structure from within, incessantly destroying the old one, incessantly creating a new one”. Since Schumpeter wrote this in 1942 for his book Capitalism, socialism and democracy, the pace of technological change has increased significantly, making it ever harder for large well-established companies to keep pace.

In their pioneering 1995 article in the Harvard Business Review, Joseph Bower and Clayton Christensen wrote that “one of the most consistent patterns in business is the failure of leading companies to stay at the top of their industries when technologies or markets change. Goodyear and Firestone entered the radial-tyre market quite late. Xerox let Canon create the small-copier market. Bucyrus-Erie allowed Caterpillar and Deere to take over the mechanical excavator market. Sears gave way to Wal-Mart.” 29

Bower and Clayton go into more detail on how IBM missed out on the personal computer market. Had they been writing more recently, they might have added Kodak’s belief they had nothing to fear from digital cameras, and that Microsoft was way behind the curve on the significance of the internet.

The mistake many companies make is to stay too close to their mainstream customers, who may have no need for innovation. So Xerox corporate customers had no need for table top photocopiers, any more than IBM’s corporate and government mainframe customers saw any need for desktop computers.

SNP have been similarly disruptive. In their 2013 Annual Report, Goldman Sachs defined creative disruption as a process that is “driven by product or business model innovation – often abetted by technology – that results in a superior value offering for consumers, be it higher performance, greater convenience or lower cost.” 30 Goldman Sachs believed that vaping products had “the potential to transform the tobacco industry.” Indeed, as far back as 1958 and as concerns about cigarette safety grew, one tobacco executive remarked that anybody who came up with the ‘safe’ cigarette would dominate the market.31

In 2013…Goldman Sachs…believed that vaping products had “the potential to transform the tobacco industry”

Referring to the work of Bower and Clayton, Danish business expert Jacob Hasselbalch makes a distinction between disruptive technology and disruptive innovation. He defines disruptive technologies as those which present much better or faster ways of accomplishing a goal. Disruptive innovation, he argues, makes use of new technologies to present end-users with a product or service superior to those currently existing. From this, new markets are created.32

Following centuries of tobacco chewing and pipe smoking, the invention of the cigarette in the 19th century was a disruptive technology. Invented by James Bonsack in 1880, the disruptive innovation was the cigarette rolling machine with a production of 200 cigarettes per minute, replacing a workforce of up to fifty people rolling by hand. Over a ten-hour shift, Bonsack’s machine was churning out 700,000 cigarettes a day, laying the ground for the modern tobacco industry.33

As is so often the case with modern day business disruption, the revolution in making nicotine consumption dramatically safer came from outside the tobacco industry. There were some attempts by the industry to produce a non-combustible nicotine product. All failed, until a Chinese pharmacist Hon Lik patented the first modern e-cigarette in 2003.

An American patent attorney, Mark Weiss, brought Hon Lik’s product, the Ruyan, into the US in 2006 and founded NJOY, one of the first companies to manufacture and sell vaping products in the US. Their King product was a classic e-cigarette, disposable with a faux white paper wrapping, a filter and red ‘ember’ which lit up when drawn on. 34

The cigarette rolling machine was a disruptive innovation: one machine churned out 700,000 cigarettes a day, leading to the modern tobacco industry.

For the next five years, the industry grew through word of mouth and the development of online sales. Then in 2012, Lorillard paid an estimated $135m for the main NJOY rival called blu, launched in 2009 by Australian entrepreneur Jason Healy. The vaping business had soared in value over a short space of time, but the entry of major tobacco companies such as Lorillard, Reynolds, and Altria into the fray was a game-changer. These companies had the traditional distribution outlets – and so were able to place the new products right where the smokers were. However, the distribution power of these traditional tobacco companies did not necessarily guarantee successful entry into a market driven by technology and innovation.

In Europe a British businessman, Greg Carson, is credited with introducing what he called the ‘Electro Fag’ in 2005. Interviewed by the Daily Mail in July 2007, Carson said he came across the device on the internet and went to China to investigate: “At first, I was highly sceptical, but I took a trip out there to see it with my own eyes. As a non-smoker it was difficult to form an opinion, but I brought some samples back with me. The reaction has been phenomenal. The product might look simple, but the technology is astonishing.” In the UK, the indoor smoking ban came into force on 1st July 2007; Carson imported 1,500 of what the Daily Mail called ‘fake cigarettes’ to beat the ban.35

“The product might look simple, but the technology is astonishing.”

The article (dated 7 July 2007) described the new device as follows:

“The new Electronik cigarette lights up, appears to blow smoke and satisfies the most desperate nicotine craving.”

It included an account from Anna, a smoker, who „roadtested the new invention on a night out in London.”

Settling myself into a pub off Kensington High Street, I bought myself a glass of wine and took a drag. Nothing happened, so I tried again. This time, I definitely tasted a faint whiff of raspberry-flavoured air. [...] It tasted quite nice, but nothing like a cigarette.

In 2006, Professor Bernhard-Michael Mayer, a toxicologist at the Karl-Franzens University in Graz, Austria, was approached by Renatus Derler:

“He came to my office and showed me a small box lettered in Chinese. It turned out to contain a cigar-type electronic cigarette. Rene discovered this device (made by Ruyan) in China and managed to get the exclusive right for marketing in Europe. [He took out a patent in January 2007]. He asked me for a written expert opinion on the toxicology and potential usefulness of this device for smoking cessation. At that time, I was a heavy smoker and was enthusiastic after the first draw. No surprise, as I had selected the ‘strong’ variant, which contained 60 mg/ml nicotine. I provided him an overwhelmingly positive report for the Austrian authorities and predicted this device would eradicate smoking within the next 15 years.”36

But even before Derler went to see Professor Mayer, the product was in circulation. In April 2005, a Philip Morris lawyer staying in an Italian hotel saw a TV advert claiming this product “tasted like Marlboro”.

From the point of view of the history of vaping and tobacco harm reduction, it is interesting that Professor Mayer’s report concluded as far back as 2006 that, “since there is no combustion process, …the health risk is therefore much lower than when tobacco products are consumed.”37

That small report about an unknown device was the harbinger of a revolution in ways to consume nicotine which inaugurated a global THR movement.

