Smoking: the slow-burning killer

Wherever you sit in the debate about THR there is no denying the statistics on global smoking are grim.

Progress in helping people shift away from smoking is slow. Globally, levels of smoking have hardly changed since our 2018 report. There continue, however, to be some positive changes in a few countries, linked to the uptake of SNP which we discuss in the next chapter.

Smoking is one of the world’s biggest health problems:

- Half of all those who smoke will die prematurely from smoking-related diseases.

- The Global Burden of Disease study estimates that smoking accounted for 7.1 million premature deaths in 2017, with an additional 1.2 million deaths attributed to secondhand smoke.3 This makes it the second highest risk factor for death behind high blood pressure.

- Thirteen per cent of global deaths were attributed directly to smoking in 2017, and a further two per cent due to second-hand smoke.4

- Three times more people die prematurely from smoking than from the total combined deaths from malaria (405,000 in 2018)5, HIV (770,000) 6 and TB (1.5 million)7.

3

three times more people die from a smoking related disease than

from malaria, HIV and TB combined.

1

billion

the estimated number of smoking-related deaths by 2100 – equivalent to the deaths of the

whole populations of Indonesia, Brazil, Bangladesh, Nigeria and the Philippines.

The WHO estimates that, based on current forecasts, one billion people will have succumbed to a smoking-related disease by the end of this century.8 That’s equivalent to the whole populations of Indonesia, Brazil, Nigeria, Bangladesh and the Philippines dying from COVID-19.

Burning tobacco is the most common way to ingest nicotine. Cigarettes make up about 89 per cent of tobacco products by sales value, and all combustible products combined comprise 96 per cent of the nicotine market by retail sales value (see also Chapter 2). These other forms of combustible tobacco products include cigars, kreteks (clove cigarettes favoured in Indonesia), bidis (hand-rolled cigarettes popular in South East Asia) and shisha (smoking tobacco filtered through water in waterpipes, found in many Middle Eastern countries).

Nicotine is one of the world’s most widely consumed drugs alongside caffeine and alcohol.

The WHO indicates a further 346 million adults use smokeless tobacco products worldwide. The majority (about 86 per cent) of smokeless tobacco consumers live in southeast Asia. There is however a wide range of smokeless products with different risk profiles. ‘Smokeless tobacco’ is a misleading and confusing term when applied to Asian tobaccos which contain several hazardous products, in addition to tobacco. In this report, unless otherwise indicated, we define those safer smokeless tobacco products as US smokeless and Swedish snus type manufactured products.

Nicotine is one of the world’s most widely consumed drugs alongside caffeine and alcohol.9 Smoking is ubiquitous, but 80 per cent of deaths related to smoking occur in LMIC,10 which in turn comprise about 85 per cent of the global population.

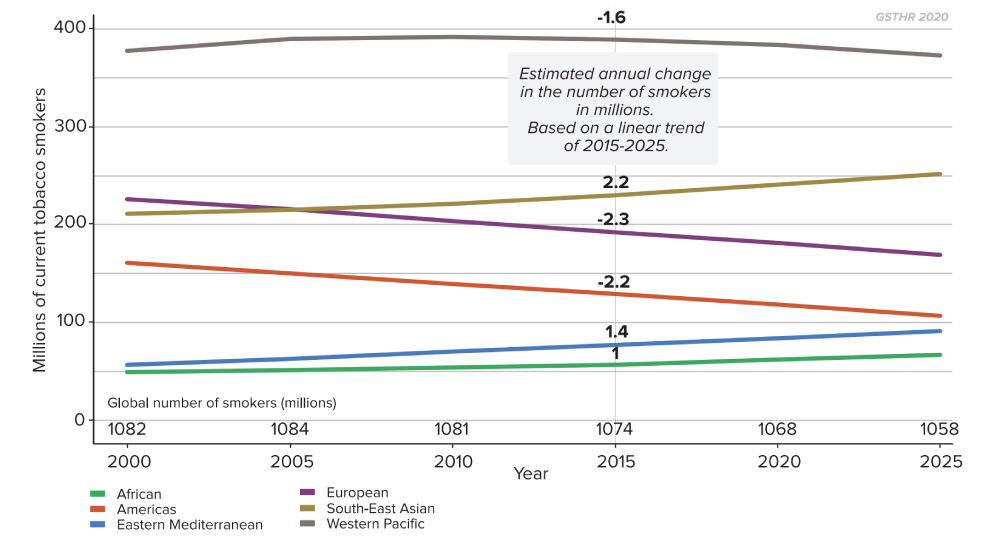

Smoking is not disappearing. There are as many smokers in 2020 as there were in 2000, when it was estimated that there were 1.1 billion smokers. The WHO projects that it will remain at around 1.1 billion until at least 2025.11 Population growth has offset the decline in the proportion of smokers in the population.

