Project fear: the war against nicotine

Following the publication of reports by the Royal College of Physicians and the US Surgeon General in the early 1960s, the battle lines were drawn between the tobacco industry on the one hand and anti-smoking organisations and medical and public health authorities on the other.

For its part, the industry did everything it could to deflect attention away from the lethality of its product; sowing confusion by publishing conflicting evidence; intense lobbying to stymie attempts at regulation; trying to convince smokers that filter cigarettes were safer and so on – while aligning an aspirational lifestyle with smoking, as much as with the product itself.

On the other side, US anti-smoking campaigners were doing their utmost to challenge the tobacco companies. Using the growing body of evidence on the baleful effects of smoking, American anti-smoking campaigners scored victories in pushing for legislative change and teamed up with state governments in winning lawsuits against the industry. Ultimately, companies concluded the Master Settlement Agreement (MSA) in November 1998, paying billions of dollars to the states to cover smoking-related health costs (although over the years, much of that money simply went to filling holes in state budgets).171 And those battles have continued around the world, with plain packaging legislation, bans on advertising and public smoking and ever-higher rates of taxation. But there is a sting in the tail.

The new nicotine products have been disruptive to the tobacco industry which has had to adapt or get left behind in a burgeoning market. The development of SNP has also been hugely disruptive to the deeply embedded narrative of anti-smoking campaigners. The growing use of SNP and the re-evaluation of the relative benefits of smokeless tobacco has split the global public health community. It has generated a new era of uncertainty and confusion around nicotine consumption. The longstanding ‘heroes and villains’ narrative has been disrupted to the extent that – regarding THR – some major ‘heroes’ of the tobacco wars are now public health ‘villains’ who are putting smokers’ lives at risk.

What started out in the 1960s as a war against smoking, over time became an issue of international tobacco control. Thanks to the new generation of smoke-free products, the over-arching strategy now reveals itself as a ‘war against nicotine’: in effect, a war against consumers.

From the 1970s onwards, the message about the dangers of smoking began to permeate populations in high income countries, coupled with increasing enthusiasm for a healthier lifestyle. Smoking levels were falling in these countries as the campaign against smoking gained the upper hand.

New safer nicotine products have been disruptive both to the tobacco industry and to tobacco control.

It should be the mission of every health-related NGO to close should its disease of focus be eradicated. Instead, rather than disappear, they often re-invent themselves.172 Within the anti-smoking realm, US NGOs such as the CTFK had been dealing with a diminishing cause, as smoking among teenagers was also falling in line with adult rates. However, the arrival of vaping devices on the US and European markets in 2006/07 was manna from heaven for those who wanted to continue to fight the good fight – even at the expense of those likely to benefit from nicotine innovations.

The narrative which followed this seismic shift in the tobacco landscape was and remains messy and controversial. It’s driven by a mix of reactivity, polarised positiondriven analysis and campaigning interests, emotive media reporting, hidden conflicts of interest and adversarial relationships between scientists, experts and policymakers, along with an increasingly contested evidence base.

Two overlapping sociological concepts help understand what is going on. One is the role of moral entrepreneurs who seek to impose their own standpoints on society at large.173 The second are availability heuristics, or put more simply, confirmation bias – whereby the public and the media fail to check information, and simply accept cascaded wisdom from ostensibly trusted sources based on gut reactions or plausibility. In other words, relying on information we instinctively think we know to be true.174

Moral entrepreneurs can be individuals, religious groups or formal organisations who press for the creation or enforcement of a ‘norm’ for any number of reasons, altruistic or selfish. They generate moral panic by expressing the conviction that a threatening social evil exists that must be combated and are not unduly concerned with the means of achieving their desired outcome.

Moral entrepreneurs seek to impose their own standpoints on society at large. They generate moral panic by expressing the conviction that a threatening social evil exists.

Harry Anslinger and the marijuana moral panic

Harry Anslinger (centre), flanked by Col. C.H.L. Sharman, Chief of Canadian Narcotic Control (left) and Assistant Secretary of Treasury Stephen B. Gibbon (right), in 1937.

Care needs to be taken in attributing significant developments in public discourse to one individual. But it would not be stretching a point to identify Harry Anslinger as the architect of America’s moral panic around marijuana in the 1930s. A classic example of the moral entrepreneur, he was given the job of creating the Federal Bureau of Narcotics after a failed career trying to enforce alcohol prohibition.

The new agency was short of funds, while the newspapers were full of the wellrehearsed threat of drugs like cocaine and heroin. Anslinger realised the best way to attract Congressional money was to manufacture a new drug scare. The easy targets for this were already despised immigrants from Mexico and those on the edges of society like musicians, small time crooks and sex workers, who together comprised a majority of marijuana consumers. Anslinger combed the crime records to find examples of murders committed by immigrants supposedly under the influence of marijuana. With the willing assistance of faith and moral reforming groups, doctors and a salacious press, he promulgated the idea that marijuana drove people homicidally mad.

The narrative was extended to the now familiar ‘threat to young people’ in a cascade of articles and lectures, culminating in his film Reefer Madness. By the 1950s, however, the trope was wearing a bit thin, even with politicians. To secure more funding, he changed tack and suggested that while marijuana itself did not necessarily drive people to madness, it did lead them inexorably through the gate to the world of ‘hard’ drugs.

Anslinger succeeded due to a climate of general ignorance about the drug. The wider public had little personal experience of marijuana. The information was coming directly from his office, delivered by credible sources such as Anslinger himself and doctors in white coats, to a public and a press prepared to believe the worst about Mexican immigrants.