SNP products

Vaping devices

Rapid innovation continues in new nicotine delivery systems. In the 2018 GSTHR report, we went into some detail about the various types of SNP. 38 With respect to vaping devices, the most notable change is the rising popularity of pod systems of various types which offer the portability of the original ‘e-cigarette’ with the power of larger so-called box mods.

Devices have otherwise remained much the same save for various small refinements to make them more user friendly – top fill tanks are now common, for example, where more awkward bottom fills were previously the norm. Sub-ohming (where large clouds are produced using lots of power) is now less popular as the more demure mouth to lung (MTL) vaping style has seen a comeback, demonstrated by the increasing number of MTL tanks on the market, many of which now have a rebuildable option for people who wish to make their own coils. The global regulatory environment has been responsible for the demise of many independent e-liquid producers and there is also less variety in hardware production, as most of the devices on the market are produced by a handful of manufacturers in Shenzhen, China.39

While just another vaping device, in just a few years JUUL has become America’s most popular and its most controversial device, so much so that the term ‘juuling’ has become commonplace alongside ‘vaping’. JUUL is a discreet device and can be charged via a USB connection. JUUL uses nicotine salts rather than freebase nicotine liquid, which allows for higher and speedier levels of nicotine delivery similar to that of a combustible cigarette, without the accompanying throat irritation.40 The nicotine hit and JUUL’s compact design account for its popularity.

Fuelled by a major tobacco company Altria buying a 35 per cent stake in JUUL, the company faced substantial criticism for a marketing campaign aimed at young adults. This prompted claims by anti-vaping groups that JUUL single-handedly created a vaping ‘epidemic’ among teenagers. As of February 2020, JUUL in America lodged a Pre-Market Tobacco Product Application with the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for its standard product and for one which can only be activated through an appbased, government-verified age identification system.

Heated tobacco products (HTP)

Like vaping devices, there is a back story of industry attempts to bring a successful heated tobacco device to market. Vaping technology was relatively simple, allowing several small start-ups to enter the market. By contrast, the cost of HTP development meant the field has been left to the major tobacco companies who have had the resources necessary to pioneer this technology. IQOS (PMI), Ploom Tech (JTI), glo (BAT) and Pulze (Imperial) were the first to market. However, new players are now joining the field, such as US companies 3T and Firefly, alongside China Tobacco with their Mok device and Korea Tobacco’s lil. The number of countries in which HTP products are sold has increased from 37 (in our 2018 report) to 54.

The number of countries in which HTP products

are sold has increased from

37

(in our 2018 report) to

54

Smokeless tobacco

Many parts of the world have versions of smokeless tobacco, which can be chewed, inhaled nasally, or placed under the lip.

Tobacco chewing became widespread in the main tobacco growing areas of the American south from the mid-19th century onwards and is still in vogue among some young males in the southern states, although its popularity was already on the wane before the Second World War.

Dipping tobacco is a type of finely ground or shredded, moistened smokeless tobacco product. It is used by placing a lump, pinch, or ‘dip’ of tobacco between the lip and the gum. This evolved into modern day moist snuff, with Copenhagen introduced in 1822, and Skoal introduced in the US in 1934, betraying the Scandinavian roots of this type of smokeless, oral tobacco product. Dipping tobacco is typically flavoured, most commonly with mint and wintergreen, but also grape, cherry, apple, orange, lemon/ citrus, peach and watermelon.

The largest markets for US-type smokeless tobacco and snus (excluding Asian smokeless) in dollar terms are the US, Sweden and Norway.

Snus

Swedish snus is a moist smokeless tobacco product, made from ground tobacco leaves and food-approved additives. Among all the smokeless tobacco products, snus has captured most attention, because of its success in reducing the prevalence of lung cancer and other tobacco-related diseases in Sweden.41 Today, the dominant snus brands come in small teabag-like sachets which users insert in the mouth, often under the upper lip.

Snus production involves processes which decrease both the microbial activity and level of carcinogenic tobacco-specific nitrosamines in the final product. Production changes introduced over the past few decades by the major manufacturers have resulted in reducing levels of unwanted substances in Swedish snus still further.

The nicotine content of snus varies between brands, with the most common strength being 8 mg of nicotine per gram of tobacco while stronger varieties may contain up to 22 mg of nicotine per gram of tobacco.

Non-tobacco nicotine pouches

With vaping products coming under increasing political and legislative threat in many countries, a new product category is emerging with several major tobacco companies now selling ‘tobacco-free’ nicotine pouches. These products are sold as pre-portioned pouches similar to snus, but instead of containing tobacco leaf, they are filled with white nicotine-containing powder and come in a variety of flavours with a nicotine content ranging from 2–7mg. The pouches are placed between the lip and gum and require no spitting or refrigeration.

There are various brands currently on the market in different countries. Dryft is owned by Kretek International and sold in the US. British American Tobacco market Lyft in the UK, Sweden and Kenya. The nicotine content for Lyft is 4 and 6 mg. In 2019, British American Tobacco started selling nicotine pouches in Kenya. In Sweden, Switzerland and the UK, consumers can buy Nordic Spirit sold by Japan Tobacco International. Altria purchased 80% of the On! nicotine pouch company, the product being sold in Sweden, Japan and the US. The R.J Reynolds Vapor Company produce Velo, Imperial Tobacco have their own brand Zone X sold in the UK, while Swedish Match have Zyn, sold in Europe and the US.

THR and smokeless products

Beyond the safer products listed above, especially in India and East Asia, there are varieties of smokeless products containing other, potentially dangerous compounds in addition to tobacco.

With different names such as paan and gutkha, the betel/araca nut combination is found right across the region, in India, Pakistan, Indonesia, the Philippines, Taiwan, Myanmar, Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam and also reaching these communities the world over. With or without tobacco, these forms of smokeless tobacco products present a risk of oral and other cancers. This could be significantly reduced, if not obviated, by a switch to snus-style pouches.

SNP: global markets and consumers

So, what has been the impact of these new and longer established products in terms of consumer uptake of SNP?

Establishing accurate data for markets in SNP isn’t easy. Much of the information that is collected is retained by companies manufacturing these products, online sellers and by market research analysts. The information is not freely available in the public domain. However, this information is important for public health analysis and should be shared.