1.1

billion

the estimated number of smokers globally, unchanged since the year 2000.

Number of adult tobacco smokers by WHO region, 2000–2025 (projected)

Some regions now have more smokers than in 2000 and are projected to have even more by 2025, including the African, Eastern Mediterranean, and South East Asian regions. The absolute number of smokers is declining in the European region, the Western Pacific and the Americas.

Which countries currently have the highest levels of daily adult smoking?

Around one in five adults (19 per cent) in the world smokes tobacco.12

Many countries have much higher levels of smoking. There are 22 countries where 30 per cent or more of the overall adult population are current smokers. This includes Pacific islands such as Kiribati and the Solomon Islands, several European countries including Serbia, Greece, Bulgaria, Latvia and Cyprus, Lebanon in the Middle East, and Chile in South America.

Go to https://gsthr.org/countries for country-level information on smoking.

It is worth recalling that such high levels of smoking were not uncommon in many countries in the past: for example, in the UK in the mid-1970s, 46 per cent of adults smoked.

Around the world high levels persist, despite major global initiatives led by WHO to reduce smoking – and despite the investment of millions of dollars in tobacco control to reduce the demand for and supply of tobacco (See Chapter 5).

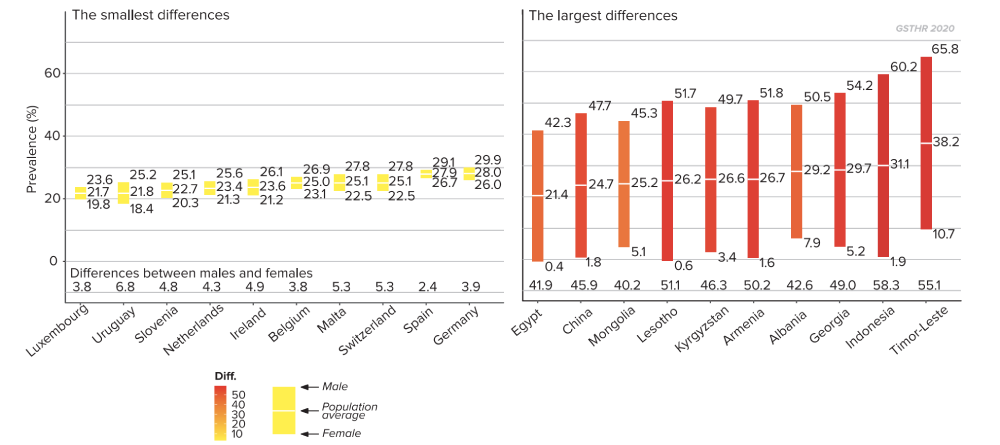

Average levels of smoking at a national level hide significant differences in the levels of smoking between males and females. Almost one third of men (30 per cent) globally smoke compared with 10 per cent of women.13

Countries with the smallest and largest difference between levels of adult tobacco smoking for males and females

Current tobacco smoking, age standardized 2018 point estimations.

According to WHO data for 2018, the prevalence of current tobacco smoking among men in 35 countries is above 40 per cent. This ranges from a staggering 69 per cent in Kiribati, to 50 per cent in in Albania, Cyprus, Kyrgyzstan and Latvia, 45 per cent in Greece, Mongolia and Republic of Moldova and 41 per cent in Ukraine, the Russian Federation, Bangladesh and Samoa.14

In a few high-prevalence countries, the level of female smoking is higher than the male smoking levels found in lower prevalence countries for example, in Kiribati, Nauru, Chile and Serbia, over 40 per cent of women smoke compared to 78 other countries where less than 30 per cent of men smoke.

