The paper is available for download (PDF) in following languages:

English Arabic Chinese (Mandarin) French German Hindi Indonesian Japanese Polish Portuguese Russian Spanish SwahiliFrom 5 - 10 February 2024, government delegations from around the world will meet in Panama City to discuss tobacco and nicotine policy at the rescheduled Tenth Meeting of the Conference of the Parties (COP) to the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC). Decisions taken at these meetings influence how international tobacco control policies are implemented at a national level. These decisions will be very significant in determining the future of safer nicotine products (SNP), such as nicotine vapes (e-cigarettes), snus, nicotine pouches and heated tobacco products. Consumer access to these products is crucial to realise the public health potential of tobacco harm reduction in the global fight against tobacco-related death and disease.

This GSTHR Briefing explains what the FCTC is, what COP meetings are and how they operate. It ends with some preliminary notes on the upcoming COP 10 regarding discussions potentially relevant to SNP. However, you can now also read our Briefing Paper that analyses the published Agenda and supporting documents and considers the potential implications for the future of safer nicotine products and tobacco harm reduction.

What is a Framework Convention?

A treaty is normally understood to be a binding formal agreement that establishes obligations between two or more states on matters that pertain to the interests of those states. However, with some global issues it is difficult to get agreement on the wording of an overarching treaty that binds all the countries involved. Instead, a framework convention establishes broader commitments and leaves the setting of specific actions and targets, either to subsequent more detailed agreements (usually called protocols), or to national legislation. The framework model is used in the Framework Convention on Climate Change and the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control.

What is the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC)?

The FCTC is an international agreement developed in response to the international nature of the public health challenge of tobacco use and smoking.[i] It was the first treaty negotiated under the auspices of the World Health Organization (WHO). After four years of negotiations, the WHO FCTC was adopted by the World Health Assembly on 21 May 2003 and entered into force on 27 February 2005. The text of the Convention can be found here.[ii] The treaty is elaborated in a number of guidelines.[iii]

To date, 182 countries have both signed and ratified the FCTC,[iv] meaning it has been approved at the national level. These countries are referred to as Parties to the Convention. Six countries have signed the Convention but not ratified it. Nine have done neither. Paradoxically, several Parties to the Convention have monopoly or substantial stakes in their own domestic or state-owned tobacco companies.

The Preamble to the FCTC has several recitals (giving context to the Convention) which recognise the need to reduce death and disease from the use of tobacco. These recitals are given within the context of the universal right to health.

» Reflecting…the devastating worldwide…consequences of…exposure to tobacco smoke.

» Seriously concerned about increase in worldwide consumption…particularly in developing countries…

» Recalling Article 12 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights… which states that it is the right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health.

» Determined to promote measures of tobacco control based on current and relevant scientific, technical and economic consideration.

What does the FCTC cover?

The provisions of the FCTC are set out in a number of articles.

The scope of the convention is laid out in Article 1.d which defines tobacco control as “a range of supply, demand and harm reduction strategies that aim to improve the health of a population by eliminating or reducing their consumption of tobacco products and exposure to tobacco smoke”.

Article 5.3 requires that “in setting and implementing their public health policies with respect to tobacco control, Parties shall act to protect these policies from commercial and other vested interests of the tobacco industry in accordance with national law”.

Subsequent articles deal with measures deemed to be necessary to reduce both demand for and supply of tobacco products. There are no articles dealing specifically with harm reduction.

Measures relating to the reduction of demand for tobacco:

Article 6: Price and tax measures to reduce the demand for tobacco

Article 7: Non-price measures to reduce the demand for tobacco

Article 8: Protection from exposure to tobacco smoke 3

Article 9: Regulation of the contents of tobacco products

Article 10: Regulation of tobacco product disclosures

Article 11: Packaging and labelling of tobacco products

Article 12: Education, communication, training and public awareness

Article 13: Tobacco advertising, promotion and sponsorship

Article 14: Demand reduction measures concerning tobacco dependence and

cessation

Measures relating to the reduction of the supply of tobacco:

Article 15: Illicit trade in tobacco products

Article 16: Sales to and by minors

Article 17: Provision of support for economically viable alternative activities

Article 18: Protection of the environment and the health of persons

What is the Conference of the Parties (COP)?