The global market in nicotine

The global nicotine market was estimated to be worth approximately $785 billion in 2017, including all tobacco products, vapour products and NRT products. Cigarettes make up 89 per cent of the nicotine market by sales value, and in 2017, all combustible products together (cigarettes, cigars and cigarillos, and rolling tobacco) comprise 96 per cent of the nicotine market by retail sales value.42

The six largest tobacco companies dominate the nicotine market with China National Tobacco Corporation being the largest producer in 2017 having 38 per cent of the volume share (calculated by cigarette stick equivalents) followed by British American Tobacco and Philip Morris International (each 13 per cent), Japan Tobacco Inc (9 per cent), Imperial brands (4 per cent) and Altria Group Inc (3 per cent).

Non-combustible products were globally still a small part of the nicotine market in 2017 – at about 4 per cent. Smokeless tobacco products comprised around 1.6 per cent, vaping systems 1.5 per cent, HTP 0.8 per cent and NRT 0.3 per cent.

Cigarette sales volumes are declining at about 2 per cent a year. By comparison, vapour products have shown the biggest increases in recent years although from a very small base.

96

per cent

the percentage of nicotine sold as combustible products (cigarettes, cigars,

cigarillos, rolling tobacco). The dirtiest nicotine delivery system

– cigarettes – dominates at 89 per cent.

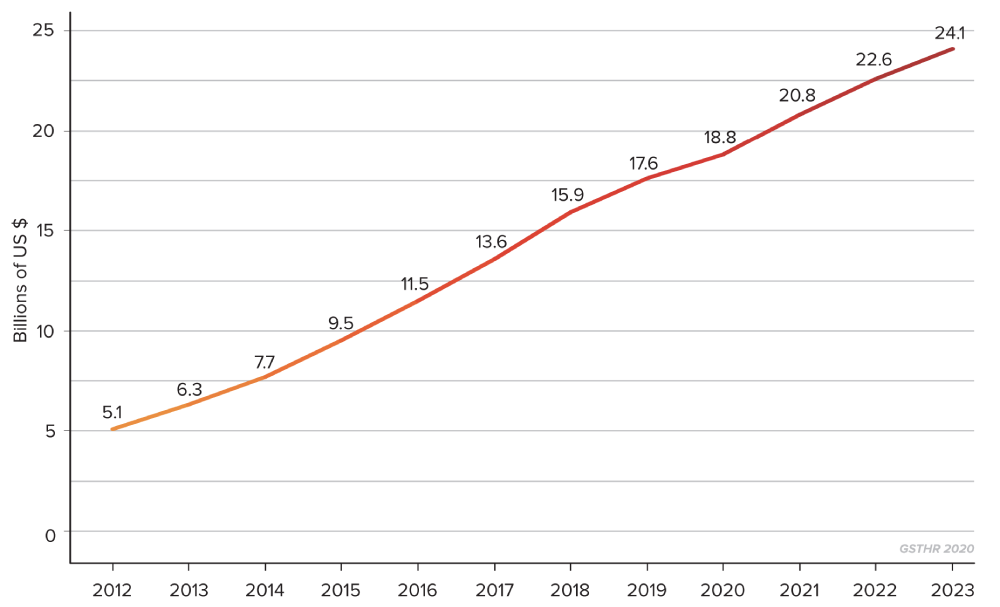

Globally, the value of the vaping market has continued to grow since our 2018 report and is projected to grow further. The chart from Statista43 shows the value of the e-cigarette market at around $19bn and its steady projected growth from 2012 through to 2023. Market values are commonly quoted by market research companies, but because they are based on retail sales by large manufacturers and through major commercial outlets, they underestimate sales from smaller retailers, specialist vape shops and online sellers.

The highest number of vapers live in the United States, China, Russian Federation. United Kingdom, France, Japan, Germany and Mexico.

The US is the world’s biggest vaping market. Vaping products account for somewhere between 5-10 per cent of the tobacco market (excluding sales from smaller outlets noted above) and for about 70 per cent of the global market in new pod mod systems.

4

per cent

the percentage of nicotine by value sold in 2017 as non-combustible

products – smokeless tobacco, vapes, heated tobacco, NRT.

Worldwide revenue in the e-cigarette market

The share of the vaping market owned by tobacco companies remains small. Tobacco companies are estimated to have less than 20 per cent market share of the global vaping market. In France, Italy, Germany and most other markets it is less than 10 per cent; in the USA and Russia it is around 20 per cent, and estimated to be highest in the UK (33 per cent) and Poland at around 50 per cent. In China, it is zero per cent. 44

Japan dominates the market in HTP with smaller but growing markets in over 50 other countries.

In the light of a more adversarial atmosphere in the US towards vaping products and eager not to endure a Kodak moment, all the major tobacco companies have now brought non-tobacco nicotine products to market.

Tobacco companies have less than 20 per cent share

of the global vaping market.

Most market estimates predict continued growth but there are concerns about the impact of misinformation about teen vaping, scares about vaping-related lung injury and deaths, COVID-19 and the increasingly belligerent attitude towards SNP among legislators.

So, how many people are using these products?

Global use of SNP

There is no clear way to translate market data into numbers of people globally using SNP.

Companies are interested in market numbers and value. Market data can report trends in dollar values and units sold. But from a public health perspective what is important is the numbers of people using different SNP, how this compares with smoking, and trends in both smoking and SNP use over time. This information can only be gained from population surveys. Given the health, economic and political significance of SNP, it is surprising how little information there is concerning the number of people using them. The dearth of data creates problems for those charged with making regulatory decisions and undertaking public health analysis.