Harry Anslinger, as head of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics, scared the American public by suggesting that marijuana was a gateway to hard drugs.

Stanton Glantz

In the same vein, long-time anti-tobacco activist Stanton Glantz from the University of California turned his attention to SNP shortly after tobacco companies expressed an interest in the market. He has been able to create an Anslinger-like cascade of misinformation through the publication of numerous papers and many conference and media appearances. These have also served to keep government grants flowing to his employer, amounting to millions of dollars over many years. Like Anslinger, he is an archetypal moral entrepreneur and is seen by many as the go-to expert on a subject around which swirls much ignorance.

During his time fighting the war against smoking, Glantz made this assertion about his research priorities during the Q&A session of a tobacco conference in 1992. “If it comes out the way I think, will it make a difference? And if the answer is ‘yes’ then we do it, and if the answer is ‘I don’t know’ then we don’t bother. Okay? And that’s the criteria.”175

It is hard to come to any other conclusion than Glantz looks for ways to deliver the bad news before he starts, similarly known in scientific circles as confirmation bias. This has carried over into anti-vaping research.

His research in this area is often subject to severe criticism by peer researchers. Two examples will suffice.

In 2015, Glantz published a meta-analysis to claim that smokers who vaped reduced their chance of quitting by 28 per cent. However, he selected only those studies of current smokers who had previously vaped and, obviously for that group, vaping didn’t work.176

Unexpected criticism of the paper came from the American Legacy Foundation or Legacy, a leading tobacco control research and policy NGO established in 1998. It was a beneficiary of the MSA, receiving what amounted to a start-up grant of $1.55bn. In 2001, the Foundation granted $15m to the University of California in San Francisco to establish a library of tobacco industry documents and created an endowed chair held by Stanton Glantz. Surprising then, that the agency would openly criticise a Glantz paper. Except the scientists who worked for Legacy – before it was renamed the Truth Initiative (TI) – adhered to good scientific standards and backed tobacco harm reduction. [see box on next page].

Legacy staff wrote a detailed literature review on THR products which was sent to the FDA ahead of three FDA evidence review workshops. At the time, the Glantz study was only available on the university website, to which the Legacy review referred in its notes. Legacy observed:

“While the majority of the studies we reviewed are marred by poor measurement of exposures and unmeasured confounders, many of them have been included in a meta-analysis that claims to show that smokers who use e-cigarettes are less likely to quit smoking compared to those who do not. This meta-analysis simply lumps together the errors of inference from these correlations. As described in detail above, quantitatively synthesizing heterogeneous studies is scientifically inappropriate and the findings of such meta-analyses are therefore invalid.”177

With his junior colleague Sara Kalkhoran, Glantz went on to publish the study in Lancet Respiratory Medicine in 2016,178 only to be sharply criticised by tobacco experts writing for independent science communication charity, the Science Media Centre. Professor Ann McNeill from the National Addiction Centre in London said:

“This review is not scientific. The information included about two studies that I co-authored is either inaccurate or misleading. In addition, the authors have not included all previous studies they could have done in their meta-analysis. I believe the findings should therefore be dismissed. I am concerned at the huge damage this publication may have caused – many more smokers may continue smoking and die if they take from this piece of work that all evidence suggests e-cigarettes do not help you quit smoking; that is not the case.”179

A second paper met with an even harsher reaction – a retraction from the publishing journal. In June 2019, Glantz and Dharma Bhatta published a paper in the journal of the American Heart Association. It claimed that smoking and vaping posed an equal risk of heart attack, with dual use putting vapers at even more risk. The claim received widespread media coverage.

In response, Professor Brad Rodu from the University of Louisville, Kentucky, performed his own analysis on the same data used by Glantz. Rodu ascertained that those who had suffered heart attacks had done so before they started vaping.

Rodu wrote to the journal demanding a retraction. This was followed up by a supporting letter backing retraction, signed by several public health scholars. Journals are loathe to retract papers as it exposes weaknesses of their peer review process. Eventually, the paper was retracted – under an excuse that Glantz did not have access to all the data, prompting him to claim the journal has been got at by ‘e-cig interests’.180

These examples raise serious questions about the validity of research when conducted by those also engaged in campaigning activities linked to their research. Former UK ASH Director and equally fervent anti-THR advocate Mike Daube tellingly agrees that research is compromised by campaigning. Referring to pioneering British tobacco researchers Richard Doll and Bradford Hill’s refusal to engage in anti-smoking activities, he said “the researcher is seen to lose his objectivity as soon as he becomes a campaigner”.181

Legacy and The Truth Initiative (TI)

In addition to funding an endowed chair and the tobacco industry documents library at the University of California San Francisco, The American Legacy Foundation established the Steven A. Schroeder Institute for Tobacco Research and Policy Studies (SITRPS) as a national resource to conduct science to inform tobacco and nicotine policy. From 2008 until about 2016, the SITRPS conducted research, systematic reviews and commentaries, while also communicating its work more widely with public-facing fact sheets. The research reflected the SITRPS scientists’ initial scepticism about harm reduction, but their support grew in accordance with the evidence. They were backed by The Legacy leadership of then-president and CEO Dr Cheryl Healton and Chief Operating Officer David Dobbins. Both Healton and Dobbins signed the letter attached to the 2015 literature review, which was sent to the FDA, as well as several other documents and testimony presented at FDA hearings on what the best science reflected at the time.