In some indigenous communities, such as the Māori, more women smoke than men (see Chapter 7). There is some evidence that for cultural or social reasons in some countries, there may be under-reporting of female smoking.17,18

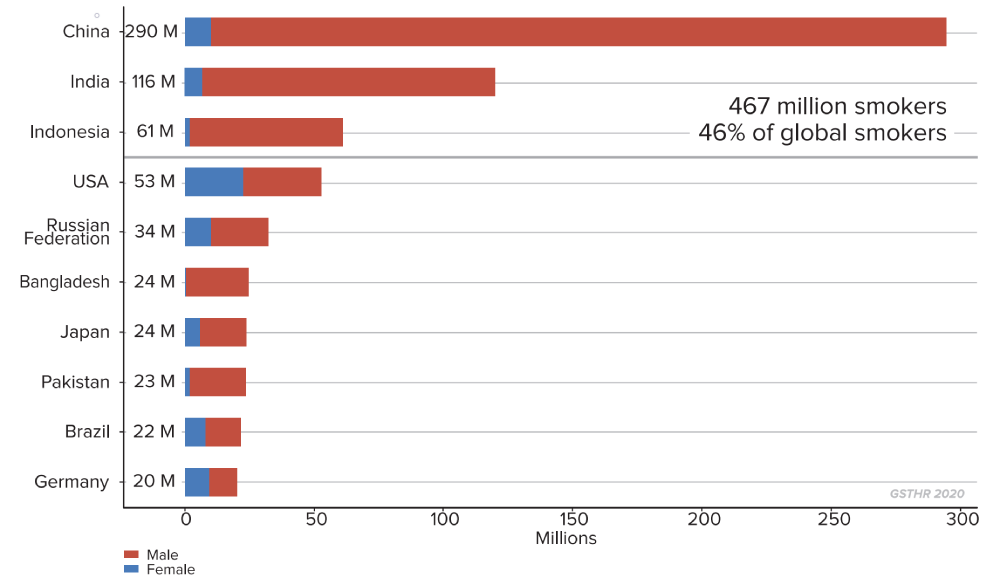

Which countries have the most smokers?

Nearly half the world’s smokers (46 per cent) live in just three countries.

China has the largest number of current smokers at 290 million, followed by India at 116 million and Indonesia at 61 million. Together, these countries account for 467 million smokers.

Countries with the highest number of current tobacco smokers

Population 2018, 15+

467

million

smokers – nearly half the global total – live in just three countries: China, India and Indonesia.

What are the trends in smoking?

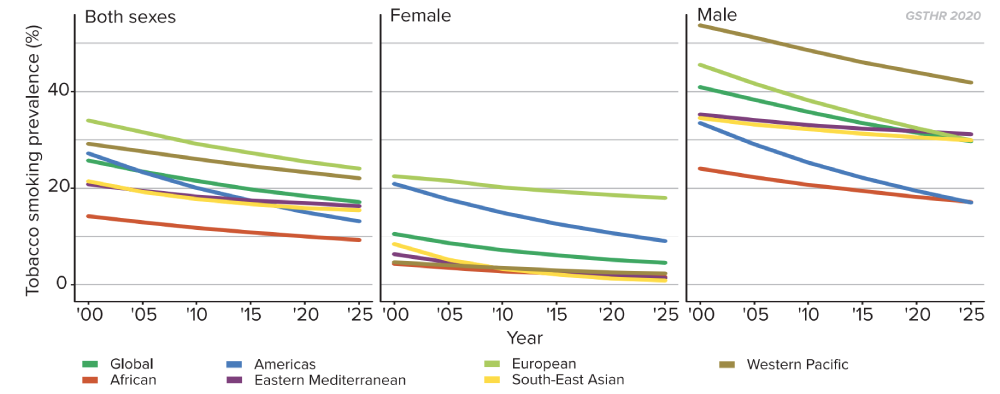

Historically, most countries have seen a rise and then a decline in smoking. Sales of cigarettes took off around the year 1900 in richer countries, peaked by the 1980s and have since declined.19 A general decline in rates of smoking is apparent across all global regions, and for both sexes.