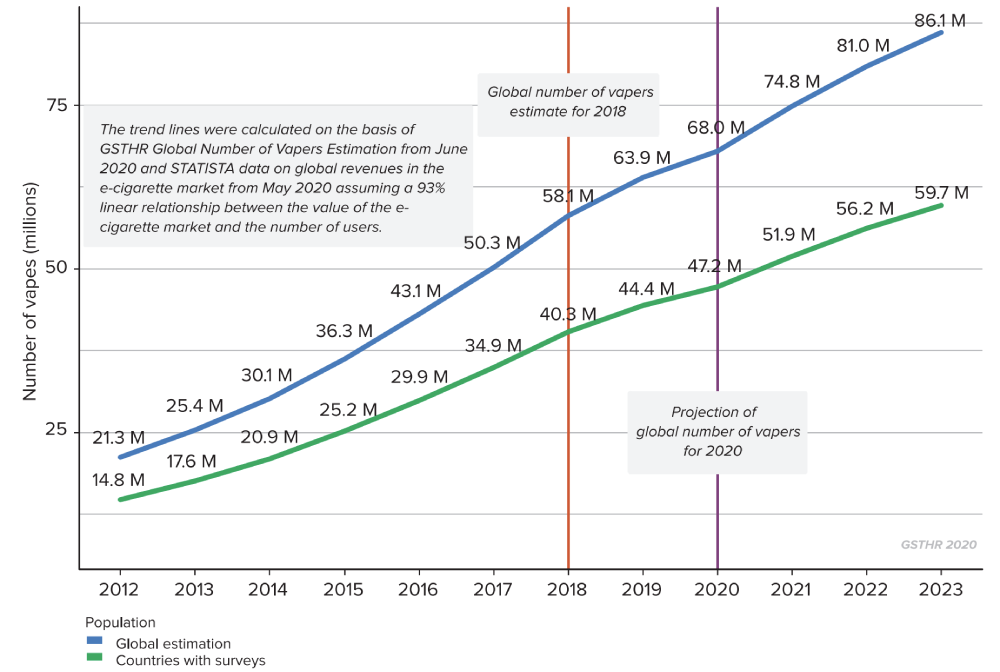

The market analysis company Euromonitor estimated in 2011 that 7 million people were regular dual or sole users of vaping products around the world. That estimate rose to 35 million in 2016 and 40 million in 2018 and was predicted to rise to around 55 million by 2021.45

The GSTHR estimate of the number of nicotine vapers globally

We have made the first attempt to estimate the global prevalence of vaping. This has been based on national prevalence surveys where available. Data were available for various years between 2011 and 2019 for 49 countries.

Estimated trends in the worldwide number of vapers

E-Cigarettes – worldwide | Statista Market Forecast (adjusted for expected impact of COVID-19). (2020, May). Statista. https://www.statista.com/ outlook/50040000/100/e-cigarettes/worldwide

68

million

the estimated number of vapers globally.

Where national data were unavailable, we have used an accepted epidemiological method of estimating country data of assumed similarity with other countries in the same region for which data points are available. This methodology is commonly used for estimating health status in the absence of national surveys; it may be less reliable for estimating consumer behaviour. We adjusted by World Bank income classifications. We have also adjusted figures according to the legal status of vaping products, adjusting prevalence downwards for states where these are not legal. Given that the vaping market has increased since many of the surveys were conducted, we made a market value correction. We further undertook a reality check with key correspondents for selected countries, especially for those with high estimated numbers. Details of our methods can be found in the Annex (page 151).

Based on this approach we estimate that as of 2020 there were 68 million vapers globally. A lower estimate, based only on the 49 countries for which survey data are available, is over 47 million.

Estimated number of HTP users globally

It is harder to estimate the number of HTP users given the paucity of national data. We have therefore had to rely on manufacturers estimates.

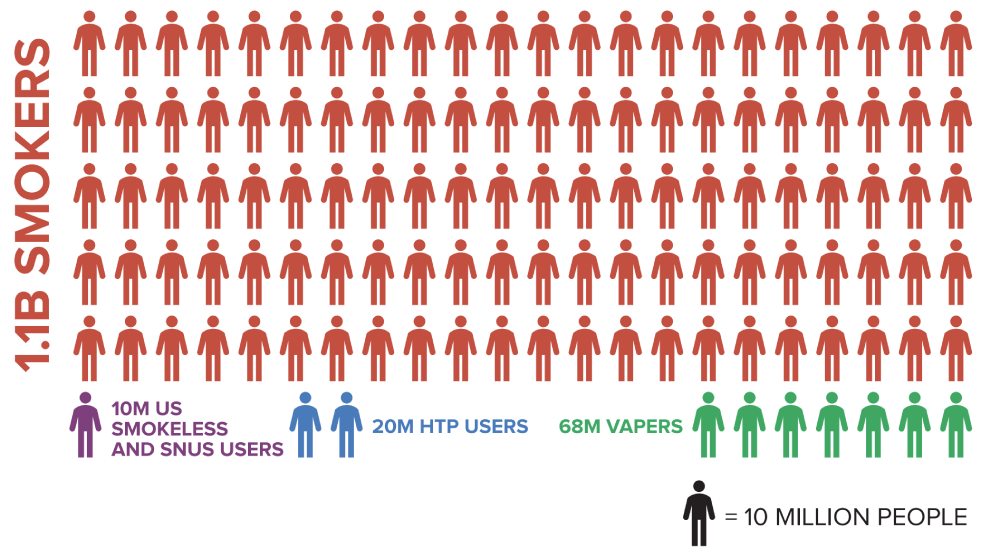

The April 2020 investor report from Philip Morris International46 indicates 14.6 million IQOS users, of whom approximately 10 million are “converted” users, defined as people that used IQOS for over 95 per cent of their daily tobacco consumption over the past seven days. Market analyst estimates suggest 10 million HTP users in Japan and 20-25 million globally.47

We have been unable to confirm these estimates from independent sources. Given that there may well be overlap in consumer use of devices from different companies, a conservative estimate is that there may be 20 million users of HTP. (As a reality check, Euromonitor estimates of the vaping market in our first report suggested HTP users constituted about one third the number of vapers48).

Estimated number of US smokeless users and snus users

The US National Survey on Drug Use and Health estimates that there are around eight million consumers of smokeless tobacco in the USA,49 meaning chewing tobacco or snuff on one or more of the previous 30 days. Dissolvable tobacco, dip, and US snus were not measured.50 Manufacturer data indicate 1 million snus users in Sweden.51 Market analyst estimates are that there are 1.6 million snus users in the US, Sweden and Norway.52 Given the paucity of global data and different definitions of ‘use’ we take a conservative ‘guesstimate’ of 10 million US smokeless and snus users globally.

GSTHR estimate of the numbers globally using all safer nicotine products

We estimate that in addition to the 68 million vapers there might be a further 30 million people globally using other safer nicotine products, defined as HTP, snus and US smokeless, indicating a global total of 98 million people. Given the paucity of data, this estimate should be read cautiously. The current state of published evidence does not allow for a more sophisticated estimate.

