The politics of health: SNP regulation and control

The arrival of SNP has caused disruption to the tobacco industry, to the certainties of decades-old tobacco research and to the uncontested ‘heroes and villains’ narrative of anti-tobacco campaigners. That uncertainty has also unnerved governments around the world left to play catch-up as to the most appropriate legislative responses.

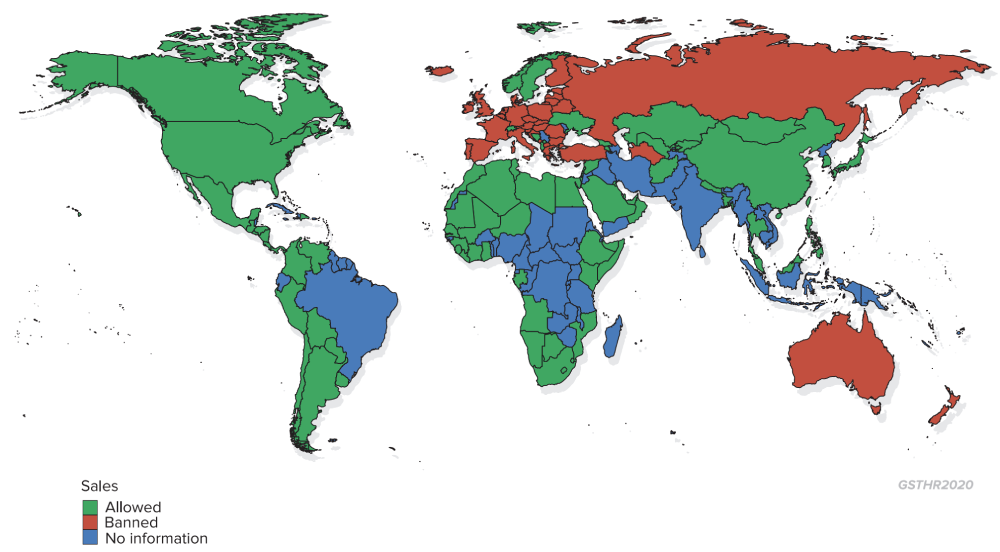

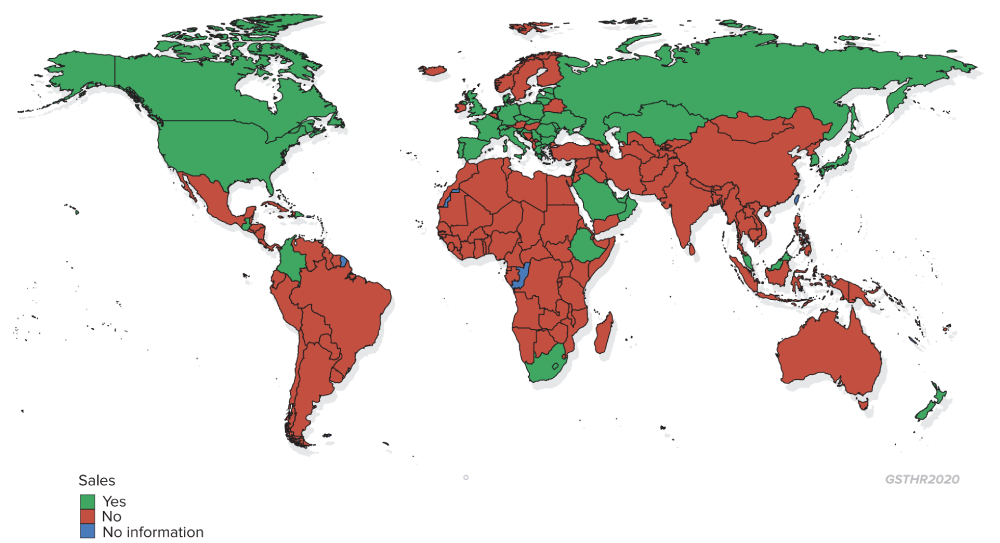

Most countries have no specific legislation in place regarding SNP. In others, SNP have been folded into existing tobacco legislation, regulated as medicinal products or simply outlawed, leaving the most damaging combustible nicotine products legally available.

| 36 countries ban the sale of nicotine vaping products | Antigua and Barbuda, Argentina, Australia, Bhutan, Brazil, Brunei, Cambodia, Colombia, East Timor, Egypt, Ethiopia, Gambia, India, Iran, Japan, North Korea, Kuwait, Lebanon, Mauritius, Mexico, Nepal, Nicaragua, Oman, Panama, Qatar, Seychelles, Singapore, Sri Lanka, Suriname, Syria, Thailand, Turkey, Turkmenistan, Uganda, Uruguay, Venezuela |

| 1 country bans the sale of tobacco* | Bhutan |

| 75 countries regulate the sale of nicotine vaping products | Austria, Azerbaijan, Bahrain, Barbados, Belarus, Belgium, Bulgaria, Canada, Chile, China, Hong Kong, Costa Rica, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Ecuador, El Salvador, Estonia, Fiji, Finland, France, Georgia, Germany, Greece, Honduras, Hungary, Iceland, Indonesia, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Ivory Coast, Jamaica, Jordan, South Korea, Laos, Latvia, Liechtenstein, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Macedonia, Malaysia, Maldives, Malta, Moldova, Netherlands, New Zealand, Nigeria, Norway, Palau, Paraguay, Philippines, Poland, Portugal, Romania, San Marino, Saudi Arabia, Senegal, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Taiwan, Tajikistan, Togo, Tunisia, Ukraine, UAE, UK, US, Vietnam |

| 85 countries have no specific laws or regulations on nicotine vaping products | Afghanistan, Albania, Algeria, Andorra, Angola, Armenia, Bahamas, Bangladesh, Belize, Benin, Bolivia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Botswana, Burkina Faso, Burma (Myanmar), Burundi, Cameroon, Cape Verde, Central African Republic, Chad, Comoros, Congo, Democratic Republic of Congo, Cuba, Djibouti, Dominica, Dominican Republic, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, French Guiana, Gabon, Ghana, Grenada, Guatemala, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Guyana, Haiti, Iraq, Kazakhstan, Kenya, Kiribati, Kosovo, Kyrgyzstan, Lesotho, Liberia, Libya, Madagascar, Malawi, Mali, Mauritania, Monaco, Mongolia, Montenegro, Morocco, Mozambique, Namibia, Nauru, Niger, Pakistan, Palestine, Papua New Guinea, Peru, Russian Federation, Rwanda, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Samoa, Sao Tome and Principe, Sierra Leone, Solomon Islands, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Swaziland, Tanzania, Tonga, Trinidad and Tobago, Tuvalu, Uzbekistan, Vanuatu, Yemen, Zambia, Zimbabwe |

* Bhutan temporarily lifted the ban on tobacco sales from August 2020, the date of recommencement is uncertain.

Since our last report, the already-significant challenges of dealing with the global smoking epidemic have been further undermined by the increasingly prohibitionist approach and rhetoric of several countries, especially those in LMIC. Despite this, the number of countries with bans has decreased from 39 to 36 since our last report in 2018.

Changes in the legal status of nicotine vaping products between 29 September 2018 and 1 July 2020

| From banned to allowed | Bahrain, Jordan, Malaysia, Saudi Arabia, UAE |

| From no specific law to allowed | Azerbaijan, Belarus, Chile, El Salvador, Georgia, Israel, Ivory Coast, Laos, Macedonia, Maldives, Senegal, Serbia, Switzerland, Tajikistan, Tunisia, Ukraine, Hong Kong |

| From allowed to banned | India, Kuwait, Turkey |

| From no specific law to banned | Iran |

The number of countries which ban nicotine

vaping products has decreased from

39

to

36

since in 2018.