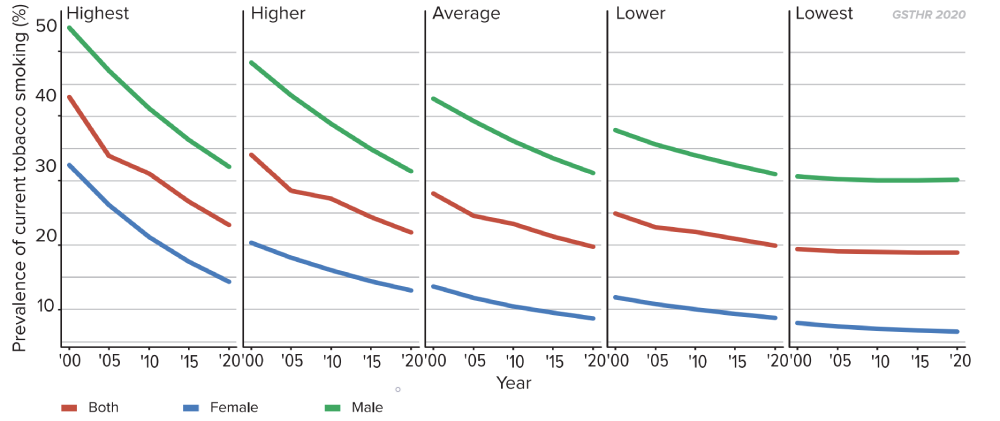

Tobacco smoking prevalence, 2000–2025 (projected)

Females and males, age-standardized average for WHO regions

This has been especially marked in many higher-income countries. Rates of smoking have fallen for both men and women largely due to greater public awareness of the importance of a healthier lifestyle, as well as the introduction of various tobacco control measures including advertising bans, smoke-free environments, and higher taxation. Nevertheless, reduction in smoking prevalence tends to start plateauing at around 20% of a population, suggesting diminishing returns on tobacco control interventions. In the chart, we group countries in terms of the drop in the prevalence of current tobacco smoking, from those countries with the highest drop in prevalence to those with the lowest drop. Across all groups there tends to be a levelling at around 20 per cent.

2000–2020 prevalence of tobacco smoking

Countries grouped from the highest to lowest drops in percent prevalence

What these data show is that millions of people are still smoking, many of whom will want to, but have been unable, to quit. We discuss this in later chapters, where we consider the limits of tobacco control interventions and the need to adopt harm reduction measures for people who don’t want to smoke but want to continue using nicotine.

However, it is not all bad news. There are some notable exceptions – countries which fall well below the 20 per cent marker. This is particularly noticeable in countries where SNP are replacing combustible tobacco such as the UK, Sweden and Norway.

Reductions in smoking levels are to be welcomed, but progress is slow. The WHO set aspirations for the global reduction of tobacco use (both smoking and smokeless tobacco) by 30% between 2010 and 2025.20 Globally, the WHO estimates that only 32 out of 149 countries (for which measures are available) are likely to achieve this.

4

in

5

the number of countries that will not meet WHO target reductions in smoking by 2025.