Public health and government survey agencies should make better attempts to monitor use of safer nicotine products, and manufacturers of these products should make more transparent the information they collect. Clearly, global consumer interest in SNP has not been matched by government or academic surveys to explore even the extent of use of these products.

98

million

the estimated number of people globally

using safer nicotine products – vaping products, HTP,

snus, and US smokeless.

Country level data

Our global level estimate is based on extrapolation from national surveys. We have been trying to map the prevalence of vaping on a country basis since 2018 and to date there are only 49 states and territories where we have identified suitably representative data on the prevalence of vaping product use. That is a small change from 2018 when we identified 35 countries with data, and many states and territories have only one data point. In the European Union (EU), the Eurobarometer 2017 survey53 has not yet been repeated. Few countries are undertaking tracking studies to look at changes in use over time – exceptions being the US and the UK. Readers must be aware of limits to the comparability of the sources. Surveys can suffer from numerous differences, due to variations in sampling methods and questions asked. We therefore suggest caution in making country comparisons.54 Prevalence data are even scarcer for HTP – we only managed to find information for one country. Data are available and searchable on a country basis on the GSTHR database.55

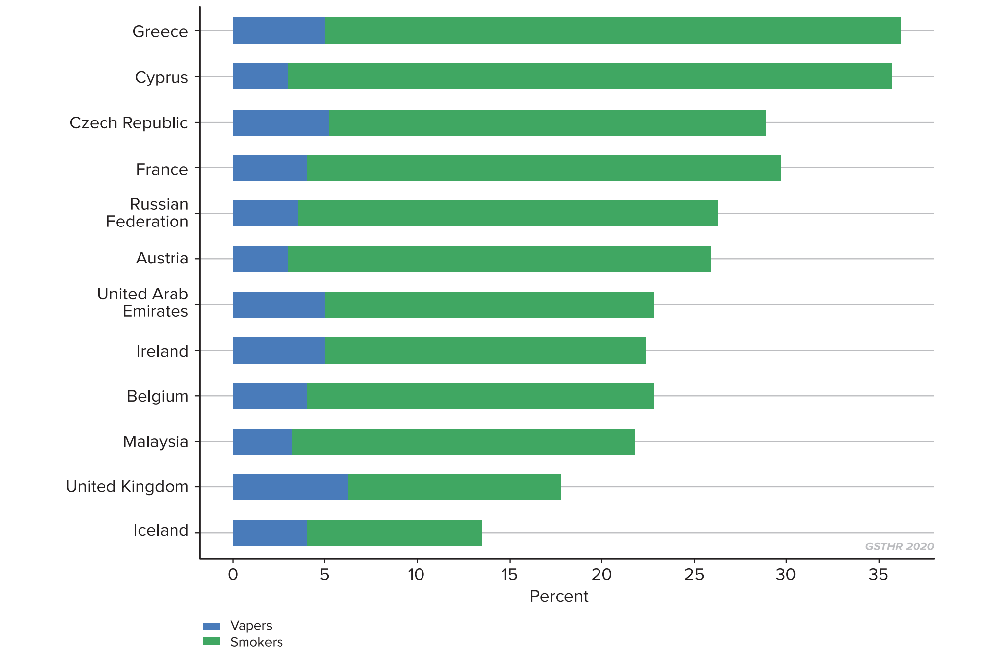

The average prevalence of current vaping product use is 1.6 per cent of the adult population in the EU, as found in the EU Eurobarometer56 survey. A further 13 per cent “used to use them, but no longer do so” or “have tried them once or twice”. 85.6 per cent “have never tried or used them”. Levels of sometime vaping experience range up to 27 per cent of the adult population in Greece, and 20 per cent or above in Estonia, Czech Republic, France, Cyprus, Latvia and Austria. Clearly, there are many smokers who are interested in these products. But there is also a large gap between those who have shown enough interest to have tried vaping at some time, and those who have gone on to currently vape.

Overall, as a percentage of the total adult population, current use of vaping devices in different countries ranges between 1 per cent and 7 per cent.

There are eight countries where the prevalence of vaping is 3 per cent or more including the UK, United Arab Emirates (UAE), US, France, Iceland, Belgium, the Russian Federation and Malaysia.

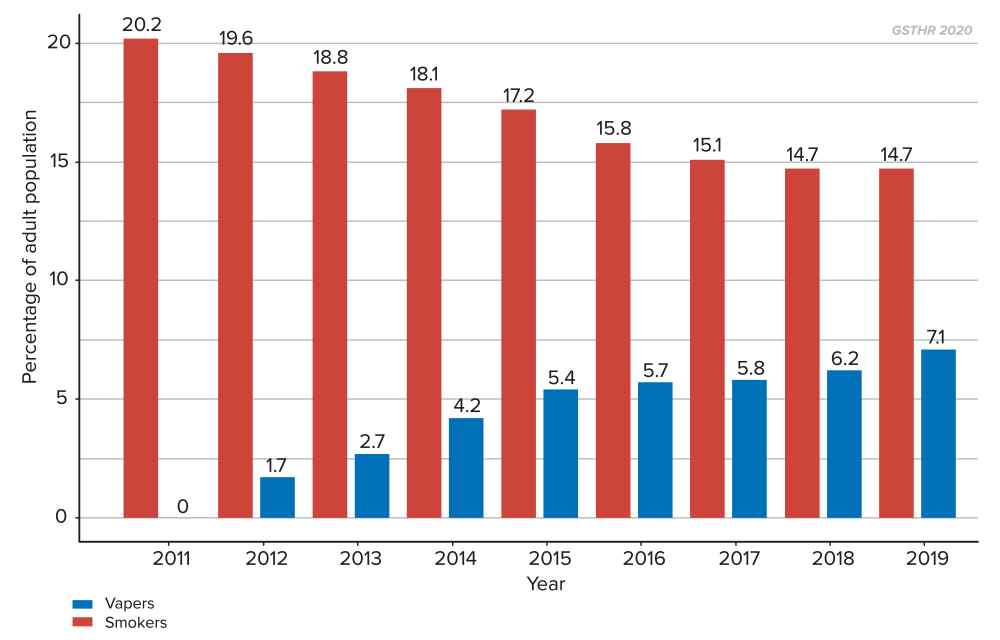

Prevalence of current smoking cigarettes and current vaping

Countries where the prevalence of vaping is 3% or more

Special Eurobarometer 458: Attitudes of Europeans towards tobacco and electronic cigarettes – European Union Open Data Portal. (n.d.). Retrieved 23 June 2020, from https://data.europa.eu/euodp/en/data/dataset/S2146_87_1_458_ENG