When Cheryl Healton left and Legacy entered a year of transition, the Legacy board of directors’ chair, Iowa State Attorney-General Tom Miller, continued to back the science-based approach to tobacco harm reduction. Everything appeared to change between 2015–2018. Former ad agency executive Robin Koval was appointed as President and CEO, while Tom Miller left the now renamed TI board in 2018 having completed his nine-year stint. The organisation’s work became focused on youth prevention and took on an entirely prohibitionist approach.

Subsequently, almost all the Schroeder Institute’s leadership and core research faculty left for other positions in 2016-2018. Within a year of the leadership changes, material in support of harm reduction was removed from the TI website. The organisation now aligned itself with the anti-harm reduction ideology of the CTFK. SITRPS was incorporated into existing TI program evaluation infrastructure and is similarly aligned with the TI’s advocacy and ideological goals.

Risk perception

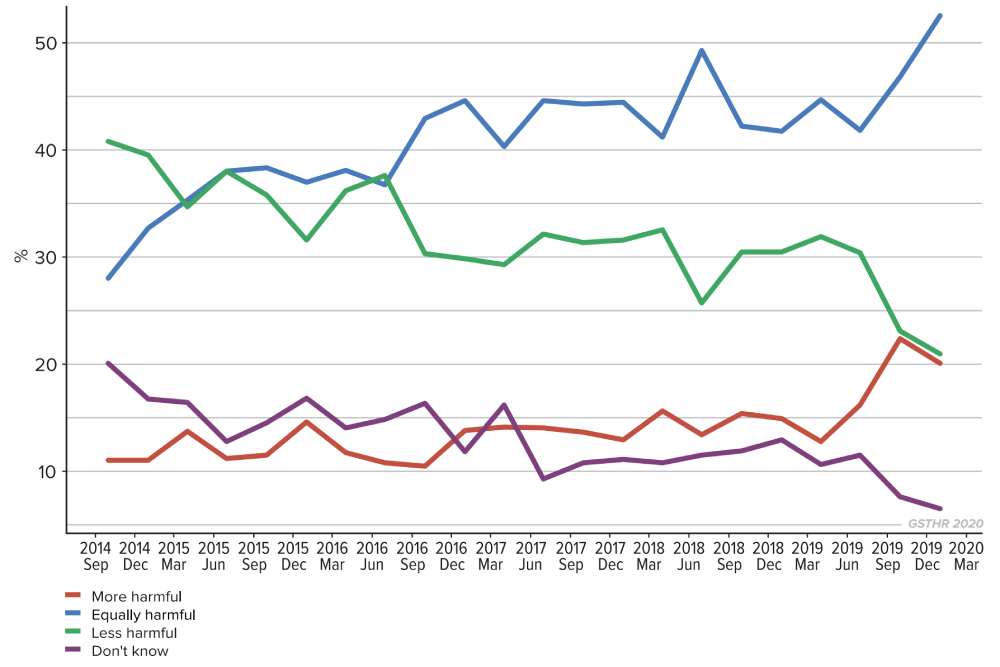

Just how much damage is being done can be seen by the worsening perception of the relative safety of SNP among existing smokers.

Even in the UK, where the government and public health authorities have taken a world-leading pragmatic approach to THR and publicised support for switching, the proportion of smokers believing that smoking and vaping are equally harmful has increased from 28 per cent in the last quarter of 2014 to over 52 per cent in the first quarter of 2020. In the first quarter of 2020, a further 21 per cent said that vaping was more harmful than smoking .182 This means most smokers believe that vaping is as harmful or more harmful than smoking. To quote the latest Public Health England report on vaping in England: “It is of concern that negative beliefs about the harms from vaping might prevent smokers from switching to vaping and they would therefore continue to be exposed to the extremely high levels of harm caused by smoking.”183

Harm perceptions of e-cigarettes compared with cigarettes

N=19239 current smokers who do not currently use e-cigarettes

http://www.smokinginengland.info/sts-documents/

73

per cent

the proportion of smokers in the UK who now believe that vaping

is as harmful or more harmful than smoking.

In the US, a survey concluded that smokers’ perceptions of the relative safety of SNP over cigarettes worsened between 2008–2017. That was before the public scare about cases of VITERLI illnesses and deaths.184 The picture is the same in Canada. The Angus Reid Institute conducted a general population survey about vaping and found that the number of vapers in Canada is on the rise; from just 9 per cent of smokers having tried vaping in 2013 to 25 per cent in 2019. 74 per cent of those questioned said either that they had vaped or that they knew friends or family who had. Yet those who thought vaping did more harm than good increased significantly in just 12 months – from 35 per cent in 2018 to 62 per cent in 2019.185

Follow the money

While it might appear that organisations across the world are operating independently in their opposition to THR, the reality is that they are bound together by one critical element – money.

While it might appear that organisations across the world are operating independently in their opposition to THR, the reality is that they are bound together by one critical element – money.