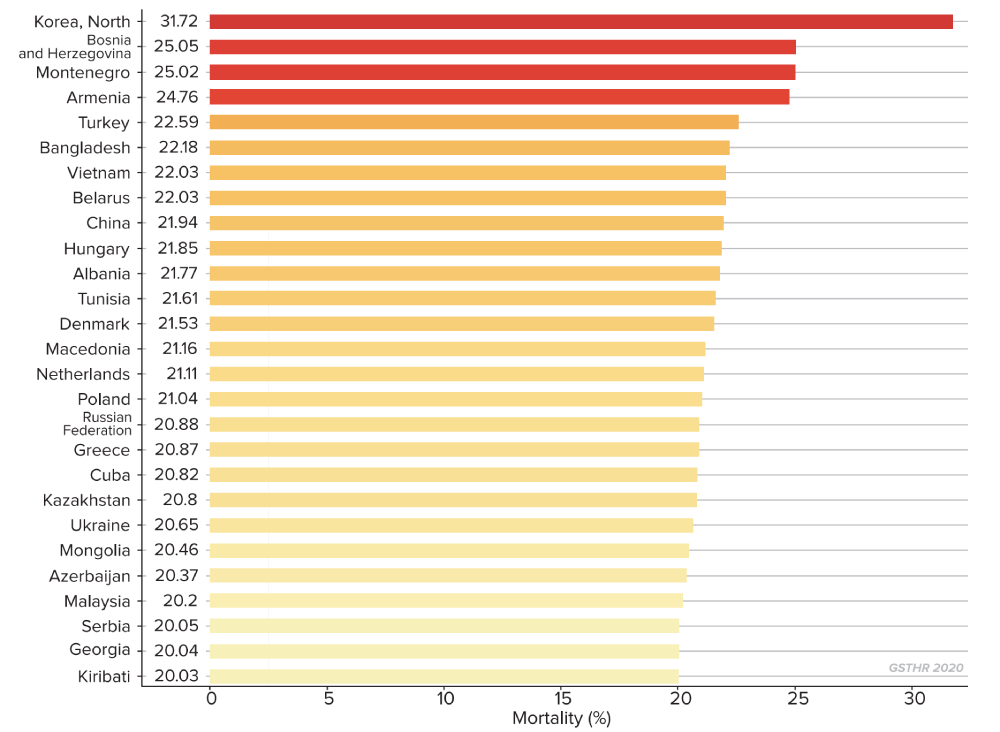

Levels of smoking-related mortality remain high

Slow progress means that deaths from smoking remain high. This is linked both to the current prevalence of smoking, and the legacy of smoking in previous years. There are 27 countries where 20 per cent or more of deaths are attributable to smoking.

Countries with the highest levels of mortality attributable to smoking tobacco

(over 20% of all deaths)

In addition to the huge human toll of illness and death there is the enormous cost to the global economy. Considering both direct costs of hospital care and medication, and indirect costs of lost productivity, it has been calculated that the annual global cost of smoking-related disease and death amounts to $1.4 trillion.21 Extrapolated to the end of the century, the figure comes to $112 trillion. According to the 2019 World Bank data, this is $24 trillion more than current annual global GDP.22

$

1.4

trillion

the estimated annual global cost of smoking.

Global smoking trends and global tobacco policy

The trends in smoking are in the right direction, but by any metric progress is slow: the question is, what could speed it up?

The WHO makes much of the extent to which tobacco control measures have been introduced in many countries. While it laments slow progress on reducing the prevalence of smoking, the overarching message from the WHO is that its global tobacco control strategy is working, as more countries adopt tobacco control measures, for example, at a legislative level.

Yet passing legislation through a parliament is one thing. Enforcing the law is a different matter in countries which lack the necessary administrative, financial and enforcement resources, not to mention the political will, to do so. This lack of will is not confined to those countries with a vibrant tobacco agriculture; even on health grounds, officials in Africa, for example would prioritise dealing with infectious diseases over tobacco control.

The degree to which countries can implement and enforce policies rather than simply signing up to good intentions is notably split between high income countries and LMIC. As the authors of The global tobacco control ‘Endgame’ point out, effective national implementation of the provisions of the 2005 FCTC to which most countries signed up is very much dependent on the overall public health climate.

“We identify the most relevant characteristics of the policy processes within ‘leading’ countries with the most comprehensive tobacco control: their department of health has taken the policy lead (replacing trade and treasury departments); tobacco is ‘framed’ as a pressing public health problem (not an economic good); public health groups are more consulted (often at the expense of tobacco companies); socioeconomic conditions (including the value of tobacco taxation, and public attitudes to tobacco control) are conducive to policy change; and, the scientific evidence on the harmful effects of smoking and second-hand smoking are ‘set in stone’ within governments. These factors tend to be absent in the countries with limited controls. We argue that, in the absence of these wider changes in their policy environments, the countries most reliant on the FCTC are currently the least able to implement it.” 23,24

The WHO asserts that the slow progress towards reducing smoking levels in poorer countries is because the introduction of strong tobacco control policies in these countries has been impeded by lobbying from the tobacco industry. It also cites, somewhat more obscurely, “setbacks, unexpected barriers…and difficult political barriers to overcome.”25

There is a wider global concern here which relates to the UN 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. The preamble states that, “This Agenda is a plan of action for people, planet and prosperity. It also seeks to strengthen universal peace in larger freedom. We recognize that eradicating poverty in all its forms and dimensions, including extreme poverty, is the greatest global challenge and an indispensable requirement for sustainable development”, and that “nobody will be left behind”. 26