Farsalinos, K. E. et al. (2018). Electronic cigarette use in Greece: an analysis of a representative population sample in Attica prefecture. Harm Reduction Journal, 15(1), 20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-018-0229-7

Vaping Linked to Decrease in Cigarette Smoking (Iceland Directorate of Health Newsletter, reported in Iceland Review). (2018, May 3). Iceland Review. https://www.icelandreview.com/news/vaping-linked-decrease-cigarette-smoking/

Healthy Ireland Survey documents. (2019). https://www.gov.ie/en/collection/231c02-healthy-ireland-survey-wave/

McNeill, A. et al. (2020). Vaping in England: 2020 evidence update summary (Research and Analysis). Public Health England (PHE). https://www. gov.uk/government/publications/vaping-in-england-evidence-update-march-2020/vaping-in-england-2020-evidence-update-summary

Windows of opportunity

Japan

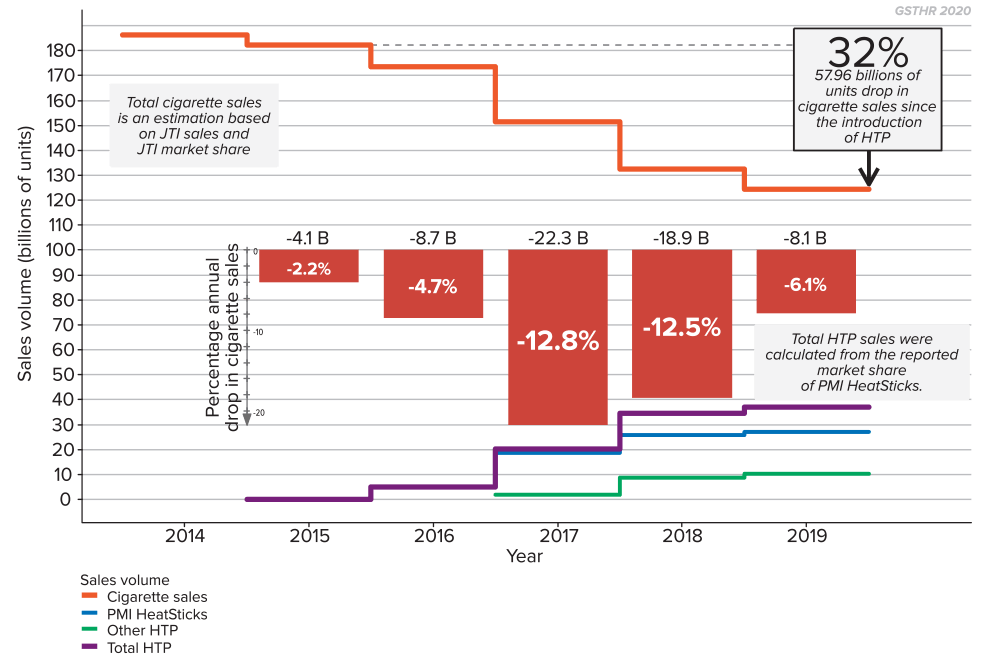

HTP now account for about a third of tobacco sales.57,58 There is a consensus around the following factors to account for this phenomenal rise matched against a dramatic fall in cigarettes sales:

- Interest in innovative technologies

- Relatively high levels of disposable income

- A paradoxical legal situation which on the one hand bans vaping products but on the other, not only allows HTP products to be sold, but gives the companies license to advertise and promote widely alongside a favourable tax regime.

- A cultural ethic whereby Japanese people are very considerate in health terms such that they embrace HTP over cigarettes as being less polluting and irritating to others. Consumer research in Japan revealed that the top two reasons for switching were not having to worry about unpleasant smells nor affecting others and also that they are less harmful than cigarettes.

Cigarette and HTP sales in Japan, 2014–2019

Philip Morris International 2019 Annual Report. (n.d.). Retrieved 16 July 2020, from http://media.corporate-ir.net/media_files/ IROL/92/92211/2020-PMI-FinalFiles/index.html

32

per cent

the drop in the sales of cigarettes in Japan since

the introduction of HTP.

UK

We noted in our previous report the significant rise in vaping and decline in smoking since 2011. Around 7 per cent of the adult population in Great Britain currently vapes59, which equates to around 6 million vapers60. The year on year increase in vaping is matched by the continuing major reduction in smoking in the UK with under 15 per cent of the adult population currently smoking.

Trends in smoking (UK) and e-cigarette use (Great Britain) 2011–2019

Use of e-cigarettes among adults in Great Britain, 2019. (2019). Action on Smoking and Health. https://ash.org.uk/information-andresources/ fact-sheets/statistical/use-of-e-cigarettes-among-adults-in-great-britain-2019/