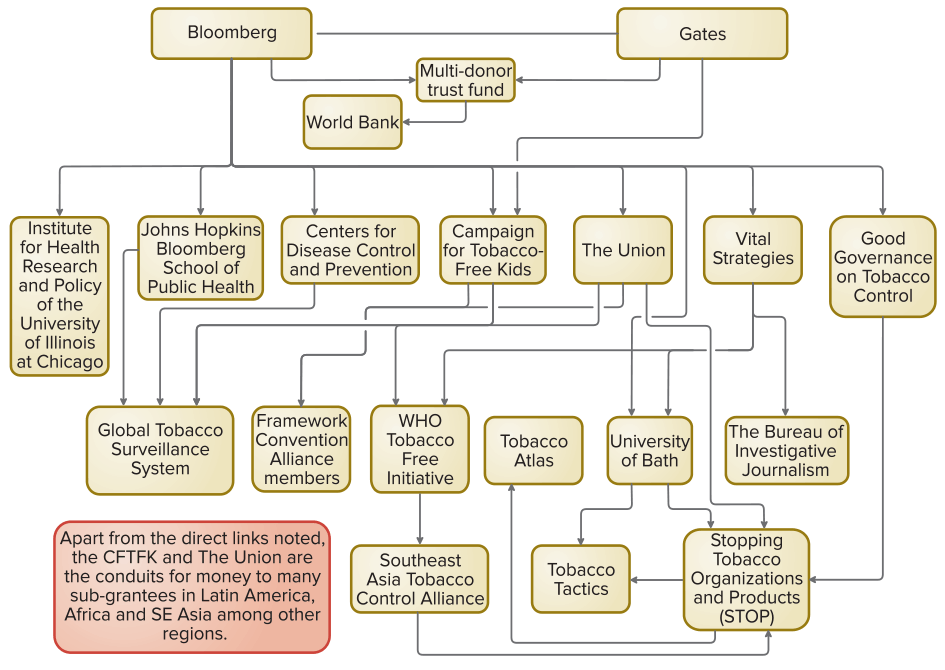

The US is the epicentre for all anti-THR funding across the world, and what follows focuses on US funding structures. There are two primary sources of income for those who are actively campaigning against THR. The first is US federal and state funding for domestic campaigns. The second is donor funds, provided mainly by Bloomberg Philanthropies (BP) with support from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (BMGF), for domestic US and global campaigning and policy work. Funding has also been provided for anti-THR campaigning by a pharmaceutical industry anxious to protect its smoking cessation product interests.

The USA is the epicentre for all anti-THR funding across the world.

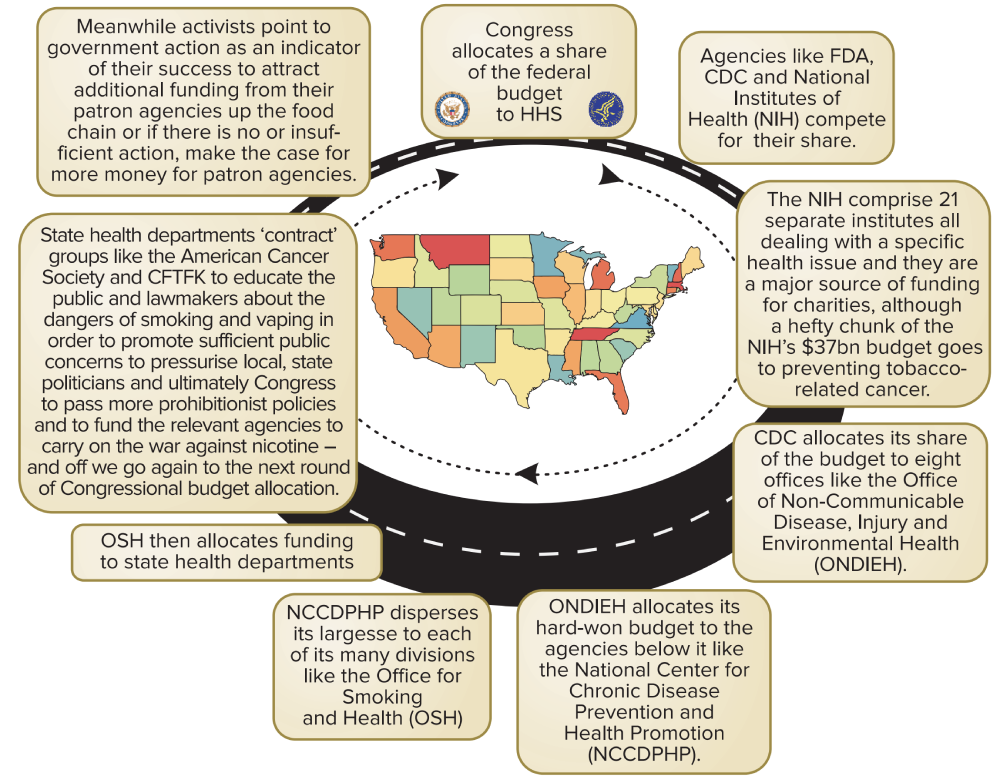

US Government186

Money flows downwards from the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), who in turn have to compete with all the other departments in convincing Congress of the value of their services in the fight for a share of the Federal budget. However, once a budget is secured, agencies within the HHS like the FDA, CDC and National Institutes of Health (NIH) are in competition for a slice of the pie. They all understand there is nothing more effective at loosening the public purse strings than declaring an epidemic that must be tackled.

But these agencies need to prove their case – and this is where a co-dependency cascade begins. The hottest health topic before COVID-19 was the outbreak of vapingrelated deaths, which helped solidify the dangers of the alleged epidemic of youth vaping. This was the subject most likely to attract HHS budget holders.

The US government funding roundabout looks like this:

Agencies like the FDA and CDC often consult with and take briefings from a number of long-established, well-funded and influential health advocacy groups. To the public, these groups appear to be generating advice that is based on medical and scientific expertise, in the service of public well-being and absent of any bias. However, groups like CTFK, backed by advocacy-driven research, are in fact acting as moral entrepreneurs. They are generating the marketing and press releases which stimulate public concern.

While the media provide the public megaphone, NGOs engage in the kind of political activism forbidden to government agencies, putting pressure on politicians and legislators to act in the face of public clamour. In fact, politicians and government officials need external allies to give the impression they have responded positively to community concerns; proof they are listening to the people. As Franklin Roosevelt famously said, “OK. You’ve convinced me. Now go out there and bring pressure on me.”