Goal 3 of the agenda is to “ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages” with a target (3.4) of reducing premature deaths from non-communicable diseases (NCD) by one third by 2030. But as the recent WHO NCD report notes, “Country actions against NCDs are uneven at best. National investments remain woefully small and not enough funds are being mobilized internationally… There is no excuse for inaction, as we have evidence-based solutions.” (WHO, 2018)

The top three causes of NCD mortality are cardiovascular disease, cancer and respiratory disease; all closely associated with cigarette smoking. When the American Cancer Society published the first edition of the Tobacco Atlas in 2002, the authors wrote, “The publication of this Atlas marks a critical time in the epidemic. We stand at the crossroads with the future in our hands.” In the fifth edition (2015) they added, “These words are as true today as they were then.”

The Atlas authors wrote about standing at the crossroads. Now, the promise of THR has carved out a new path to take. Back in 2002, smokers had just two roads to choose from: which has been caricatured as a choice between ‘Quit’ or ‘Die’. The main thrust of tobacco control strategy has been to make smoking less attractive to and more difficult for smokers, focusing on supply (industry-related) and demand (consumer-related) interventions.

In 2007, the WHO launched its MPOWER tobacco control strategy as an implementation guide to the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) which has the following components:

- Monitor tobacco use and prevention policies.

- Protect people from tobacco smoke.

- Offer help to quit tobacco use.

- Warn about the dangers of tobacco.

- Enforce bans on tobacco advertising, promotion and sponsorship.

- Raise taxes on tobacco.

The main thrust of tobacco control is to make smoking less attractive and more difficult for smokers, focusing on supply (industry-related) and demand (consumerrelated) interventions.

In terms of the health of current smokers, the most important strand is offering help to quit smoking – for example, through the provision of smoking cessation services which smokers can access for little or no charge.

In the 2019 report on the global tobacco epidemic, the WHO admitted: “cessation policies are still among the least implemented of all WHO FCTC demand reduction measures, with only 23 countries in total [out of 195] providing best-practice cessation services, the majority of which are high-income countries.” It goes on to say: “if tobacco cessation measures had been adopted at the highest level of achievement in 14 countries between 2007 and 2014, 1.5 million lives could have been saved”. 27

On the vital question of saving lives then, MPOWER is clearly insufficient. Its implementation by international donors and national and local agencies (see Chapter 5) focuses too much on process and output indicators (the number of countries adopting various measures) rather than outcomes – a decline in smoking. 28 The one in five of the adult population still smoking deserve additional options.

MPOWER alone is insufficient: the one in five of the adult population still smoking deserve additional options.

Smokers who cannot or do not wish to either quit or die have a third route to reduce the risk of death or disease. THR, through the use of SNP, has the potential to substantially reduce the global toll of death and disease from smoking, and to effect a global public health revolution – and all at marginal or no cost to governments. This is now more vital than ever, as the public purse of every nation will be stretched to breaking point attempting to recover from the economic aftershocks of the coronavirus pandemic.

In the development of this alternative to ‘quit or die’, public health as a body of professional organisations has had little impact. In fact, it is consumers who have led the charge to develop and embrace alternative forms of nicotine, in products that both work and are desirable. Consumers have shown us that it is possible for the world to move away from smoking forever.

- Reitsma, M. B. et al. (2017). Smoking prevalence and attributable disease burden in 195 countries and territories, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. The Lancet, 389(10082), 1885–1906. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30819-X

- Ritchie, H., & Roser, M. (2013). Smoking. Our World in Data. https://ourworldindata.org/smoking

- Fact sheet about Malaria. (n.d.). Retrieved 23 August 2020, from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ malaria

- WHO | Number of deaths due to HIV. (n.d.). WHO; World Health Organization. Retrieved 23 August 2020, from http://www.who.int/gho/hiv/epidemic_status/deaths/en/

- Tuberculosis (TB). (n.d.). Retrieved 23 August 2020, from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ tuberculosis

- Hitti, M. (n.d.). 1 Billion Tobacco Deaths This Century? WebMD. Retrieved 23 August 2020, from https://www.webmd.com/ smoking-cessation/news/20080207/1-billion-tobacco-deaths-this-century

- Crocq, M.-A. (2003). Alcohol, nicotine, caffeine, and mental disorders. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 5, 175–185.