The Conference of the Parties (COP) is the governing body of the Convention. It meets every two years and is where in-person discussions, negotiations and decisions about the implementation of the FCTC and international tobacco control measures take place between the Parties.

Who attends the COP meeting?

The Parties are the decision makers. Parties (countries that have both signed and ratified the FCTC, or who have acceded to the FCTC), can take an active role in discussions and decisions. Signatories (countries that have signed but not ratified the convention) have observer status and can intervene during the discussions; these include the USA, Argentina, Morocco, Cuba, Switzerland and the Dominican Republic.

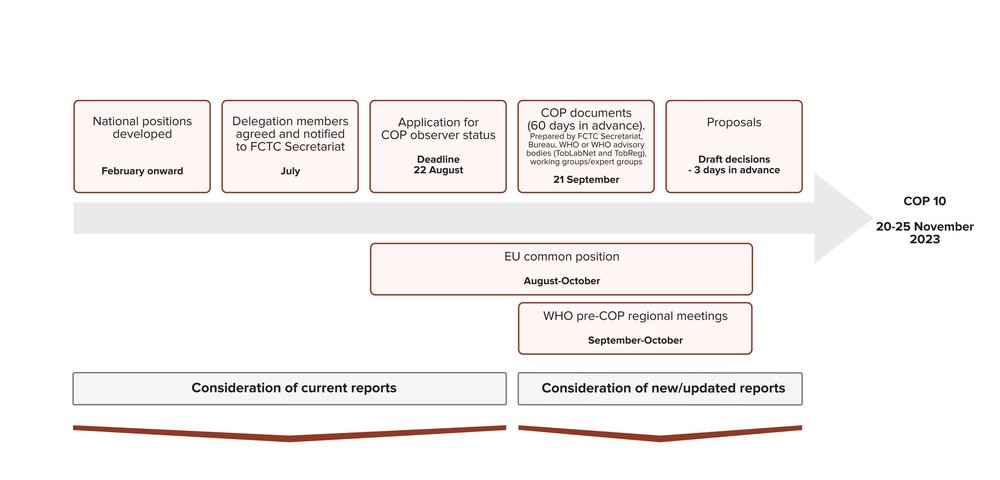

The positions that Parties take are usually discussed well before the COP, with like-minded countries and the WHO trying to align and build coalitions. Much of the discussion and positioning goes on in the “Pre-COP” meetings organized by the WHO and the FCTC Secretariat with each of the six WHO Regions (Africa, Americas, Europe, Western Pacific, South-East Asia and Eastern Mediterranean). Parties can speak for themselves at the COP but are encouraged to allow the region’s nominated country to lead. The EU has its own procedures and the Working Party on Public Health meets to discuss the COP agenda and form policy positions ahead of the COP, known as the “EU Common Position” (the mandate for the EU Commission to present the unified view of its 27 Member States).

Delegations primarily consist of health officials, although other domestic departmental interests concerning, for example, finance, business and trade, might also attend. Non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and subject specialists may also be represented on delegations.

At COP meetings, decisions are taken by consensus and although there is a voting procedure, it has never been used. In theory, every Party carries equal weight, although the most vocal Parties are the ones driving decisions.

Bodies who contribute to the COP meetings

Although Parties are the ultimate decision makers, a number of other bodies have considerable influence on the agenda, the provision of documents and the tone and substance of the meeting.

The FCTC Secretariat

The role of the FCTC Secretariat[v] is to support and implement the business of the COP between meetings.