Philanthrocapitalism

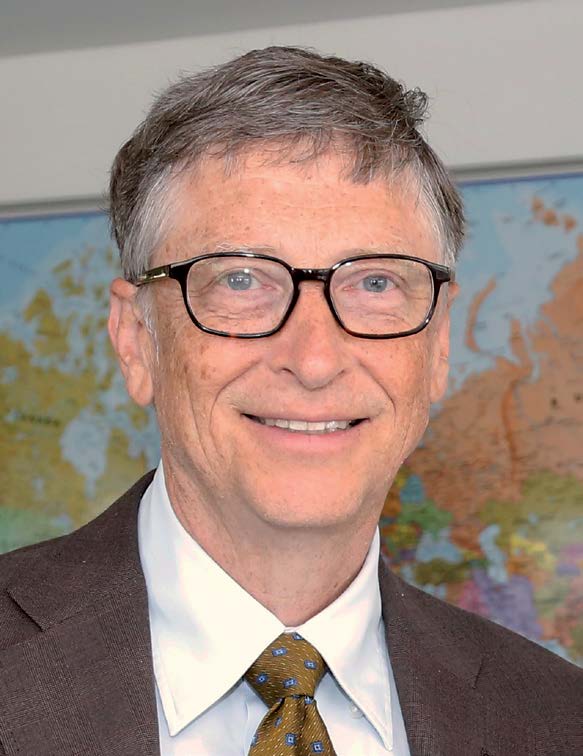

The second and more significant financial input into both US and global campaigning against THR has come from Bloomberg Philanthropies (BP), with some assistance from The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (BMGF).

Foundation funding is differentiated from other forms of charitable financing as there are no public donations, government or other charitable third-party funding. Money derives from the profits of the founder’s business and investment interests. Foundations are nothing new; the Rockefeller Foundation was established in 1913; the Ford Foundation in 1936. A new ethos driving modern day philanthropy applies management methods and metrics to the running of philanthropic projects on the basis that doing good is good for business.

The term philanthrocapitalism was coined in 2006 in The Economist by two economists Matthew Bishop, New York bureau chief for The Economist, and Michael Green, previously employed in the UK Department for International Development, who celebrated this new approach in their 2008 book Philanthrocapitalism: how the rich can save the world.

Bishop and Green argued that the hallmarks of globalisation, such as the removal of trade barriers and cheap air travel, put countries at greater public health risk of both communicable (infections) and non-communicable diseases caused by drinking, smoking and unhealthy diets. However, many countries, especially LMIC, were illequipped to deal with all forms of disease, especially in the wake of the financial crash of 2007-08. Moreover, the crash also impacted on higher income countries, limiting their ability and willingness to contribute to organisations like the WHO. So, the superwealthy weighed in to ‘do their bit’.

The most significant financial input into US and global campaigning against THR has come from Bloomberg Philanthropies with some assistance from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

Bill Gates, The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

And quite a bit it turned out to be. The BMGF was established in 2000, from the personal Microsoft fortune of Bill Gates. In 2006, BMGF was gifted $37bn by Warren Buffet from his own investment fund and now has assets worth close to $50bn distributed primarily in support of overseas infectious disease control and agriculture, and US education. Michael Bloomberg had been donating to US-based causes since the mid-1980s, backed by personal wealth, also in the region of $50bn. International tobacco control was his first major foray overseas.

Michael Bloomberg, Bloomberg Philanthropies.

As Bill Gates explained in Time magazine in July 2008, the name of the game was not simply altruism, but a large element of ‘what’s in it for me?’ as an investor in philanthropic work. What he called ‘creative capitalism’ meant doing good in poorer countries – by increasing their health and wealth, in the expectation that they would then become consumers. And he was not shy about this, quoting one study that found “the poorest two-thirds of the world’s population has $5 trillion in purchasing power.”187

The BMGF Discovery Center, Seattle, US.

Then there is the issue of funding programmes aimed at non-communicable diseases, where public health officials attempt to influence population lifestyles. This can easily tip over into a development agenda driven as much by the moral outlook of funders, policy makers and programme managers as activities geared to maximise public health. Given that those in the middle and upper levels of the funding hierarchy are mainly from the ‘Global North’, arguably there is a neo-colonial angle to international tobacco control, whose programmes would hardly exist without Bloomberg’s millions.

Over the past 15 years, a tangled web of well-funded, well-organised, inter-dependent grantees, sub-grantees, associates and partners has spun out across the world. The programmes being funded have increasingly morphed into industry-obsessed, antinicotine programmes directed as much, if not more, against tobacco harm reduction as reducing harm from smoking.

International tobacco control programmes would hardly exist without Bloomberg’s millions.

How has this come about?

Michael Bloomberg became Mayor of New York on 1st January 2002. Health services in the city are run under the auspices of the NY City Health Department (NYCHD), headed up by the Health Commissioner, a political appointment. The incoming Mayor appoints the Health Commissioner. The Commission put together a shortlist of potential candidates. On that list was a ‘wild card’: Tom Frieden.

Frieden’s mentor at Edinburgh University, where he had conducted his post-doctoral research, was Sir John Crofton, a pioneer in the treatment of TB and, from the 1950s onwards, an ardent anti-tobacco campaigner. His wife Eileen Crofton founded ASH in Scotland, becoming its first director. Another disciple of Crofton was Judith Mackay, a well-known figure on the international tobacco control scene, working mainly in LMIC.