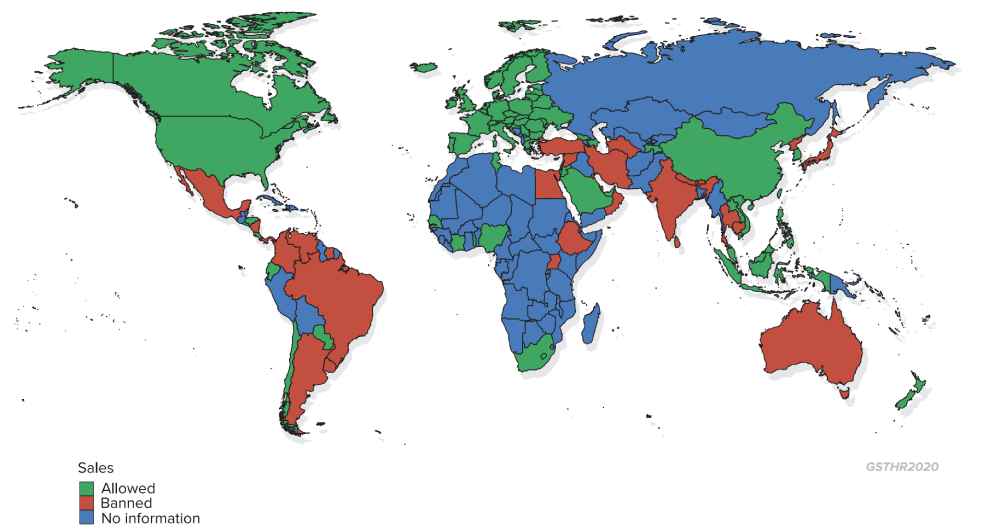

The number of countries in which HTP are marketed has increased from 2018 and they are now sold in 51 countries. The number of countries allowing the sale of snus has remained about the same since 2018.

| 51 countries where HTP are marketed | Andorra, Armenia, Austria, Bahrain, Bulgaria, Canada, Colombia, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Dominican Republic, Estonia, Ethiopia, France, Germany, Greece, Guatemala, Israel, Italy, Japan, Kazakhstan, Korea, South, Kuwait, Latvia, Lithuania, Macedonia, Malaysia, Moldova, Monaco, Netherlands, New Zealand, Oman, Palestine, Poland, Portugal, Qatar, Romania, Russian Federation, Saudi Arabia, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia, South Africa, Spain, Switzerland, Taiwan, Ukraine, UAE, UK, US |

| 13 countries ban the sale of HTP | Australia, Ethiopia, India, Iran, Malta, Norway, Panama, Singapore, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Turkey, Turkmenistan, Mexico (ban on sale and import of tobacco heating device only – HTP consumables are considered tobacco products regulated by the existing Tobacco Law). |

| 81 countries allow the sale of snus | Afghanistan, Albania, Algeria, Angola, Argentina, Armenia, Bahamas, Bangladesh, Barbados, Bolivia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Botswana, Canada, Chile, China, Hong Kong, Colombia, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, Egypt, El Salvador, Ethiopia, Gabon, Gambia, Georgia, Ghana, Guatemala, Guinea, Honduras, Israel, Ivory Coast, Japan, Kazakhstan, Kenya, Korea, South, Kosovo, Kuwait, Kyrgyzstan, Lebanon, Lesotho, Liberia, Libya, Malaysia, Mali, Mauritania, Mauritius, Mexico, Mongolia, Morocco, Mozambique, Namibia, Nepal, Nicaragua, Niger, Norway, Oman, Palestine, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Philippines, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Somalia, South Africa, Swaziland, Sweden, Switzerland, Syria, Taiwan, Thailand, Trinidad and Tobago, Tunisia, Ukraine, UAE, US, Uruguay, Uzbekistan, Venezuela |

| 39 countries ban the sale of snus | Australia, Austria, Bahrain, Belarus, Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Liechtenstein, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Macedonia, Malta, Montenegro, Netherlands, New Zealand, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Russian Federation, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Turkey, Turkmenistan, UK, Vanuatu |

For country specific detail, see the GSTHR website www.gsthr.org.

Tobacco control regulation is enacted at international, regional and national level. Within countries with semi-autonomous federations and states, such as the US, Canada and Australia, slightly different rules and regulations apply between individual jurisdictions and between jurisdictions and the central government.

WHO FCTC and the Conference of the Parties (COP)

The Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) was the world’s first WHO international health treaty and came into force in 2005, setting a framework for countries to construct their own tobacco control policies, particularly those LMIC who do not have the necessary resources to formulate their own policies from scratch. It is generally accepted that there needs to be regulations to control the sale and marketing of cigarettes, the places where people can smoke and access to cigarettes by young people. The problems with the implementation of the FCTC and its guidelines arise from the arrival of the newer SNP which came onto the market after 2005.

The newer SNP came onto the market after the FCTC came into force in 2005.

Funding from Bloomberg has enabled the CTFK to expand its role internationally – for example, by advising LMIC on SNP controls. The CTFK knows that many countries do not have specific regulations about SNP. They also know that many countries have not fully implemented the FCTC and may not do so in the foreseeable future. Their advice (and that of The Union209 and the WHO TFI) is for countries to totally ban SNP until or unless they have fully implemented the Convention, and then to regulate SNP as if they were combustible products. Current smokers in those countries who follow this advice may have limited chances of legal access to SNP.210

In what might be described as neo-colonialism, CTFK and other influential NGOs have a track record of interfering in signatory countries’ business, going back to the negotiations leading up to the introduction of the FCTC.

Greg Jacob was a constitutional law expert at the UN Department of Justice Office of Legal Counsel and a member of the US delegation involved in the final stages of the FCTC negotiations in Geneva during 2003. The following year, he published an article in the Chicago Journal of International Law in which he slammed the FCTC negotiations as a “train wreck” and a “deeply flawed process”.211

As this was the first time the WHO had been involved in drafting an international health treaty, many of the delegates were health minsters, several of whom were doctors. But while they knew much about the health effects of smoking, they knew nothing about international law and the process of treaty negotiations – neither, incidentally, did WHO officials. Into the breach, wrote Jacob, came US NGOs, primarily ASH and CTFK, who banded together to form the Framework Convention Alliance (FCA) of WHO-‘approved’ anti-tobacco NGOs. He described how this influence played out:

“…the NGOs certainly did not act as disinterested legal advisers, and along the way more than one delegation was hoodwinked into believing the NGOs’ alltoo- frequently distorted versions of the truth.”

Nor were they above believing, like all moral entrepreneurs, that the ends justified the means; Jacobs said he was followed all over the building by NGO representatives trying to listen in on his phone calls and taking notes.

There was another aspect to the negotiations which disturbed Jacob, and whose impact is keenly felt today. Concerning the definition of “tobacco advertising and promotion”, it was clear to Jacob and most of the delegates in negotiating meetings that the definitions were ridiculously broad.

“It took a minor miracle just to get the word ‘commercial’ inserted into the definition of ‘tobacco advertising and promotion’, as many members of the [WHO regional groups] wanted the definition to cover non-commercial speech by actors outside the tobacco industry.”

To this day, interference is continuing with increasing ferocity in the attempt to ‘no-platform’ anybody who advocates or researches THR, who in this narrative is, by definition, an industry ‘insider’. What has become a tobacco control obsession and a major distraction from the real (and far more complex and challenging) issue of reducing smoking-related death and disease is enshrined in an obscure document – the Guidelines to treaty Article 5.3.

The Article itself reasonably exhorts parties to the treaty to be open and transparent in their dealings with the tobacco industry and not allow undue interference in policy. The Guidelines which accompany the main text however have been ludicrously overinterpreted, as shown by this recent example.