While in theory this body simply administers the COP, it plays a significant role in determining what the final agenda looks like, as well as shaping the policy direction. The Secretariat organises many of the meetings which take place between each COP, providing agendas and documents, and it has a wider advocacy role in promoting the FCTC aims and objectives across the UN. It also supports the work of the FCTC Knowledge Hubs.[vi]

The Secretariat is funded by the Parties, both in the form of assessed contributions for mainstream Secretariat work, and voluntary contributions for specific projects. The assessment is made based on a formula related to gross domestic product (GDP).

The WHO

The WHO hosts the FCTC Secretariat.

The WHO provides much of the documentation that informs the COP, for example, the Report on Research and Evidence on Novel and Emerging Tobacco Products[vii] and the reports from the WHO Study Group on Tobacco Product Regulation (TobRegNet).[viii] Another report comes from The Tobacco Laboratory Network (TobLabNet)[ix] which develops standard testing and measurement methods for tobacco products.

The Bureau of the Conference of the Parties

The six members of the Bureau of the Conference of the Parties[x] are elected at the end of each COP. The Bureau meets regularly to prepare everything for the following COP session. It also:

» supervises intersessional work including working groups/expert groups;

» consults with the FCTC Secretariat to define the agenda for COP sessions;

» provides guidance to the Secretariat in the preparation of reports, recommendations and draft decisions submitted to the COP;

» reviews applications of NGOs and intergovernmental organisations for observer status;

» works with Regional Coordinators and FCTC Secretariat before and during the COP.

The current members of the Bureau are: Africa Region – Ms Zandile Dhlamini (Eswatini), Americas Region – Dr Marcos Dotta (Uruguay), European Region – Mr Roland Driece (Netherlands), Western Pacific Region – Ms Karlie Brown (Australia), South-East Asia Region – Dr Alan Ludowyke (Sri Lanka), and Eastern Mediterranean Region – Dr Jawad Al-Lawati (Oman).

The Bureau disseminates information to the regional coordinators who are responsible for liaising with the Parties. A previous COP meeting might mandate the Bureau to update a particular report, or set of reports, or possibly to commission a new one. This work might include the engagement of experts but should also involve consultation with the Parties via the Regional Groups to collect national data for the report.

WHO Regional Coordinators

Like the Bureau, the Regional Coordinators are elected at the COP. The Regional Coordinators observe the meetings of the Bureau and perform the following functions:

» liaise with the officer of the Bureau representing the region, and facilitate consultations with the Parties in the region between the sessions of the COP; this is done with a view to informing 5 the work of the Bureau, and keeping Parties informed of the Bureau’s work;

» receive working documents or proposals of the Bureau, and ensure they are circulated to the Parties in the region;

» collect and send comments on such documents or proposals to the officer of the Bureau;

» act as a channel for the exchange of information, including a copy of invitations to the meetings for the implementation of the Convention, and coordination of activities with other regional coordinators.

The current Regional Coordinators are: Africa Region – Mr Theophile Olivier Bosse (Cameroon), Americas Region – Ms Kemba Anderson-Golhor (Canada), Eastern Mediterranean Region – Dr Baseer Achakzai (Pakistan), European Region – Dr Peyman Altan (Turkey), South-East Asia Region – Dr Chayanan Sittibusaya (Thailand), Western Pacific Region – Dr Nor Aryana Hassan (Malaysia).[xi]

How do COP meetings function?

The meeting opens with the adoption of the agenda, followed by a plenary session which is an introduction to the COP, focused on the theme of the session and statements from the Parties on the global progress on the implementation of the FCTC. The meeting then breaks into two groups where the main business is conducted. Committee A deals with policy matters and Committee B with administrative matters, including funding.

All reports due for consideration at the COP must be made publicly available sixty days before the meeting. Committee A will consider the reports that have been submitted, sometimes with a draft decision note attached. A discussion will then take place to consider both the report and, if attached, the draft decision. If there is no existing draft decision note, one will be drawn up and discussed in the room. If nobody objects to either the report or the draft decision, then that becomes COP policy.