- Anderson, C. L. et al. (2016). Tobacco control progress in low and middle income countries in comparison to high income countries. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 13(10). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph13101039

- WHO Global Report on Trends in Prevalence of Tobacco Use 2000–2025, third edition. (2019). World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/who-global-report-on-trends-in-prevalence-of-tobacco-use-2000-2025-third- -edition

- Ritchie, H., & Roser, M. (2013). Smoking. Our World in Data. https://ourworldindata.org/smoking#share-who-smoke

- WHO global report on trends in prevalence of tobacco use 2000–2025, third edition. (2019). World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/who-global-report-on-trends-in-prevalence-of-tobacco-use-2000-2025-third-edition

- Countries where 40 per cent or more adult males smoke: 69 per cent in Kiribati; 66 per cent in Timor-Leste; 60 per cent in Indonesia; 56 per cent in Solomon Islands; 54 per cent in Georgia; 52 per cent in Tuvalu, Armenia and Lesotho; 50 per cent in Albania, Cyprus, Kyrgyzstan and Latvia; 49 per cent in Chile; 48 per cent in Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Tonga and China; 46 per cent in Bosnia and Herzegovina and Nauru; 45 per cent in Greece, Mongolia and Republic of Moldova; 43 per cent in Belarus, Tunisia and Malaysia; 42 per cent in Bulgaria, Egypt, Fiji, Kazakhstan, Philippines and Turkey; 41 per cent in Ukraine, Russian Federation, Bangladesh and Samoa.

- WHO global report on trends in prevalence of tobacco use 2000–2025, third edition. (2019). World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/who-global-report-on-trends-in-prevalence-of-tobacco-use-2000-2025-third-edition.

- Department of Economic and Social Affairs (Ed.). (2019). World Population Prospects 2019 (Online Edition Rev. 1.; Population Division). United Nations. https://population.un.org/wpp/Download/Standard/Population/

- Roth, M. A. et al. (2009). Under-reporting of tobacco use among Bangladeshi women in England. Journal of Public Health, 31(3), 326–334. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdp060.

- Li, H. C. W. et al. (2015). Smoking among Hong Kong Chinese women: Behavior, attitudes and experience. BMC Public Health, 15(1), 183. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-1529-4. Increasing smoking rates among women could be a hidden dimension to the smoking epidemic. For example, smoking among Hong Kong women rose over 70 per cent from 1990–2012.

- Hoffman, S. J. et al. (2019). Impact of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control on global cigarette consumption: quasi-experimental evaluations using interrupted time series analysis and in-sample forecast event modelling. BMJ, 365. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l2287

- WHO | Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of NCDs 2013-2020. (n.d.). WHO; World Health Organization. Retrieved 23 August 2020, from http://www.who.int/nmh/events/ncd_action_plan/en/

- Goodchild, M. et al. (2018). Global economic cost of smoking-attributable diseases. Tobacco Control, 27(1), 58–64. https://doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-053305

- List of countries by GDP (nominal). (2020). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=List_of_countries_by_ GDP_(nominal)&oldid=974300848

- Cairney, P., & Mamudu, H. (2014). The global tobacco control ‚Endgame’: Change the policy environment to implement the FCTC. Journal of Public Health Policy, 35(4), 506-517.

- There are also some serious questions to be raised about the funding of tobacco control programmes in Africa – see Chapter 5.

- WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic 2019. (2019). World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/tobacco/ global_report/en/, p. 60

- Transforming our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (A/RES/70/1). (2015). United Nations. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/post2015/transformingourworld/publication, p. 5

- WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic 2019. (2019). World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/tobacco/ global_report/en/, p. 10

- One study estimated that those countries which had implemented MPOWER to the ‘highest levels of achievement’ have seen the more rapid falls in smoking levels. But most of those countries cited were in northern Europe and Australia, which had seen significant declines in smoking well before the strategy was in place. Gravely, S. et al. (2017). Implementation of key demand-reduction measures of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control and change in smoking prevalence in 126 countries: an association study. The Lancet Public Health, 2(4), e166–e174. https://doi. org/10.1016/S2468-2667(17)30045-2