Frieden had been a public health doctor in NYCHD, heading up the Bureau of TB Control. He was a champion of ‘directly observed therapy short courses’ (DOTS) for TB, which worked on the principle that more people would be cured of TB if their full course of treatments was directly observed by a health worker, rather than allowing the patient to self-administer and run the risk of non-compliance. Using this strategy, Frieden was credited with turning around New York City’s TB outbreak of the early 1990s.

While NYCHD were considering candidates for Commissioner, Frieden was seconded to India to run another DOTS programme. Accompanying Frieden to manage the US International Development money for the programme was Jose Luis Castro, a finance officer also from NYCHD.

To be considered for the post of Health Commissioner was a significant jump in seniority for Frieden. He went back to New York, was interviewed by Bloomberg, and reputedly said he would take the job if Bloomberg did something about smoking in New York City. Frieden was kicking at an open door: Bloomberg had been a 60-a-day smoker but was now on the road to Damascus. By 2003, driven by Frieden, Bloomberg had raised cigarette taxes in NYC, established a quit line and social services for smokers and launched massive anti-smoking campaigns overseen by Sandra Mullins, Director of NYC health communications. Most significantly, Bloomberg and Frieden successfully implemented a smoking ban in bars and restaurants, which resulted in a significant adult smoking decline in NYC and became a model for other cities.

Presumably because of his overseas experience with DOTS and keen to replicate the tobacco control successes in New York, Frieden convinced Bloomberg to pump $125m over two years into international tobacco control efforts in the worst affected poorer countries. There was no Gates-style Foundation, so the money was to be dispersed through the Bloomberg Partners (see below).

Meanwhile, other limited foundation funding was in play. From 2000–2006, George Soros’ Open Society Institute (OSI) had been funding tobacco control programmes in Central and Eastern European and former Soviet Republics. With its track record of funding drug and harm reduction programmes, OSI could not understand the attitude of some mainstream tobacco control activists who even then had no time for the limited tobacco harm reduction options available.

In 2005, OSI convened a meeting in New York which brought together harm reduction experts, including smokeless tobacco researcher Professor Brad Rodu, with tobacco control experts. The dialogue was robust but inconclusive and, a year later, OSI ended its funding for tobacco control.

Before OSI stopped funding tobacco control, it drew attention to how little was spent on the issue: a survey found that outside of national programmes, the total amount of spend on international tobacco control was only $27m a year. In early 2006, OSI convened a meeting bringing together leading funders including major cancer charities, the WHO, the World Bank, the UK Department for International Development and BMGF.

BMGF, which had just received its $37bn Buffet windfall, started to develop a $300m+ programme which would start small in a few countries and build up the proof of concept to roll out more widely. However, before the Gates programme could get off the ground, the Bloomberg Global Initiative to Reduce Tobacco Use was duly announced in August 2006.

Then in July 2008, Bill Gates appeared with Michael Bloomberg at a New York City media event to announce a combined commitment of $500 million in tobacco control grants, focused primarily on building the evidence base, social marketing, and policy interventions in China, Southeast Asia, and Africa. Later still, Gates and Bloomberg each donated $5m to a multi-donor trust fund used by the World Bank to fund tobacco tax experts advising LMIC.188

Over the past 15 years, a tangled web of wellfunded, well-organised, inter-dependent grantees, sub-grantees, associates and partners has spun out across the world.

The Bloomberg programme was initially delivered by the Bloomberg Partners: the CTFK, John Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, the CDC Foundation and the World Lung Foundation (WLF). The WLF was an American-based entity, a partner organisation to the Paris-based International Union Against TB and Lung Disease (The Union) to take in funds from US donors, allowing the donor (including Bloomberg) to earn tax relief. It acted as the conduit for funding other Bloomberg partners, including The Union and the WHO Tobacco Free Initiative (TFI).

Jose Luis Castro moved from NYCHD to become financial director of The Union, then in 2013, became its Executive Director and led the transformation of the WLF into Vital Strategies (VS), of which he is now President and CEO.

VS has funded The Bureau of Investigative Journalism and Bath University’s Tobacco Control Research Group which hosts Tobacco Tactics and is a partner in the STOP Campaign. [see box over page]

President Obama appointed Tom Frieden as Director of the CDC in 2009. Frieden left when Trump took over and established Resolve, an initiative of VS, with $225m from BP, BMGF and the Chan Zuckerberg Foundation, whose remit is reducing cardiovascular disease and preventing epidemics globally. Because of Frieden’s experience in infectious disease epidemics, he is now coordinating Bloomberg’s funding of COVID-19 programmes. Frieden is listed as a VS trustee in the organisation’s Inland Revenue Service submission, alongside his near half a million-dollar Resolve salary.

Dr. Thomas Frieden, speaking in his role as Director of the CDC in 2014.

Since 2006, Bloomberg has donated close to $1 billion to promote anti-tobacco efforts, making BP the developing world’s biggest funder of tobacco-control initiatives. In 2013, it was reported that Bloomberg had donated 556 grants in 61 countries to campaigns against tobacco. In August 2016, the WHO appointed Bloomberg as its Global Ambassador for Noncommunicable Diseases.

Gates and Bloomberg brought in business practices from Microsoft and Bloomberg Media insisting that grantees produce data to demonstrate outcomes and impact.189 Where millions of dollars are at play, forensic accountability sounds eminently sensible.

Yet there are serious concerns that while demanding openness and transparency, Big Philanthropy itself has highly secretive decision-making processes, and rather than focusing on in-country needs, instead tends to focus on the personal interests of the founder (like Bloomberg and smoking). Critics also charge that it is mainly interested in short-term funding to achieve quick policy wins for maximum publicity, over actual implementation and longer-term investment.190

$

1

billion

the amount donated by Bloomberg to antitobacco efforts.