However, if even just one country raises an objection then another round of discussion takes place, perhaps to change the wording of the decision. There can be several iterations of this process until the objection is withdrawn. Failing that, the meeting chair might ask Committee B to consider the issue or simply push it through on the basis that one objection cannot be allowed to hold up the process.

If several countries lodge objections which cannot be resolved, the chair can call for a drafting group to be set up to resolve differences. These drafting groups meet outside working hours of the COP sessions, without translation, and under the leadership of a Party that takes the role of the chair.

At the start of each day, the Regional Groups meet to discuss the day’s agenda including whatever decision has emerged from drafting groups. There can be considerable pressure at this point to convince continuing dissenters to fall into line, including comments in the daily COP bulletin.

Which non-state observers are present at the COP?

A number of international intergovernmental organizations (IGO) have observer status,[xii] such as the World Bank Group and the International Labour Organization.

The Preamble to the FCTC recognises the “special contribution of non-governmental organizations and other members of civil society…to tobacco control efforts nationally and internationally…”. Applications by NGOs for observer status[xiii] are processed by the FCTC Secretariat which makes recommendations and are decided by the COP. A list of accredited NGOs can be found here.[xiv]

Smaller civil society anti-tobacco organisations can participate as members of the NGO tobacco control umbrella body, formerly known as the Framework Convention Alliance (FCA) but now rebranded as the Global Alliance for Tobacco Control (GATC).[xv] To date, NGO membership of the Alliance has only been granted to those organisations which agree with the prevailing tobacco control consensus.

Observer status and Alliance membership are only open to those with no connections to the tobacco industry, however tangential or historical.

To date, no advocacy groups representing people directly affected by tobacco control measures have been considered eligible for observer status or membership of the Alliance. This includes independent groups representing people who smoke and users of safer nicotine products.

The closed nature of the COP meetings

Members of the media must apply for accreditation no less than 60 days before the meeting and declare that they have no financial, employment or professional relationships with the tobacco industry or any entity working to pursue its interest.

When the FCTC was being negotiated (2000–2003), and at the first three COP meetings, the public gallery was open so that anyone could witness the deliberations. Over time, the general public and the media have been excluded from all but the opening day plenary, by a decision of the Parties. The proceedings are not publicly streamed or shown for subsequent viewing, with the exception of the virtual meeting in 2021, when the opening and closing sessions were broadcast, and with the pre-recorded statements from Parties and observers available online.[xvi]

The level of secrecy and control around the COP would be unacceptable to Parties to other conventions.[xvii] It differs from the way other UN agency meetings are conducted, including the Commission on Human Rights, the Commission on Narcotic Drugs, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) and the COP meeting on Climate Change. The meetings of these Conventions facilitate the engagement of numerous civil society organisations and affected groups: for example, the COP on Climate Change has given observer status to 3,024 NGOs and 154 IGOs, whereas the FCTC COP has given observer status to 26 NGOs and 28 IGOs.

The funding for the FCTC COP relies on public money donated by the Parties. It follows that there needs to be public accountability and transparency. At present, this is lacking. The absence of transparency at the COP needs to be raised with government accountability departments.

How to engage with the COP

As will be apparent from the structure and process regarding the COP meeting, there are very few opportunities for organisations outside of the COP structure to follow and contribute to the proceedings.

The COP business and decisions are the responsibility of the Parties. Nationally, the lead for COP business will usually be the Ministry of Health and sometimes other Ministries with competence to deal with related topics. A list of the delegates from the previous COP meeting, COP 9, can be found here. [xviii] It is likely many of the same people will be attending COP 10.

Organisations can make direct approaches to ministry officials responsible for tobacco control, or via parliamentarians. Parliamentarians are often unfamiliar with the significance of the COP meetings and of their government’s position on FCTC issues, and organisations can brief them on key issues.