The Bloomberg-funded STOP campaign, linked to the Good Governance of Tobacco Control and the South East Asian Tobacco Control Alliance agencies, recently launched a competition for under-18 year-olds to design graphics aimed at raising awareness, with an all expenses trip to Bangkok for the winners.212 This was the Declaration of Interest Statement to which entrants were asked to agree:

Declaration of Interests

A. “INTERESTS” REFER TO ANY FINANCIAL OR NON-FINANCIAL LINKS WITH THE TOBACCO INDUSTRY, INCLUDING THROUGH EMPLOYMENT, CONSULTANCY, RESEARCH, BUSINESS, PROFESSIONAL OR PERSONAL INTERESTS, CONTRIBUTIONS OR GIFTS, FAMILY’S OR SPOUSE/PARTNER’S INTERESTS, RELATIONSHIPS UP TO THE FOURTH DEGREE OF CONSANGUINITY AND AFFINITY, AND FREQUENT OR REGULAR SOCIAL RELATIONSHIPS. (REFER TO ANNEXED CHART OF RELATIVES FOR CLARITY.)

B. “TOBACCO INDUSTRY” REFERS TO (A) ANY TOBACCO OR TOBACCO PRODUCT MANUFACTURER, PROCESSOR, WHOLESALE DISTRIBUTOR, IMPORTER , (B) ANY PARENT, AFFILIATE, BRANCH, OR SUBSIDIARY OF A TOBACCO OR TOBACCO PRODUCT MANUFACTURER, WHOLESALE DISTRIBUTOR, IMPORTER, RETAILER, OR (C) ANY INDIVIDUAL OR ENTITY, SUCH AS, BUT NOT LIMITED TO AN INTEREST GROUP, THINK TANK, ADVOCACY ORGANIZATION, LAWYER, LAW FIRM, SCIENTIST, LOBBYIST, PUBLIC RELATIONS, AND/OR ADVERTISING AGENCY, BUSINESS, OR FOUNDATION, THAT REPRESENTS OR WORKS TO PROMOTE THE INTERESTS OF THE TOBACCO INDUSTRY, INCLUDING, BUT NOT LIMITED TO THOSE LISTED IN TOBACCOTACTICS.ORG.

I DECLARE THAT, OTHER THAN THE INTERESTS DECLARED IN THE FORM BELOW, I DO NOT HAVE INTERESTS, CURRENTLY OR IN THE PAST FIVE (5) YEARS, RELATED TO THE TOBACCO INDUSTRY, AND I AM NOT KNOWINGLY REPRESENTING OR RECEIVING ANY CONTRIBUTION OR COMPENSATION, DIRECTLY OR INDIRECTLY, WHETHER FINANCIAL OR OTHERWISE, FROM THE TOBACCO INDUSTRY.

I CERTIFY THAT THE INFORMATION GIVEN ABOVE IS, TO THE BEST OF MY KNOWLEDGE, TRUE, ACCURATE, AND COMPLETE.

That phrase “the fourth degree of consanguinity” means the entrant – a teenager – has to assert no industry connections going back to their great great grandparents – or to third cousins three times removed.

Yet while the concept of THR is shunned by the WHO and all Bloomberg-funded agencies, Article 1 paragraph (d) on page 11 of the FCTC specifically says that, “‘tobacco control’ means a range of supply, demand and harm reduction [emphasis added] strategies that aim to improve the health of a population by eliminating or reducing their consumption of tobacco products and exposure to tobacco smoke.” There were no vaping products in general circulation at the time the FCTC was drawn up, but by then the WHO had recognised the public health imperative in relation to HIV and drugs and knew what harm reduction meant in those circumstances. Once SNP became widely available, there was plenty of opportunity for WHO to offer an actual definition of harm reduction through guidance in line with its application to other global health issues.

Article 1 of the FCTC states that ‘tobacco control’ means a range of supply, demand and harm reduction strategies.

SNP (or ENDS in WHO terminology) only came onto the agency’s radar about ten years ago. The COP meeting of FCTC signatory countries is held every two years. At both COP 4 (2010) and COP 5 (2012) there were some early discussions about how the new products might be regulated. At the COP 6 meeting, the WHO were asked to prepare a briefing paper for COP 7, which was delegated to the WHO Study Group on Tobacco Product Regulation (TobRegNet).

The TobRegNet report was relatively balanced. For example, paragraph 5 on the potential role of SNP in tobacco control states:

“If the great majority of tobacco smokers who are unable or unwilling to quit would switch without delay to using an alternative source of nicotine with lower health risks, and eventually stop using it, this would represent a significant contemporary public health achievement.”213

Delegates to COP7 welcomed the report and the Parties went away to consider applying regulatory measures as appropriate to their national laws and public health objectives. This is an important point – and a feature of all UN multilateral treaties. While the FCTC is ‘legally binding’, all this means in practice is that Parties have signed up to enacting controls in the spirit of custom and practice as applied to all international treaties. But aside from smuggling, tobacco control is an issue for domestic law and ultimately what passes into law remains in the gift of individual governments.

TobRegNet produced another report in 2019; it too is a reasonably balanced evidence review.214 The report refers to a much-abused concept known as the precautionary principle – meaning a cautious approach to potentially harmful innovations. In 2000, the EU Commission produced detailed guidance on achieving the balance in policymaking between rights and freedoms against reducing risks, whether to humans, animals, or the environment. The guidelines encourage political decisions to be taken for example, on the basis of proportionality, non-discrimination, a cost/benefit analysis and specifically on “examination of scientific developments”.

The precautionary principle has been over-interpreted at an FCTC political level to push for maximum controls – just to be on the ‘safe side’. However, there is nothing in the latest TobRegNet report which could be taken as a signal to FCTC parties to ramp up an increasingly prohibitionist approach to SNP. Nevertheless, there is now a widening disconnect between the tone of the scientific evidence produced within the WHO and its public-facing political rhetoric attacking THR.

In September 2019, Dr Vera Luiza da Costa e Silva, then Head of the Convention Secretariat, claimed, “Vaping is a treacherous and flavored camouflage of a health disaster yet to happen if no action is taken now’’.215

Her successor, Dr Adriana Marquizo, from Uruguay (which has already banned SNP yet is the first country in the world to legalise marijuana) stuck to the party line in this interview:

“This is an area that is very worrying, especially because of the systematic, aggressive and sustained marketing tactics employed to attract a new generation of tobacco users, through the introduction of flavours and other attractive features.”216,217

European Tobacco Products Directive (TPD)

Passed in 2001, the Tobacco Products Directive (TPD) was the first major European legislation specifically related to tobacco products. It is the only example of a regional approach to regulation. All EU member states must implement TPD into national legislation.

Nearly a decade before, the first attack on what turned out to be a significant SNP was the EU-wide ban on the sale of snus in 1992, as a response to the attempt by the US Smokeless Tobacco Company to introduce oral Skoal Bandits into the UK. When Sweden joined the EU in 1995, snus was already in widespread use there and so was exempted from the ban.

Legal status of snus

In the years subsequent to TPD enactment, EU Commission reports identified new tobacco-related products which might be controlled to ensure conformity with EU harmonisation policies, noting increasing discrepancies between member states. As the sale of vaping devices was growing throughout the EU, member states were seeking advice and clarification from the Commission. In 2012, the Health and Consumer Directorate produced a proposal for the revision of the 2001 TPD whereby products with a nicotine content over a certain level – including most vaping products on the market – would have to be authorised as medicines.

When the proposal came before the EU Parliament in 2013, numerous amendments to the Article were proposed, including one that all vaping products could only be sold as medicines under pharmaceutical regulations. Major objections from vapers via their EU political representatives helped derail this idea. In 2016, a revised TPD known as TPD2 came into force.