Iceland

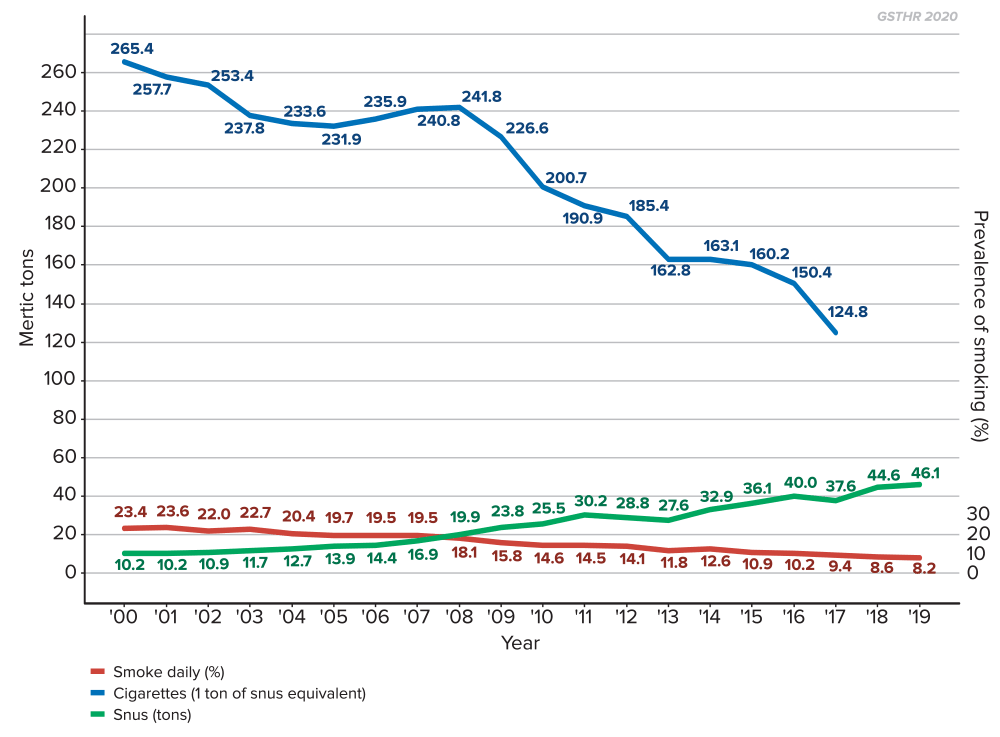

Iceland has witnessed a dramatic decline in smoking to 8.2% in 201961, and has the second lowest adult daily smoking rate in Europe after Sweden.

A long-term decline in smoking accelerated in 2007 and again in 2012.

Market data show, on a weight-for-weight basis, a continued decline in cigarette sales and an increase in snus sales.

Prevalence of adult daily snus use was 3.2% in 201262 rising to 6% in 201963.

Prevalence of adult daily e-cigarette use was 3.6% in 2017.64

It would appear that the uptake of snus and latterly of e-cigarettes has contributed to the long-term decline in smoking.

Most significant is that smoking uptake among young people has virtually disappeared with only 3.3% of 18-24 year old smoking, and 0.8% of 16 year olds65.

Changes in the prevalence of smoking and sales of cigarettes and snus in Iceland

Notes:

Snus sales from Iceland state alcohol stores https://www-statista-com.iclibezp1.cc.ic.ac.uk/statistics/792450/sales-volume-of-snuff-invinbudin- stores-in-iceland/

Cigarette sales based on cartons sold and assuming 0.75g tobacco per cigarette to convert to metric tons.

An unrealised public health success story

What has been lost in all the heat and dust about ‘the dangers of vaping’ is that the use of SNP is one of the most startling public health success stories of modern times. From a standing start around 2006, many people in many countries around the world have taken control of their own health by switching to non-combustible products or reducing their smoking levels through parallel use.

This has been achieved without the intervention of official public health agencies, and often in spite of their best efforts to stop it. Moreover, this public health revolution has been driven by consumers choosing safer nicotine products in preference to combustibles. It has occurred with minimal cost to governments. This is a true bottom up public health success, being driven by a public concerned for their health.

The health revolution in safer nicotine products has been consumer driven and comes at minimal cost to governments.

68 million vaping, 20 million using HTP and 10 million using snus or US smokeless might look like a success, particularly for vaping and HTP which are recent introductions. But is it? A bleak assessment would be not yet. 98 million users of SNP is minuscule compared with continued use of combustible products by 1.1 billion smokers. It only amounts to nine SNP users for every 100 smokers and six vapers for every 100 smokers.

Despite the enthusiasm for safer alternatives, the rate of progress in switching from smoking to SNP is slow. There is an urgent need to scale up tobacco harm reduction. What is needed to make this happen is for products to be:

- Available

Regulation and control should be geared to making these products as readily available as other consumer goods, given that independent and internationally agreed products safety standards are in place. So no outright bans, no flavour bans, no regulation as medicinal products and no exorbitant tobacco-style taxation. Instead, are there ways to incentivise both industry and consumers to switch instead of trying to stub out safer nicotine alternatives? - Affordable

This links to the question of consumers’ ability, especially in lower and middle-income countries, to afford products. A supportive legislative landscape is required, and other obstacles need to be overcome. For example, mobile phones are ubiquitous across Africa with the capacity to charge them up, so affordable, rechargeable vaping devices must be a possibility, if the will is there from the manufacturers. - Appropriate

Vaping devices might work to replace cigarettes in many countries but won’t be appropriate everywhere and with all communities. There are many nicotine consumers, especially in India and South East Asia, who don’t smoke conventional cigarettes but instead smoke local varieties or use a range of even more dangerous smokeless tobacco products. It would be hugely beneficial from a public health perspective if these dangerous smokeless products were replaced by far safer snus-type smokeless products. - Acceptable

However, just because more appropriate safer options could be made available does not mean that the target consumer groups would find them acceptable. Public health and commercial marketing strategies would need to account for long-standing social and cultural custom and practice, the nature of the messaging, who is delivering the messages and by what means.

The rate of progress in switching from smoking to SNP is slow. There is an urgent need to scale up tobacco harm reduction.

It took around 60 years from the invention of the cigarette rolling machine in 1880 to the end of the Second World War to finally dislodge most other forms of tobacco use in high-income countries.

Can we be encouraged by the rate of change from combustible to non-combustible nicotine delivery? The switch to SNP is encouraging, but to date it is not the public health success that it could be. Sixty years is too long to wait. In that time, many millions of people will die prematurely every year from smoking-related diseases.

Later chapters address the obstacles preventing people switching away from combustibles to SNP. Many more people would have switched without the influence of negative campaigning against THR.

Many more people would have switched to SNP without the negative campaigning against THR.

- Bower, J. L., & Christensen, C. M. (1995). Disruptive Technologies: Catching the Wave. https://www.hbs.edu/faculty/Pages/item.aspx?num=6841, p.43-53

- Boroujerdi, R. D. (2014). The search for creative destruction (pp. 1–5). Goldman Sachs Global Investment Research. https://www.goldmansachs.com/investor-relations/financials/ archived/annual-reports/2013-annual-report-files/search.pdf

- Parker-Pope, T. (2001, February 10). ‘Safer’ Cigarettes: A History. https://www.pbs.org /wgbh/nova/article/safer-cigaretteshistory/

- Hasselbalch, J. (2014, November 18). Regulating Disruptive Innovations: The Policy Disruption of Electronic Cigarettes. Global Reordering: Towards the Next Generation of Scholarship conference, Brussels

- Kruger, R. (1996). Ashes to Ashes-America’s Hundred-Year Cigarette War, the Public Health, and the Unabashed Triumph of Philip Morris, NY. Alfred A. Knopf. P.19-20

- The npro-mini also resembled an early NJOY product. http://www.electroniccigarettereview.com/njoy-review-npro-mini/

- Phillips, R. (2007, July 7). Electriciggy: The battery-powered nicotine fix that helps smokers beat the ban. Mail Online. https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-466898/Electriciggy-The-battery-powered-nicotine-fix-helps-smokers-beat-ban.html

- Professor Mayer. Personal communication.