Each country has a focal point contact who liaises between the FCTC Bureau and the national government. The country focal point can be found here: select a country from the drop-down menu, click on the 2020 report and the focal point can be found on page 1.[xix] The focal point can be used as a conduit to make representations to government on FCTC tobacco control issues, and asked what current plans and proposals are being communicated between the FCTC Bureau and the government about the COP meeting.

Organisations can also make their views known to those IGOs and NGOs with observer status.

The mainstream media are not well-informed about the FCTC and the COP and can be alerted to the significance of issues discussed at the meeting.

Organisations can also engage the FCTC Secretariat on social media via @FCTCofficial, and during the event, via #COP10 and #COP10FCTC.

The COPWATCH website https://copwatch.info/ provides updates on issues before and during the COP.

Likely discussions at COP 10 regarding safer nicotine products

The Agenda for COP 10 will not be known until 60 days prior to the meeting. However, the Agenda is very much driven by the discussion of reports requested at previous COPs, and potential new proposals presented by the Parties. The COP Bureau is responsible for preparing the agenda.

Several deferred agenda items relate to safer nicotine products (SNP) such as nicotine vapes (e-cigarettes), snus, nicotine pouches and heated tobacco products. These include the ‘Comprehensive report on research and evidence on novel and emerging tobacco products, in particular heated tobacco products’,[xx] the report on ‘Challenges posed by and classification of novel and emerging tobacco products’[xxi] and the ‘Progress report on technical matters related to Articles 9 and 10 of the WHO FCTC (Regulation of contents and disclosure of tobacco products, including waterpipe, smokeless tobacco and heated tobacco products)’.[xxii]

Potential areas affecting SNP might be calls for tighter regulation or bans on open and customizable systems for vapes, bans or restrictions on flavours that are said to appeal to minors, a restriction on nicotine salts, and a redefinition of ‘smoke’ which might classify the aerosols from heated tobacco products as smoke.

There are some other areas of potential discussion at COP 10 relevant to SNP including expanding the definition of tobacco products, extending controls on tobacco advertising and promotion to ban or restrict online sales of SNP, encouraging ‘tobacco endgame strategies’ such as nicotine reduction, reduction of points of sale, or generational bans on purchase of tobacco products, human rights, and discussion on the civil and criminal liability of manufacturers.

For further information about the Global State of Tobacco Harm Reduction’s work, or the points raised in this GSTHR Briefing Paper, please contact [email protected]

This publication is an update on a previous GSTHR Briefing Paper from October 2021: The Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) Conference of the Parties (COP): an explainer

About us: Knowledge·Action·Change (K·A·C) promotes harm reduction as a key public health strategy grounded in human rights. The team has over forty years of experience of harm reduction work in drug use, HIV, smoking, sexual health, and prisons. K·A·C runs the Global State of Tobacco Harm Reduction (GSTHR) which maps the development of tobacco harm reduction and the use, availability and regulatory responses to safer nicotine products, as well as smoking prevalence and related mortality, in over 200 countries and regions around the world. For all publications and live data, visit https://gsthr.org

Our funding: The GSTHR project is produced with the help of a grant from the Foundation for a Smoke-Free World, a US non profit 501(c)(3), independent global organization. The project and its outputs are, under the terms of the grant agreement, editorially independent of the Foundation.

[i] World Health Organization. (2003a). WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, updated reprint 2004, 2005. World Health Organisation. https://fctc.who.int/who-fctc/overview.

[ii] World Health Organization. (2003b). WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, updated reprint 2004, 2005 (full text). World Health Organisation. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/42811/9241591013.pdf;jsessionid=B3ED8F 2675DC120D9C5E70F95D42F821?sequence=1.

[iii] Treaty instruments. (2013, 2014, 2017). WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. https://fctc.who.int/who-fctc/overview/treaty-instruments.