TPD2 regulates tobacco product manufacture, sale, distribution and advertising in the European Union covering vaping and HTP – with limitations on nicotine content and liquid bottle size – while reaffirming the ban on snus. Currently TPD2 is under review, with the report and possible proposals due out in May 2021.

In preparation for the next iteration of the TPD, input has been requested from the Scientific Committee on Health, Environmental and Emerging Risks (SCHEER).

In 2018, the EU Agency Network for Scientific Advice (ANSA) published a report looking at how EU agencies approached the issue of scientific uncertainty in their different spheres of expertise.

The report concluded that across the 12 EU agencies in the network, there were inevitable differences as to what constituted scientific uncertainty, depending on the type of data being used for scientific assessment – for example, the difference between clinical or toxicological datasets as opposed to social science population studies. Even so, agencies need to find a balance when communicating ‘truthful’ uncertainties without risking a fixed interpretation of ‘nothing is known’. “Finding this balance is a primary focus of risk communication and is of fundamental importance in all Agencies.”218

So it is a concern that SCHEER finds the right balance in presenting their opinion using all the available evidence of what is known, while not over-interpreting the precautionary principle, although the terms of reference for opinion are weighted towards risks rather than benefits:

“The assessment will address the role of vaping devices, in relation to:

- their use and adverse health effects (i.e. short- and long-term effects)

- risks associated with their technical design and chemical composition (e.g. number and levels of toxicants) and with the existing EU regulatory framework (e.g. nicotine concentration and limits)

- their role as a gateway to smoking/the initiation of smoking (particularly focusing on young people)

- their role in cessation of traditional tobacco smoking.”

The Commission is also seeking input from the research company Open Evidence which, in consortium with the London School of Economics, BDI Research and the Catalan Institute of Oncology, will conduct a product perception study. The consortium will look into:

“Consumer preference and perception of specific categories of tobacco and related products for the European Commission (DG SANTE). The study wants to analyse the consumer preferences and perceptions of consumers on 5 tobacco product categories, namely: novel tobacco products, small cigarillos, slim cigarettes, electronic cigarettes, waterpipe tobacco.

“The study will summarise the information available to date and collect quantitative and qualitative primary data to provide a holistic view of those products and their consumers”219

Scientific inputs into policymaking are often quite cautious and liberally sprinkled with caveat. The degree to which the EU Commission and member states over-interpret or cherry pick the evidence remains to be seen. But already public statements like this do not bode well:

“‘E-cigarettes may be less harmful, according to some reports, but they’re still ‘poison’,’ said Arūnas Vinčiūnas, head of cabinet of EU Health [Commission].” (EURACTIV, Feb 6, 2019).

Vinčiūnas followed up with:

“I am particularly concerned about young people taking up vaping and various new products like heated tobacco products and e-cigarettes, which are increasingly being marketed with misleading claims.” (World No Tobacco Day, 29 May 2019).

Thus the ‘mood music’ on the future for SNP within the EU is not promising. With SNP already allowed and established within the EU, it is unlikely that the review will recommend a complete ban, although there is no political interest in reversing the ban on snus. However, the banning of flavours would be a de facto ban, which would discourage smokers looking to switch away. Flavour bans are gaining popularity as a way of undermining THR. The Netherlands has already proposed a domestic Dutch flavour ban while Denmark and Belgium have signalled a similar approach. Control of flavours could well be the next global battleground in defence of THR.

It is possible there is some political push-back among FCTC signatories against complete bans, as this, in theory, would require a level of enforcement priority that might be felt to be an imposition – especially in LMIC with limited capacities and other public health priorities. However, flavour bans (and only allowing sales for medicallyapproved products) could effectively kill off much of the SNP industry, while ticking political boxes showing governments were ‘doing something’.

Control of flavours could well be the next global battleground in defence of THR.

At the Eighth European Conference on Tobacco or Health, held in Berlin in February 2020, DG SANTE, responsible for the EU Commission’s Health and Food Safety policies, recommended just such a ban. A declaration emerging from the conference urged the equalisation of tax regimes for vaping and tobacco. This could put vaping products out of the reach of many users, and could force existing users back to cheaper cigarettes – especially products derived from illegal markets.

All the indications are that the FCTC Secretariat will be pushing a prohibitionist line at the next COP and will no doubt be influenced by the outcome of the TPD review, not least because both processes share officials, highlighting the inter-connectivity and influence of one on the other. The next COP meeting will be held in the Netherlands in November 2021, six months after the report on the review of TPD 2, having been delayed for 12 months due to the COVID pandemic.

SNP: a global and national overview

Legal status of nicotine vaping products

Beyond the big picture there is a whole panoply of regulatory options covering product registration, safety and limitations (such as nicotine content, and flavour bans), taxation levels, online sales, age-purchase limitations and public space vaping. For country specific detail, see the GSTHR website www.gsthr.org.

| 64 countries have age restrictions on the sale of nicotine vaping products |

16+: Austria, Belgium, Liechtenstein 118+: Barbados, Bhutan, Brazil, Bulgaria, China, Hong Kong, Costa Rica, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Ecuador, El Salvador, Estonia, Fiji, Finland, France, Georgia, Germany, Greece, Hungary, India, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Ivory Coast, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malaysia, Maldives, Malta, Mexico, Moldova, New Zealand, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, San Marino, Senegal, Slovakia, Slovenia, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, Tajikistan, Togo, UAE, UK, US, Vietnam 19+: Canada, South Korea, Turkey 20+: Japan 21+: Ethiopia, Honduras, Palau, Philippines |

| 71 countries regulate the advertising of e-cigarettes | 34 (allowed at point of sale) 59 (not allowed in mass media) 26 (bans on all advertising) |

| 30 countries tax vaping liquid | USA: European region: Asia-Pacific: Middle-East: Africa |

For country specific detail, see the GSTHR website www.gsthr.org.

North America

US

What happens in the US tends to be a beacon for legislators in other parts of the world.

In 2009, under the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act, the FDA was granted the legislative power to regulate tobacco products and marketing for cigarettes, loose tobacco for self-rolling and smokeless products. This was extended in 2016 to include cigars, pipe tobacco, water pipes and all vaping devices.

At that point, the FDA deemed that any product not on the market before 2007 had to go through a Pre-Market Tobacco Application (PMTA). The initial deadline for non-combustible products was August 2021. A legal bid by anti-vaping organisations brought this forward to May 2020 – a date that was further revised due to COVID-19, ending up as the 9 September 2020. To make health comparisons for these products with smoking, a Modified Risk Tobacco Product Application (MRTPA) would also be required. This of course captured every type of vaping device on sale in the country. Small companies struggled to meet the onerous costs of compliance.

However, in October 2019, and in a ground-breaking move, the FDA authorised the marketing of eight Swedish Match snus products as modified risk tobacco products (MRTP). This allows the products to be marketed to consumers with the information that using the products put the user at lower risk of “mouth cancer, heart disease, lung cancer, stroke, emphysema, and chronic bronchitis” compared to smoking.221 In July 2020, the MRTP authorisation was granted to IQOS, allowing the promotion of the product as putting the consumer at lower risk than smoking. These FDA authorisations represent the first time any government has allowed the marketing of specific SNP as of lower risk than smoking.

The 2009 Act allowed state and local authorities to enact legislation in addition to, or more stringent than the Act, and since then several states have enacted variations on a theme around bans, taxation, purchase age restrictions and other regulations. Attention also focused on flavoured e-liquid which anti-vaping campaigners claim were developed deliberately to attract young people.