For example, although BP grantees operate in a number of countries, the officials of the WHO TFI are not involved in grant-giving decisions.191 Grantees and sub-grantees are often locked in what one critic describes as ‘group think’, creating a cartel mentality,192 which discourages debate on the way programmes are being managed. Then again, self-censorship for fear of losing funding is a gravitational force that makes coercion unnecessary.

The Bloomberg Initiative’s ‘audit culture’ pushes advocates to strive for outputs that can be measured and documented, such as meetings with legislators, leaflets, workshops and phone calls to journalists. These, however, may not lead directly to enforcement of regulations or a long-term decline in tobacco use. Bloomberg Initiative grants awarded to African advocacy groups between 2007 and 2017 shows that of the 79 grants, 51 made to 17 different countries were intended to support passage of comprehensive legislation and/or taxes.193

Financial dependence puts local advocacy efforts at the mercy of funder changes to programmes. For example, in Ghana, Bloomberg added the issue of road traffic accidents to its tobacco control effort. In Tanzania, funders did not renew a grant after advocates were unable to get legislation passed in 2010. Short-term focus undermines local actors’ ability to build the trust and legitimacy needed for policy implementation, ultimately limiting their effectiveness.194

Local advocates cannot easily turn to grantees above them in the tobacco control hierarchy to help them build capacity, because some of these actors (e.g. The Union and CTFK) also depend on Bloomberg or BMGF, making it hard for them to commit to long-term projects that do not show short-term results.

Worse still, one informant for this report said that where the WHO TFI, The Union and CTFK all have their own separate offices in one country managing different programmes, staff in these offices are known to deliberately hide activities from each other, leaving local grantees dancing from one higher-up grantee to the other in an atmosphere of mutual hostility, as funding and fiefdoms are protected.

Financial dependence puts local advocacy efforts at the mercy of funders’ programmes, which undermines local ability to build trust and legitimacy.

This is a ‘simplified’ picture of the direction of the global funding streams, much of which appears devoted to action against THR. There will be many in-country local grantees and other organisations who also campaign against THR and who cite CFTK, Bloomberg and Gates as ‘partners’, without any clarity as to what this means.

The policies are as tangled as the personnel and the processes, so it is impossible to calculate how much of this substantial funding is now being directed against THR. But at least from the perspective of public campaigning, positioning and in-country political lobbying, it must be considerable. It is equally impossible to know to what degree local grantees in the most affected countries genuinely sign up to the anti-THR war against nicotine agenda. However, as many in tobacco control – at whatever level in the funding firmament – approach these issues from a moral or even quasi-religious mindset, dissenting voices would be few. What is clear is that all the Bloomberg-funded agencies oppose THR when linked to the use of SNP.

Examples of anti-THR funding beneficiaries

The sums of money quoted are not a comprehensive accounting, but simply indicate the scale of the resources used to oppose tobacco harm reduction and SNP.

Campaign for Tobacco Free Kids (CTFK)

The arrival of SNP posed a direct threat to the pharmaceutical industry and its multi-billion-dollar global sales of NRT products. “The drugs industry is objecting to the marketing of e-cigarettes and vape pens as a way to quit cancer-causing cigarettes. Pharmaceutical companies…want e-cigarettes to be regulated as medicinal products…At stake: who will take the larger share of Europe’s market for smoking cessation”.195

An anti-smoking NGO was an ideal vehicle for pharmaceutical companies to push their NRT products under a cloak of charitable works. All had an interest in stamping out SNP, providing an example of what economist Bruce Yadel dubbed an unlikely alliance of ‘Baptists and bootleggers’. In the run-up to Prohibition, both groups wanted alcohol banned; for Baptists it was a question of morality, for the bootleggers, simply money.

In this context and since 1995, CFTK has received over $120m from the main pharmaceutical companies selling NRT products; Johnson & Johnson, Pfizer and GlaxoSmithKline. Between 2011-14, CFTK received over $30m from the Gates Foundation. More recently, CTFK receives major funding from BP, primarily to run overseas grants programmes. While funding in the days before SNP would have been focused on reducing smoking among young people, it is clear that much of the organisations’ current work is directed towards campaigning and lobbying against THR and SNP both in the USA and overseas, including $160m from BP to orchestrate a US ban on nicotine flavours.

Pharmaceutical companies... want e-cigarettes to be regulated as medical products... At stake: who will take the larger share of Europe’s market for smoking cessation.

The Union

Formerly the International Union against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, founded in 1920, the Paris-based Union had a laudable track record in the international effort to combat TB. During the 1990s, its focus expanded to include tobacco control. It joined the army of those agencies campaigning against attempts to undermine tobacco control efforts, especially in LMIC. In step with other Bloomberg grantees, this has morphed into a general war against nicotine, particularly aimed at the advent of SNP. The Union also organises the World Conference on Tobacco or Health, which effectively bans anyone supporting THR not just from presenting, but even attending.

Recently, under the slogan, ‘Bans are Best’, the Union (and the CTFK) has been encouraging countries to introduce outright bans on all SNP on the basis of a hyper-inflated interpretation of the ‘precautionary principle’ (See Chapter 6).

Vital Strategies (VS)

Originally, VS was the World Lung Foundation, established as a US-based entity to allow American donors to claim tax relief. It operates globally in public health arenas such as air pollution, lead poisoning, obesity and cardiovascular health. It supports drugs harm reduction. Less beneficial to global public health is its weaponization of tobacco control to attack THR, through joint sub-funding programmes with The Union.