- Mayer, B. Expert opinion on the pharmacology and toxicology of electric cigarette for smoking cessation. Unpublished March 2006.

- https://gsthr.org/resources/item/no-fire-no-smoke-global-state-tobacco-harm-reduction-2018

- A recent article in The Economist revealed that the Chinese vaping manufacturer Smoore is now the world’s most valuable vaping company estimated at $24bn, nearly double the market value of JUUL. But Smoore are likely to face competition from the state-owned China Tobacco Company who are researching the market. Yet another example of the power of disruptive business. A state tobacco monopoly looms over China’s e-cigarette makers. (n.d.). The Economist. Retrieved 23 August 2020, from https://www.economist.com/business/2020/07/23/a-state-tobacco-monopoly-loomsover- chinas-e-cigarette-makers

- Hajek, P. et al. (2020). Nicotine delivery and users’ reactions to Juul compared with cigarettes and other e-cigarette products. Addiction, 115(6), 1141–1148. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.14936

- Foulds, J. et al. (2003). Effect of smokeless tobacco (snus) on smoking and public health in Sweden. Tobacco Control, 12(4), 349–359. https://doi.org/10.1136/tc.12.4.349

- Global Trends in Nicotine. (2018). Foundation for a Smoke-Free World. https://www.smokefreeworld.org/advancingindustry- transformation/global-trends-nicotine/

- E-Cigarettes - worldwide | Statista Market Forecast (adjusted for expected impact of COVID-19). (2020, May). Statista. https://www.statista.com/outlook/50040000/100/e-cigarettes/worldwide

- Personal communication. Tim Phillips, ECigIntelligence.

- Global Tobacco: Key Findings Part II: Vapour Products | Market Research Report | Euromonitor (Strategy Briefing). (2017). Euromonitor International. https://www.euromonitor.com/global-tobacco-key-findings-part-ii-vapour-products/report, p.11

- Investor Information. (2020). Philip Morris International. https://philipmorrisinternational.gcs-web.com/static-files/ d755c6c0-37a2-4eca-b41c-5c43b810520c, slide 67

- Personal communication, data and definitions not provided.

- https://www.gsthr.org/report/full-report-online#ch04

- Brad Rodu. (2014, August 8). How many Americans use smokeless tobacco? R Street. https://www.rstreet.org/2014/08/08/ how-many-americans-use-smokeless-tobacco/

- CDCTobaccoFree. (2018, August 29). Smokeless Tobacco Use in the United States. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/smokeless/use_us/index.htm

- How many snus users are there in Sweden? (n.d.). Swedish Match. Retrieved 23 August 2020, from https://www. swedishmatch.ch/en/what-is-snus/qa/how-many-snus-users-are-there-in-sweden/

- Personal communication, data and definitions not provided.

- Special Eurobarometer 458: Attitudes of Europeans towards tobacco and electronic cigarettes – European Union Open Data Portal. (n.d.). Retrieved 23 June 2020, from https://data.europa.eu/euodp/en/data/dataset/S2146_87_1_458_ENG

- Farsalinos, K. E. et al. (2016). Electronic cigarette use in the European Union: analysis of a representative sample of 27 460 Europeans from 28 countries. Addiction, 111(11), 2032–2040. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.13506

- See www.gsthr.org/countries. Larger companies will have detailed sales and consumer data, but these are regarded as commercially sensitive.

- Special Eurobarometer 458: Attitudes of Europeans towards tobacco and electronic cigarettes – European Union Open Data Portal. (n.d.). Retrieved 23 June 2020, from https://data.europa.eu/euodp/en/data/dataset/S2146_87_1_458_ENG

-

A special issue of the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health dealt exclusively with aspects

of HTP use in Japan including the mapping of cigarette against HTP sales; use of HTP with other products; indoor use of

HTP; perceptions of relative risk and use by young people.

IJERPH | Special Issue: Japan: Evaluating the Effectiveness of Tobacco Control Policies and the Use of Heated Tobacco Products. (n.d.). Retrieved 23 August 2020, from https://www.mdpi.com/journal/ijerph/special_issues/Japan_evaluating_ effectiveness_tobacco_control_policies_use_heated_tobacco_products# - Cummings, K. M. et al. (2020). What Is Accounting for the Rapid Decline in Cigarette Sales in Japan? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(10), 3570. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17103570

- For an up to date assessment of SNP use in England see; West, R et al. Trends in electronic cigarette use in England. Smoking toolkit study 2020. www.smokinginengland.info/latest-statistics

- Great Britain is England, Scotland and Wales. The United Kingdom (UK) is England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland – vaping prevalence in the UK is approximately five percent.

- Statistics Iceland | Smoking habits by sex and age 1989-2018. (n.d.). Statistics Iceland. Retrieved 3 September 2020, from https://px.hagstofa.is/pxen/pxweb/en/Samfelag/Samfelag__heilbrigdismal__lifsvenjur_heilsa__1_afengiogreyk/HEI07102. px/?rxid=e93275f5-10ff-46e9-aea7-bd1bc6bee345

- Allt talnaefni – Statistics. (n.d.). Retrieved 3 September 2020, from https://www.landlaeknir.is/tolfraedi-og-rannsoknir/ tolfraedi/allt-talnaefni/, https://www.landlaeknir.is/servlet/file/store93/item35873/31_toba9_Tobak_i_vor_UTGEFID.pdf

- Directorate of Health data – personal communication, Karl Snæbjörnsson

- Allt talnaefni – Statistics. (n.d.). Retrieved 3 September 2020, from https://www.landlaeknir.is/tolfraedi-og-rannsoknir/ tolfraedi/allt-talnaefni/, https://www.landlaeknir.is/servlet/file/store93/item35874/33_toba11_Rafsigarettur_UTGEFID.pdf

- Directorate of Health data – personal communication, Karl Snæbjörnsson