As far back as 2017, elected officials in San Francisco passed a flavour ban on all tobacco and nicotine products, which was later approved by voters in 2018. In June 2019, San Francisco took the additional step of banning the manufacture, distribution and sale of vaping products until they received FDA authorisation. In February 2020, a bill was passed through the US House of Representatives which would ban the sale of flavoured e-liquid and other flavoured tobacco products such as menthol cigarettes nationwide, and impose new restrictions on the marketing of vaping products. However, the Trump Administration refused to back the bill, on the basis that it “contains provisions that are unsupported by the available evidence regarding harm reduction and American tobacco use habits” and that, furthermore, the Bill “may restrict access by adult e-cigarette users to products that may provide a less harmful alternative to traditional cigarettes”.222

These FDA authorisations represent the first time any government has allowed snus or heated tobacco products to be marketed to consumers as less risky than smoking tobacco.

In September 2019, the media storm over JUUL use and lung injuries and deaths prompted the governor of Michigan to institute a temporary ban on flavoured e-liquid. Soon after, President Trump suddenly announced a proposed nationwide ban on all flavoured vape liquids sold without FDA authorisation. While other states like New York, Oregon and Washington followed with their own temporary bans (some eventually made permanent), President Trump and the FDA rethought their plan as evidence accumulated that illicit THC cartridges had been cause of injuries and deaths. In early January 2020, however, the FDA announced plans to temporarily ban flavoured pods except for menthol and tobacco flavours, while excluding the bottled e-liquids used in refillable tank systems largely favoured by regular adult consumers.

At various points over the past few years, FDA officials have made encouraging noises about tobacco harm reduction. Unfortunately, in the white heat of political and media pressure, these pronouncements have often been followed by proposals diametrically opposed to the best interests of smokers.

We outlined the FDA structures and approval processes in our 2018 report. The overall view, from market and policy analysts, was that the process for obtaining market approvals for SNP – substantial amounts of time and money to deliver proposals running into thousands of pages – would most likely be beyond the resources of all but the major tobacco companies. The independent SNP market in the US could be wiped out.

Canada

Until 2018, Canadian federal health officials had based their approach to vaping on existing laws on nicotine products which in effect made vaping products illegal. This was largely ignored by vapers and their suppliers, and there was little enforcement intervention. Then in May 2018, the Tobacco and Vaping Products Act was introduced. The Act legalised vaping and the vaping industry, allowing SNP to be sold in convenience stores and gas stations as well as vape shops. Generally, the legislation takes a relatively sensible approach to SNP; it also covers HTP, which are regarded as tobacco products. The Act is geared towards protection of young people. This means, for example, that any attempt to promote products to smokers as safer nicotine options is banned unless products receive pre-market approval under the Food and Drug Act.

However, at the time of writing, the Federal government is moving towards a more prohibitionist approach. Canadian provinces have already moved to enact more restrictive regulations; for example, Nova Scotia has capped the nicotine level per bottle of e-liquid to 20mg/ml and banned the sale of flavours, while Ontario has restricted sales of higher than 20mg/ml strengths and most flavours to vape shops only. Prince Edward Island banned sales other than in vape shops. British Columbia, Nova Scotia and Alberta are implementing a special tax on vaping products.223 However, in Canada and elsewhere, the judiciary have intervened to block anti-THR decisions. See box (top of page 126).

In Quebec, the Supreme Court overturned the state government provisions in its Tobacco Control Act 2015 which banned demonstrations of vaping devices in specialist shops and clinics and stopped the promotion of vaping aimed at those wanting to quit smoking.

This was an important development and came in the same month that saw the Swiss Federal Court overturn a ban on the import of snus, while more dangerous products are allowed. In 2018, a court in New Zealand overruled the Ministry of Health and allowed the importation of IQOS ‘heets’ arguing that if the New Zealand government’s aim was to reduce the damage of smoking, how could it justify banning a product that did just that?

Latin America

To regulate, inspect and prosecute a commercial enterprise, you need an efficient bureaucratic structure to deploy inspectors and police at a national, regional and municipal level. In many LMIC, such structures are under-developed and underfunded and may be further undermined by corrupt practices. Officials will have many competing priorities and will often act only in response to public, press and political pressure against a perceived problem.

In many Latin American countries, the vaping industry inhabits a twilight zone between legality and illegality. In such circumstances where the laws are unclear and there is a sudden public scare about vaping, precipitate action can occur. During September-November of 2019 across the region, but especially in Mexico, Brazil and Argentina, there were raids on shops and goods seized. In February 2020, there was a presidential decree in Mexico banning vaping and HTP devices.

But within the legally grey market arena, for example, a seller might have to register with the authorities to sell devices in a shopping mall. Or sellers might have to register to sell general electrical goods and sell vaping devices on the side. Vaping sellers might ply their trade from a stand in the street or from a garage. Online selling is much harder to control.

There exists a huge informal economy in Latin America. When authorities cracked down on SNP, they simply succeeded in turning the market a darker shade of grey.

There exists a huge informal economy, not just in Latin America but across the world, where goods of all kinds are traded on the edges or outside the law. When the authorities backed by campaigners in the region suddenly swing into action against THR and launch a crack-down, they simply succeed in turning the market a darker shade of grey.

Mexico

Vaping is not expressly mentioned in the General Law on Tobacco Control. The prohibition comes from an interpretation of a provision that bans non-tobacco products that resemble a tobacco product. While there are restrictions on marketing and advertising tobacco products, there are no outright smoking bans except in schools. The law provides for designated smoking areas in most locations and it appears unclear on a number of issues regarding where an individual can or cannot smoke. Mexico has nearly 7 million daily adult smokers, losing an estimated 49,000 people a year to a smoking-related disease, with overall over 1.2 million years of life lost due to premature death and disability because of smoking.224 In 2015, public health spending attributed to smoking was $81 billion (Mexican pesos).

Despite this health burden, the Mexican government banned vaping (with effect from February 2020) on the basis of a section in the existing tobacco law which prohibits “marketing, selling, distributing, exhibiting, promoting or producing any object that is not a tobacco product, which contains any of the elements of the brand or any type of design or auditory signal that identifies it with tobacco products.”

In November 2019, however, Mexico’s Supreme Court upheld a challenge to the country’s tobacco law, arguing it was too hard to sell vaping products. The court ruled the law is unconstitutional, saying it violates the rule of fair treatment. The court said that sales of vaping and similar products should be allowed “under the same conditions as products containing tobacco.” For now, the ruling does not set a nationwide precedent. It applies only to the parties who filed the appeal.225 But a review is currently pending.

The irony is that the Mexican government has put forward a proposal to legalise cannabis in an attempt to reduce the huge death toll of drug-related violence – while apparently making it harder to reduce the human cost of smoking.

The irony is that the Mexican government has put forward a proposal to legalise cannabis in an attempt to reduce the huge death toll of drug-related violence – while apparently making it harder to reduce the human cost of smoking.

Brazil

Since 2009, Brazil has banned the importation, distribution, sale and advertising of all vaping products. Despite the ban, use – including in open public spaces – is tolerated and there are more than a hundred online stores in operation. Individuals advertise and sell products through social networks like Instagram and in nightclubs, while vaping products are sold in tobacconists and in a few cases vape shops and convenience stores.

As in many countries, government agencies and medical organisations continue to mislead the public over the dangers of vaping, linking it to the VITERLI deaths in the US. Several parliamentarians have been individually proposing bills to ban or criminalise the use of vaping devices. Currently, there are multiple anti-THR bills being proposed at the federal, state and municipal levels, although the serious level of COVID-19 in the country is more of a public health priority and legislative progress is likely to be delayed.

Asia

India

After being on the slow burner for almost five years, the vaping debate in India heated up in September 2019 with the central government issuing an executive order to ban the sale and advertisement of vaping products and then enacting it into law after a contested, though largely uninformed, debate in Parliament. The ban covers the production, manufacture, import, export, transport, sale, distribution and storage, as well as advertisements, covering nicotine and non-nicotine vaping and HTP.