[iv] Parties. (2021, March 3). WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. https://fctc.who.int/who-fctc/overview/parties.

[v] Secretariat of the WHO FCTC. (2007). WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. https://fctc.who.int/secretariat.

[vi] WHO FCTC knowledge hubs. (2014). WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. https://fctc.who.int/coordination-platforms/knowledge-hubs.

[vii] WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. (2021a). Comprehensive report on research and evidence on novel and emerging tobacco products, in particular heated tobacco products, in response to paragraphs 2(a)–(d) of decision FCTC/COP8(22) [Conference of the Parties to the WHO Framework Convention On Tobacco Control. Ninth session. Geneva, Switzerland, 8–13 November 2021. Provisional agenda item 4.2.]. UN Tobacco Control. https://untobaccocontrol.org/downloads/cop9/main-documents/FCTC_COP9_9_EN.pdf.

[viii] WHO Study Group on Tobacco Product Regulation. Report on the scientific basis of tobacco product regulation: Seventh report of a WHO study group. (No. 1015; WHO Technical Report Series). (2019). World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/329445/9789241210249-eng.pdf.

[ix] WHO Tobacco Laboratory Network (TobLabNet). (2022). World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/groups/who-tobacco-laboratory-network.

[x] Bureau of the Conference of the Parties. (2023). WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. https://fctc.who.int/who-fctc/governance/bureau-of-the-conference-of-the-parties.

[xi] Bureau of the Conference of the Parties, 2023.

[xii] International intergovernmental organizations accredited as observers to the COP. (2023). WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. https://fctc.who.int/who-fctc/governance/observers/international-intergovernmental-organizations.

[xiii] Observers to the Conference of the Parties. (2023). WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. https://fctc.who.int/who-fctc/governance/observers.

[xiv] Nongovernmental organizations accredited as observers to the COP. (2023). WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. https://fctc.who.int/who-fctc/governance/observers/nongovernmental-organizations.

[xv] Global Alliance for Tobacco Control. (2022, January 25). NCD Alliance. https://ncdalliance.org/global-alliance-for-tobacco-control.

[xvi] WHO FCTC Secretariat. (2023). YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/@whofctcsecretariat812/videos.

[xvii] Bates, C. (2021, November 8). The WHO tobacco control treaty meetings are closed bubbles of cultivated groupthink – a comparison with the UN climate change treaty. The Counterfactual. https://clivebates.com/the-who-tobacco-control-treaty-meetings-are-closed-bubbles-of-cultivated-groupthink-a-comparison-with-the-un-climate-change-treaty/

[xviii] WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. (2021b, November 8). List of participants. Ninth Session of the Conference of the Parties to the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, Geneva, Switzerland. https://untobaccocontrol.org/downloads/cop9/additional-documents/COP9-List-of-Participants.pdf.

[xix] WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. (2016). WHO FCTC Implementation Database [Reports]. UN Tobacco Control. https://untobaccocontrol.org/impldb/.

[xx] WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, 2021a.

[xxi] WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, Convention Secretariat. (2021). Challenges posed by and classification of novel and emerging tobacco products [Conference of the Parties to the WHO Framework Convention On Tobacco Control. Ninth session. Geneva, Switzerland, 8–13 November 2021. Provisional agenda item 4.2.]. UN Tobacco Control. https://untobaccocontrol.org/downloads/cop9/main-documents/FCTC_COP9_10_EN.pdf.

[xxii] WHO. (2021). Progress report on technical matters related to Articles 9 and 10 of the WHO FCTC (Regulation of contents and disclosure of tobacco products, including waterpipe, smokeless tobacco and heated tobacco products) [Conference of the Parties to the WHO Framework Convention On Tobacco Control. Ninth session. Geneva, Switzerland, 8–13 November 2021. Provisional agenda item 4.2.]. UN Tobacco Control. https://untobaccocontrol.org/downloads/cop9/main-documents/FCTC_COP9_8_EN.pdf.