Burning Issues - Introduction

Harm reduction refers to a range of pragmatic policies, regulations and actions which either reduce health risks by providing safer forms of products or substances, or encourage less risky behaviours. Harm reduction does not focus primarily on the eradication of products or behaviours.

Consider road safety. Many countries now have rules about wearing seat belts. Modern cars are designed with airbags which protect us in the event of a crash. Riders in many countries are required to wear cycle or motorbike helmets. Roads have speed limits. We don’t ban cars and bikes in case they cause harm to us or others. We adopt these measures to reduce harm, although they are called ‘health and safety’ rather than ‘harm reduction’.

In the context of this report, harm reduction has a more important aspect: a role in championing social justice and human rights for people who are often among the most disadvantaged, stigmatised and marginalised in society.

Advocates for harm reduction argue that people should not forfeit their rights to health if they are undertaking potentially risky activities like drug or alcohol use, sexual activity or smoking.

This more political dimension to harm reduction grew out of the HIV/AIDS epidemic of the 1980s. At-risk and marginalised members of the gay and drug-using communities in the US and Europe acted in support of their own right to health, providing condoms and sterile injecting equipment to their communities in advance of more official interventions and endorsements at both a national and (eventually) at an international level.

The public health impact was undeniable; those countries who embraced harm reduction saw significant falls in HIV rates among affected communities. High risk populations benefited, but so too did the general population.

While the campaign to encourage the spread of drug harm reduction interventions globally is far from won, many countries have now accepted the validity of the approach. Many people who use drugs can now access opioid substitute therapy, needle and syringe programmes and overdose prevention facilities (or drug consumption rooms). Making these interventions available helps combat drug-related disease and risk of overdose, as well as helping preserve the lives of individuals who may be contemplating leaving drug use behind – or who can at least live better with it.

When applied in a social justice context, harm reduction responses should:

- Be pragmatic, accepting that substance use and sexual behaviour are part of our world and choosing to work to minimise harmful outcomes rather than simply ignore or condemn them.

- Focus on and target potential harms rather than trying to eradicate the product or the behaviour.

- Be non-judgemental, non-coercive and non-stigmatising.

- Acknowledge that some behaviours are safer than others and offer healthier alternatives.

- Facilitate changes in behaviour by provision of information, services and resources.

- Ensure that affected individuals and communities have a voice in the creation of programmes and policies designed to serve them; encapsulated in the slogan, “Nothing about us without us”.

- Recognise that the realities of poverty, class, racism, social isolation, and other social inequalities affect people’s vulnerability and capacity for dealing with health-related harms.1

While harm reduction as a social movement is relatively new, what affected communities have always been fighting for – the right to health, with nobody left behind – has long been enshrined in international conventions and continues to be so. Harm reduction sits at the intersection between public health and human rights.

Support for THR spans the political spectrum. Libertarians abhor the heavy-handed intrusion of government into the lives of smokers wishing to switch to safer products by the imposition of legislative obstacles. Supporters of social justice are very conscious that the main victims of opposition to THR are the disadvantaged – those on low incomes, people struggling with mental illness or alcohol and drug problems, homeless people, indigenous groups and prisoners. The universal right to health is just that – health for everyone.

From the early 1980s, medical interventions were available to reduce smoking – nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) and prescription medicines often used in combination with behavioural therapy as part of formal smoking cessation programmes. The advent of vaping devices in the mid-2000s opened up new public health possibilities, affording prominence to other smokeless products such as Swedish snus and US smokeless as part of a new THR paradigm.

Most smokers say they want to stop smoking (or at least wish they wanted to stop). Many quit smoking by gradually reducing or going ‘cold turkey’, with various rates of success. As Mark Twain said, “Giving up smoking is the easiest thing in the world. I know because I’ve done it thousands of times”. Many though find it hard to stop as they are unable or unwilling to give up nicotine and stick with the combustible cigarette – one of the most dangerous of all nicotine delivery systems.

Harm reduction products have greatly expanded the choice for consumers who wish to continue to enjoy nicotine without the risks inherent in cigarettes or who are looking for a more acceptable way to quit smoking than provided by various medical and psychosocial approaches. Quitting smoking using SNP is pleasurable for most smokers rather than burdensome. It also provides government with an additional tool to replace harms from smoking alongside measures to reduce supply and demand such as tobacco taxes, age restrictions, advertising restrictions and bans on smoking in public places.

The technological advances in nicotine delivery have been accompanied in some countries by developments and changes in the profile of manufacturers and distributors, product innovation, investment in research and development, and a market driven by product availability and consumer choice. This, in turn, has raised challenges for governments in terms of appropriate regulatory models, resulting in conflicts between the aims of international tobacco control and the individual right to health.

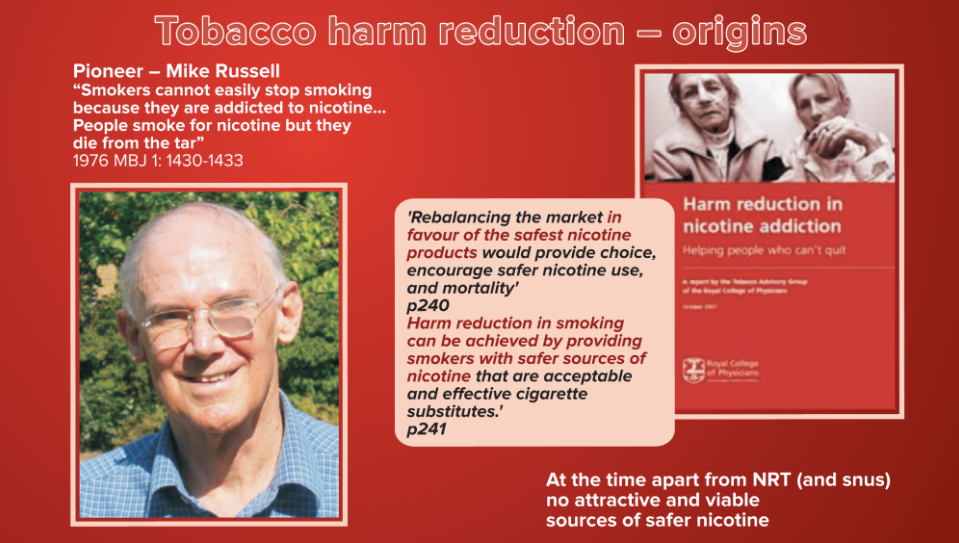

Professor Michael Russell – consultant psychiatrist, Institute of Psychiatry, London

“The case is advanced for selected nicotine replacement products to be made as palatable and acceptable as possible and actively promoted on the open market to enable them to compete with tobacco products. There will also need to be health authority endorsement, tax advantages and support from the antismoking movement if tobacco use is to be gradually phased out altogether.

It is essential for policymakers to understand and accept that people would not use tobacco unless it contained nicotine and that they are more likely to give it up if a reasonably pleasant and less harmful alternative source of nicotine is available. It is nicotine that people cannot easily do without, not tobacco.

It will be assumed … our main concern is to reduce tobacco-related diseases and that moral objections to the recreational and even addictive use of the drug can be discounted providing it is not physically, psychologically or socially harmful to the users or to others.” 2

The starting point for all should be the global epidemic of smoking – which is the subject of the next chapter.

-

Principles of Harm Reduction. (n.d.). Harm Reduction Coalition. Retrieved 23 August 2020, from

https://harmreduction.org/about-us/principles-of-harm-reduction/ -

Russell, M.A.H. (1991). The future of nicotine replacement. British Journal of Addiction, 86(5), 653–658.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01825.x