The usual soundbites about protecting young people were puzzling as it seems there are no published data concerning vaping among young Indians.226 Instead, the government has taken its cue from the US and chosen to ignore any evidence contradicting the anti-vaping narrative. First time offenders face a 100,000 rupee fine ($1,000) and up to a year in jail. Simply possessing a vaping device is a 50,000 rupee fine ($660) and/or up to six months imprisonment. Sixteen Indian states had already passed anti-vaping laws.

India has the second highest number of smokers globally, is a world leader in tobacco production, and has banned vaping products.

India is a world leader in tobacco production; the government has a 28 per cent stake in the India Tobacco Company and tobacco farmers are an important voting bloc for political parties, as nearly 46 million people depend on the tobacco sector in India for their livelihood. India also exports around $1bn-worth of tobacco annually.227

Notwithstanding a population of 100 million cigarette smokers and an annual death toll of over 800,000, the government appears to be paying more heed to the threat posed to its industry from the likes of Philip Morris and JUUL who had both planned to launch products in the country.228

Japan

In line with many high-income countries, Japan has seen significant declines in daily adult smoking rates, although it is behind in public smoking bans, preferring instead to have designated smoking areas. Japan toughened up laws in major cities like Tokyo ahead of the 2020 Olympic Games (now postponed until 2021), although protecting bystanders from second-hand smoke has been more driven by etiquette than legislation. Japanese smokers often carry ashtrays with them in order not to inconvenience others and to reduce litter.

Countries where heated tobacco products are marketed

Given this culture of manners regarding smoking, it might have been expected that the authorities would have taken a reasonably liberal approach to SNP. But as nicotine is listed as a poison, it means that vaping e-liquid is not allowed unless approved as a medicinal product, although devices and non-nicotine liquids are on sale. By contrast, rather than being the responsibility of the health ministry, HTP are controlled by the Ministry of Finance and are widely available. HTP devices have seen a dramatic rise in popularity among young smokers – with a consequential steep fall in cigarette sales – both because of the technological novelty and because HTP play to the culture of manners.

In Japan, HTP devices have seen a dramatic rise in popularity with a consequential steep fall in cigarette sales.

South Korea

South Korea is a tragic example of a country which has gone backwards in relation to THR. The main domestic tobacco company KT&G was a government monopoly until privatisation, since when it has pushed on with an ambitious growth plan. But with the arrival of SNP and in particular HTP, cigarette sales in South Korea went into reverse. Since smoking was banned indoors at places like restaurants and cafés in 2015, South Korea has become less tolerant of smokers. Meanwhile vaping products have been gaining popularity in the country’s $16 billion tobacco market since 2017. By June 2019, vaping products accounted for 13 per cent of South Korea’s nicotine market by sales, while for HTP, the country is currently the world’s second largest market after Japan, worth $1.7 billion.229

Unfortunately, the government has been influenced by the WHO and internal anti- THR elements – issuing warnings about SNP amid proposals to impose bans. The consequence of smokers being warned about the ‘dangers’ of vaping is that the rate of decline in cigarette sales has slowed. This can only benefit traditional cigarette companies and a government more concerned about falling tax revenue or damage to a domestic tobacco industry or both. Of course, this is a consequence of a more prohibitionist approach to SNP not limited to South Korea.

Korea is a tragic example of a country which has gone backwards in relation to THR.

Philippines

Vaping products are regulated by the Department of Health (DOH) and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) under “Rules and Regulations on Electronic Nicotine Delivery System (ENDS) or Electronic Cigarettes” issued in March 2014.230

Backed by influential NGOs like Health Justice and the Bloomberg-supported Southeast Asia Tobacco Control Alliance (SEATCA), health officials have consistently warned the public against “the adverse health effects and safety concerns associated with the use of e-cigarettes.” According to the DOH, e-cigarettes contain “harmful chemicals…such as nicotine, ultra-fine particles, carcinogens, heavy metals, and volatile organic compounds.” The agency cited “peer-reviewed studies”, which showed that “e-cig juices contain high levels of addictive nicotine, which can result in acute or even fatal poisoning through ingestion and other means.” The DOH claimed that there are “documented cases of nicotine toxicity in children of epidemic proportion” in “other countries with increasing prevalence of e-cigarette use” and that vapour contains harmful substances that can affect bystanders.

On 1st October 2019, a local court issued an injunction ordering the DOH and FDA not to implement an order that would have imposed restrictive regulations on vaping products. Set to take effect at the end of October, the order classified e-liquid refills as hazardous substances and the electronic delivery system as a health product. The order also sought to limit nicotine content of vaping products to 2 per cent and the amount of e-liquid in a container to 10 ml. There would be a ban on any form of advertising for vaping products and a ban on flavours for vaping products together with a ban on products falling within Category 1 and 2 of the Global Harmonized System (“GHS”) labelling system;231 and the requirement of a License to Operate (LTO) and marketing authorisations for retailers and manufacturers before they can deal in vaping products. The case was no longer pursued after President Duterte threatened court judges not to interfere with his ‘vape ban’.232

In November 2019, President Duterte issued a verbal order banning the use of vaping devices in public places and directing the police to apprehend individuals caught vaping in public places. The order was prompted by the outbreak of VITERLI cases in the US and an alleged case in Cebu City. Although possessing a device was not a crime, the Philippine National Police confiscated at least 250 vaping devices across the Central Visayas, with 100 of them in Cebu City. According to news reports, some police officers even knocked on doors of vapers to confiscate their devices. An import ban was also imposed.

President Duterte threatened court judges not to interfere with his ‘vape ban’.

President Rodrigo Duterte of the Philippines

On December 18, 2019, Congress ratified the amended Sin Tax Law, increasing excise taxes on e-cigarettes effective from 1st January 2020. The tax rates for freebase e-liquids have been set at 45 per cent in 2020 rising to 60 per cent in 2023. For nicotine salts, tax rates rise from 37 per cent in 2020 to 52 per cent in 2023. Only plain tobacco or plain menthol flavours are allowed for sale. The legal age to buy vapour products in the Philippines is 21 years old.

As the case against the order collapsed, as of February 2020, all e-liquid solutions and vaping devices have to be registered with the FDA. Firms must also secure a license from the FDA before they can be operational. The sale, manufacture, marketing, distribution and importation of unregistered electronic nicotine devices and other novel tobacco products are banned, citing serious health threats to those who are exposed to the “smoke” (vapour).

The use of unregistered vaping devices in public and enclosed spaces is prohibited. A new order aligned public vaping bans with existing smoking bans covering smoking of cigarettes in enclosed areas such as schools, elevators and stairwells, fire hazard locations and medical facilities.

In April 2020, the DOH appealed to smokers and vapers to stop immediately since they were perceived to be at a higher risk of contracting COVID-19. SEATCA also advised the public that the ongoing pandemic would be the best time to quit smoking and/or vaping.

Oceania

New Zealand

Until recently, vaping products were banned unless medically approved. Increasingly though, the government has taken more of a harm reduction approach. In 2017, the Ministry of Health released a statement on vaping products which concluded that:

“Expert opinion is that vaping products are significantly less harmful than smoking tobacco but not completely harmless…Smokers switching to vaping products are highly likely to reduce their health risks and for those around them.”233

The government stated publicly that vaping products could be valuable tools in helping the country go smoke free by 2025.

The government has introduced new legislation focused on SNP, although it has not quite delivered on the promise indicated in previous THR-supporting statements. Nonetheless, proposals have been generally welcomed by consumer activists especially, unlike the EU TPD, as there is no limit on nicotine content, or liquid quantity per bottle. At the time of writing, the Bill is going through the parliamentary process.234

The main points of the Smoke-free Environment and Regulated Products (Vaping) Amendment Bill amending the Smoke-free Environments Act 1990 are:

- Sale of all products aged restricted at 18.

- Advertising and sponsorship prohibited.

- Vaping and heated tobacco use prohibited in smoke-free areas such as indoor workspaces.

- Online sales allowed.

- Product notification system to be introduced.

- Only tobacco, mint and menthol flavours to be sold at generic retailers (supermarkets, convenience stores etc). Specialist vape retailers can sell other flavours.

- Generic retailers are not able to display or advise on a product.

- Specialist vape retailers can display, advise, make recommendations, and demonstrate products where vaping is also allowed and sellers can provide giveaways, discount or loyalty points. All this is forbidden to generic sellers.

Australia

Despite some green shoots of support from medical associations, Australian federal and state governments remain implacably opposed to changing the laws in order to promote tobacco harm reduction. The country was a leading light in anti-smoking campaigns of the past, was the first country to introduce plain packaging and is home to some of the more virulent anti-THR activists.

At a federal level, devices are legal to buy, but not liquids containing nicotine, which is regulated as a poison and only available on prescription, the exception being NRT products. The government announced in June a ban on all imported vaping products containing nicotine with a potential fine of AUS$220,000 for personal use of imported products (nearly three times the average national salary) although at the time of writing, the proposal is under review.

The regulations across the states follow the same federal tack wherein pretty much everything to do with the sale, advertising and use of SNP is banned, although there are some anomalies. For example, in Western Australia vaping is allowed in smoke-free areas, but anybody arrested for possession of nicotine without a prescription faces the highest fine of any state set at AUS$45,000 ($33,000). In the Northern Territories, you can go to prison for a year for unauthorised possession, but there are no restrictions on advertising, sales to minors of non-nicotine liquid or places where you can vape.

There has been a significant amount of media discussion on the dangers of a growing market in illegal cigarettes as a consequence of rising taxation with little sign that taxation is actually reducing smoking among the poorest in society, rather than pushing them towards illegal and cheaper alternatives. However, none of this is having any impact on policy debates as to how liberalising the laws on THR might both improve health and damage the illicit cigarette market.

While domestic rules might be strict, policing internet sales is a very different matter: a significant number of consumers are buying unregulated products from nearby markets in Asia. This lack of regulation puts the estimated quarter of a million Australian SNP consumers at risk.

Africa

SNP have yet to make significant inroads into Africa and few countries have specific laws relating to sale, use etc. Vaping devices are sold in Nigeria for example, though priced at a level that puts them out of many people’s reach.235 Vaping is usually allowed in special designated smoking areas. Uganda banned SNP in 2015, while Kenya is the only country in Africa to tax e-cigarettes.236

South Africa has the most developed SNP market worth an estimated R1 billion ($58m) and supporting around 4,000 full time jobs.237 In 2018, the government introduced The Control of Tobacco and Electronic Delivery Systems Bill with some of the toughest anti-smoking laws in Africa and making no distinction between cigarettes and SNP, including an attempt to legislate against tobacco use at home. This has yet to be enacted. Meanwhile, at the end of March 2020, in response to COVID-19, the government banned the sales of alcohol and all tobacco products. In June, while restrictions on alcohol sales were lifted, the tobacco ban remained in place, but with little effect as a study from the University of Cape Town revealed.238

Product safety: a matter of global concern

A key requirement for SNP consumers, wherever they live in the world, is to be assured of the quality of the products they are using.

We live in a world full of counterfeit goods: fashion and fashion accessories, technology, watches, medicines and so on. SNP are no different in this respect. Almost as soon as it was launched, fake IQOS devices were in circulation.

Given that currently there are around 68 million vapers worldwide, the incidence of devices catching fire or exploding is rare, although will inevitably be reported in the media. This can happen for a number of reasons, primarily consumer error in constructing their own devices, but also poorly made counterfeit devices and poorly made or cheap batteries where the contacts are exposed and come into contact with a metal object like keys in a consumer’s pocket.

SNP consumers need to be assured of the quality of the products they are using.

There are some potential quality issues around large bottles of non-nicotine e-liquids known as short-fills, or shake and vape - so named because they are not filled to the top, allowing users to add their own bottle of nicotine. Shortfills developed as a get around for the EU Tobacco Products Directive (TPD) rules dictating that nicotine containing e-liquids need to be tested and notified and can only be sold in 10ml bottles. As short-fills fall outside the TPD they are much cheaper to bring to market than nicotine containing e-liquids and so are available in many more flavours. UK vaping trade bodies have been calling for all vapable liquids, including short-fills, concentrates and any vapable cannabis product, to be notified to the UK MHRA.

Safety standards

A number of international, regional and national bodies have developed or are developing standards for SNP.

The International Organisation for Standardisation (ISO) is an independent NGO with a membership comprising standards organisations of 162 member countries. It is the world’s largest developer of voluntary international standards and facilitates world trade by providing common standards between nations. Over 20,000 standards have been set, covering everything from manufactured products and technology, to food safety, agriculture and healthcare.

The ISO tobacco committee has established a vaping products sub-committee with two working groups, looking at safety and quality requirements for vaping devices and e-liquids, test methods for devices and e-liquids, determination of substances in e-liquids, testing conditions, equipment, reference products, emissions, vaping machines and user information and services provided by retailing.239 There are now six standards specific to vaping liquids and devices, covering the composition of e-liquids and emissions from those devices – two are published and four are under development.240

At the regional level there is the European Committee for Standardisation or CEN, which has four working groups covering devices, e-liquids and emissions. The CEN technical report Electronic cigarettes and e-liquids – constituents to be measured in the aerosol of vaping products was published in 2018 and provided “a list of constituents of interest”:

- Prefilled products such as disposable devices and refill cartridges.

- E-liquids sold in refill containers.

- The following categories of hardware: coils or other heater elements of the vaping product, atomisers, rebuildable atomisers and all open tank or dripper products with inbuilt atomisers, including clearomisers.

The CEN states:

“These standards will provide a common framework for all electronic cigarettes and e-liquid products sold in all EU markets. This work also aims to increase the safety of all the European users, by setting consistent safety and quality standards of the products and improving consumer information across all EU Member States. These documents, recognized and applicable in all CEN members’ countries, will give advice and help manufacturers, importers, exporters and distributors to adhere to standardised safety and quality requirements”.

To what extent the standard will now apply to the UK remains to be seen.241

In the UK, the British Standards Institute (BSI) produced PAS 54115 in 2015, a manufacture, importation, testing and labelling guide covering vaping products, including devices, e-liquids and e-shisha. Subjects covered include: the purity of e-liquid ingredients; potential contaminants from device materials and potential emissions from devices; an outline for the toxicological and chemical analysis of emissions; and, the safety of batteries and chargers. The BSI have now published PAS 8850:2020, Non-combusted tobacco products – Heated tobacco products and electrical tobacco heating devices – Specification.242

The French Association Française de Normalisation (AFNOR) has published similar guidance standards.

There is a voluntary product standard for Swedish snus called the Gothiatek standard, introduced by the snus industry in 2001.243 In 2007, the Gothiatek standard was accepted as a standard for all smokeless tobacco products (STP) by the European Smokeless Tobacco Council (ESTOC), an organisation representing all the major manufacturers of snus.

The Gothiatek standard sets maximum permissible levels for several unwanted substances. The mandated maximum levels have been lowered on several occasions since the introduction of the standard. In 2010, the WHO Study Group on Tobacco Product Regulation proposed maximum levels for some nitrosamines (NNN, NNK) and one PAH (BaP, benzo(a)pyrene) in STPs. These levels are, however, higher than the maximum levels currently mandated by Gothiatek as well as below the maximum levels for snus set by the Swedish Food Authority which came into force on 11th April 2016.244

The direction of travel in many countries is to enact more stringent controls on SNP, either aligning regulations with controls on tobacco, enacting flavour bans or worse.

This type of policy is driven by a view of SNP as a threat to public health rather than an opportunity to complement existing efforts at reducing the effects of the smoking epidemic. Another underlying driver of the anti-THR narrative may be that the whole enterprise has been driven from the bottom up by consumers and brought to a wider market by commercial interests, taking it out of the hands of public health agencies entirely.

But whatever the context or motive, anti-THR policies are in breach of a clutch of international treaties which declare the universal right to health with nobody left behind.

The worst impacts of SNP prohibition will be experienced by smokers and those already-marginalised groups who smoke the most and consequently suffer most from smoking-related disease and death: indigenous communities, LGBTQ+ communities, those in prison, the homeless, those in extreme poverty and those suffering mental health, drug and alcohol problems.

Whatever the context or motive, anti-THR policies are in breach of a clutch of international treaties which declare the universal right to health with nobody left behind.

- Union Position Paper on E-cigarettes and HTP sales in LMICs. (n.d.). The Union. Retrieved 20 July 2020, from https:// www.theunion.org/what-we-do/publications/technical/union-position-paper-e-cigarette-and-htp-2020

- CTFK webinar on control of SNP https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9RczYcBZkyY&feature=youtu.be&t=319

- Jacob, G. (2004). Without Reservation. Chicago Journal of International Law, 5(1). https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/ cjil/vol5/iss1/19, p.287-302

- Expose Tobacco Industry Manipulation, Save the Next Generation. (2020). https://www.ggtc.world/exposetobacco/

- Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems and Electronic Non-Nicotine Delivery Systems (ENDS/ENNDS). (2016). [Statement]. WHO. https://www.who.int/fctc/cop/cop7/FCTC_COP_7_11_EN.pdf

- WHO Study Group on Tobacco Product Regulation. Report on the scientific basis of tobacco product regulation: seventh report of a WHO study group. (No. 1015; WHO Technical Report Series). (2019). World Health Organization. https://apps. who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/329445/9789241210249-eng.pdf

- WHO | The Convention Secretariat calls Parties to remain vigilant towards novel and emerging nicotine and tobacco products. (n.d.). WHO; World Health Organization. Retrieved 1 July 2020, from http://www.who.int/fctc/mediacentre/ news/2019/remain-vigilant-towards-novel-new-nicotine-tobacco-products/en/

- WHO FCTC. (2020, June 15). https://www.facebook.com/FCTCofficial/posts/2578089132443187

- Just to reiterate, while the WHO plays host to the FCTC Secretariat and is the legal employer of staff, the Secretariat is technically independent of both the WHO and its tobacco control programme and answerable instead to the signatory countries to the FCTC.

- European Food Safety Authority. (2018). Approaches to assess and manage scientific uncertainty: examples from EU ANSA agencies. (Publications Office of the European Union, pp. 33–34) [Research policy and organisation]. Publications Office of the European Union. http://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/9880c8bc-83eb-11e8-ac6a- 01aa75ed71a1

- Information webinar on tobacco policy. Videoconference. Draft summary record. (2020, March 19). https://ec.europa.eu/ health/sites/health/files/tobacco/docs/ev_20200319_sr_en.pdf

- STATE System E-Cigarette Fact Sheet. (2020, March 18). https://www.cdc.gov/statesystem/factsheets/ecigarette/ ECigarette.html

- Office of the Commissioner. (2020, March 24). FDA grants first-ever modified risk orders to eight smokeless tobacco products. FDA. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-grants-first-ever-modified-risk-orders-eightsmokeless- tobacco-products

- Associated Press. (2020, February 28). House passes bill to ban the sale of flavored e-cigarettes and tobacco products. NBC News. https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/politics-news/house-passes-bill-ban-sale-flavored-e-cigarettes-n1145186

- Callard, C. (2020, May 9). Physicians for a Smoke-Free Canada: Nova Scotia and Ontario move to curb high-nicotine vaping products. Physicians for a Smoke-Free Canada. http://smoke-free-canada.blogspot.com/2020/05/nova-scotiaand- ontario-move-to-curb.html

- Smoking in Mexico. Death, illness and tax situation. (2017). IECS. https://www.iecs.org.ar/wp-content/uploads/Flyer_ tabaquismo_MEXICO.pdf

- Mexico top court rules e-cigarette sales should be allowed. (2019, November 14). AP NEWS. https://apnews.com/066c90 42871c4e60afea6dedf87c5b48

- Sharan, R. N. et al. (2020). Patterns of tobacco and e-cigarette use status in India: a cross-sectional survey of 3000 vapers in eight Indian cities. Harm Reduction Journal, 17(1), 21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-020-00362-7

- Agence France-Presse. (2019, September 18). India bans e-cigarettes as global vaping backlash grows. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2019/sep/18/india-bans-e-cigarettes-as-global-vaping-backlash-grows

- Withnall, A. (2019, September 18). India bans vaping after government passes emergency order. The Independent. https:// www.independent.co.uk/news/world/asia/india-bans-vaping-law-e-cigarettes-modi-disease-deaths-a9110201.html

- Cha, S. (2019, October 25). South Korea warns of ‘serious risk’ from vaping, considers sales ban. Reuters. https://www. reuters.com/article/us-health-vaping-southkorea-idUSKBN1X205E

- References and documents for this section provided by local key informants.

- The Globally Harmonized System of Classification and Labelling of Chemicals or GHS is managed by the UN concerning the labelling schemes for hazardous materials as well as their classification.

- Corrales, N. (2019, November 20). Duterte warns judiciary not to mess with vaping, e-cigarettes ban. INQUIRER.Net. https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/1192504/duterte-warns-judiciary-not-to-stop-his-ban-on-vaping

- Vaping and smokeless tobacco. Position Statement on vaping. (2017). Ministry of Health NZ. https://www.health.govt.nz/ our-work/preventative-health-wellness/tobacco-control/vaping-and-smokeless-tobacco

- Although at the time of writing, the government is actively considering a ban on oral SNP such as snus.

- Olatunji, U. (2020, March 30). Nigeria Is Crying Out for Vapes That Smokers Can Afford. Filter. https://filtermag.org/ nigeria-vapes-afford/

- E-Cigarettes: Use and Taxation (English) (WBG Global Tobacco Control Program.). (2019). World Bank Group. http:// documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/356561555100066200/E-Cigarettes-Use-and-Taxation

- Daniel, L. (2018, August 15). New smoking laws set to extinguish vaping in South Africa. The South African. https://www. thesouthafrican.com/news/new-smoking-laws-vaping-in-south-africa/

- Norcia, A. (2020, May 28). How South Africa’s Coronavirus Tobacco Prohibition Backfired. Filter. https://filtermag.org/ south-africa-coronavirus-cigarettes-ban/

- Tranchard, S. (2016, April 21). Vape and vapour products make their debut in international standardization. ISO. https://www.iso.org/cms/render/live/en/sites/isoorg/contents/news/2016/04/Ref2074.html

- ISO – ISO/TC 126/SC 3 – Vape and vapour products. (n.d.). Retrieved 1 July 2020, from https://www.iso.org/ committee/5980731/x/catalogue/

- CEN/TR 17236:2018. (2018, September 26). European Committee for Standardization. https://standards.cen.eu/dyn/www/ f?p=204:110:0::::FSP_LANG_ID,FSP_PROJECT:25,65461&cs=1369EF3BCBACA65582FFB337FE84BA1B3

- PAS 8850:2020 heated tobacco products specification. (2020, July). British Standards Institution. https://shop.bsigroup. com/ProductDetail?pid=000000000030396623

- Rutqvist, L. E. et al. (2011). Swedish snus and the GothiaTek® standard. Harm Reduction Journal, 8, 11. https://doi. org/10.1186/1477-7517-8-11

- Swedish Match – Snus and the Swedish Food Act. (2016). https://www.swedishmatch.com/Snus-and-health/snus-and-theswedish- food-act/