Tobacco Tactics (TT)

A direct Bloomberg grantee and a sub-grantee of both the Union and VS, who themselves are Bloomberg funded, TT is a database produced under the aegis of the Bath University Tobacco Control Research Group. It purports to be an academic resource and claims to be a ‘new model of academic research dissemination’. It was established to track what in its view are examples of tobacco industry interference in tobacco control policies. It has been criticised for selective reporting and analysis. TT has consistently raised doubts about THR and the manufacturers of SNP. Its modus operandi includes ad hominem attacks against THR advocates.

Stop Tobacco Organisations and Products (STOP)

Also housed at Bath University and similarly funded, STOP uses TT information to be the public-face of FCTC196 Article 5. (see next chapter). STOP is often the vehicle for attacking THR researchers and advocates – usually, as with TT, by innuendo.

WHO Tobacco Free Initiative (TFI)

When the Bloomberg Initiative was launched, it was decided that the money should go to the WHO TFI, rather than being channelled through the FCTC Secretariat. The political context for this is the Americans’ general dislike of international treaties, where they feel self-determination could be compromised by treaty obligations that might not be in US’ best interests. In this case, while the US did not ratify the FCTC as signatories, they can attend the Conference of the Parties (COP) meetings, which they do in great numbers to keep an eye on what’s going on. The FCTC Secretariat is hosted by the WHO in Geneva but is not directly answerable to the WHO, but to the Parties to the treaty. Direct funding to the FCTC Secretariat would mean Bloomberg would have less control over how the money was spent.

According to one informant, by the time the Bloomberg money began to flow, personal animosities between the then-respective organisational heads meant that there was already little love lost between the WHO TFI and the FCTC Secretariat – a situation that worsened over time. The FCTC Secretariat has to rely on voluntary contributions from the FCTC Parties, many of whom pay nothing. The Secretariat has petitioned the Parties to establish an investment fund. But the only countries likely to pay up are those who are already contributing – a tall order anyway, but in the light of COVID-19 and the world facing a global recession (if not depression), such a request is likely to prove a non-starter.

Recently, under the slogan, ‘Bans are Best’, the Union (and the CTFK) has been encouraging countries to introduce outright bans on all SNP on the basis of a hyperinflated interpretation of the ‘precautionary principle’.

While the money made available for international tobacco control appears significant, it is very little when compared to the size of the problem. And for all the anti-tobacco activity undertaken across the world, it is clearly not enough. Therefore, it would have been hoped that all those agencies involved would embrace all the possible options to help reduce the smoking epidemic. Sadly, this is not the case. The key players in the Bloomberg sphere of influence refuse to acknowledge a role for THR in combatting the epidemic they have devoted their lives to defeating.

The key players in the Bloomberg sphere of influence refuse to acknowledge a role for THR in combatting the epidemic they have devoted their lives to defeating.

Dirty tricks

But anti-THR campaigning goes further than simply attacking THR. There is concerted effort to smear the reputations of individuals by allegations of industry influence. Simply citing industry influence – with no attempt to articulate whether that is true or how that influence might work – requires the least effort, while being the most damaging way to undermine research.

Direct attacks on individuals comes right out of the playbook of a pioneer of community activism: Saul Alinsky. Quoting Alinsky’s 1971 book Rules for Radicals, former UK ASH director Mike Daube said, “rule one – personalize the problem – the people running these companies are responsible for these (smoking) deaths”.197

The conflation of THR research with alleged industrial duplicity has given the green light to tobacco control activists to encourage conference organisers to withdraw speaking invitations – or even forbid attendance – to those who have been ‘outed’ in this way.

One of the most notorious recent examples of ad hominem attacks has been the treatment of Dr Marewa Glover from New Zealand. Dr Glover is an internationally-respected social scientist and campaigner for smokers within minority ethnic communities and their right to health through access to SNP. Claims that her work is influenced by the tobacco industry have seen her effectively barred from speaking and event sponsors pull out. She was also the subject of a failed whispering campaign to have her 2019 nomination for New Zealander of the Year withdrawn.

Smearing of this sort tends to be done through word of mouth, phone calls and so on with no evidence trail. However, Ashley Bloomfield, New Zealand’s Director General of Health, wrote to all public and district health bosses, specifically telling them not to have anything to do with Dr Glover because some of her work had been funded by the Foundation for a Smoke-Free World. The letter did not offer any evidence as to how this funding might have influenced Dr Glover’s work.

In a circulated New Zealand public heath newsletter, Dr Prudence Stone, CEO of the Public Health Association, claimed that Dr Glover had made false statements to the New Zealand parliamentary select committee considering amendments to the Smoke-free Environments (prohibiting smoking in motor vehicles carrying children) Amendment Bill. At least in this case, Dr Glover received a public apology, “Dr Stone and the PHA retract these comments and unreservedly apologise to Dr Glover for the comments made”.198

Bad science

Researchers need their papers published, as career progression depends on it. Academic institutions need research published to justify grant payments. Most institutions have press officers who hope to attract media attention, so the temptation is to ramp up findings to make a good story.

The media has an unhealthy appetite for health scares, and pre-COVID-19, nothing whetted this appetite more than the ‘dangers’ of vaping. Often, researchers are quite circumspect in their conclusions and are uncomfortable when their press office overegg the research pudding, resulting in sensationalised media reporting. However, in this case, there are vested interests in getting as much bad news out there as possible. Such interests are aided in this by the bias of some medical journals, while others have simply less-than-robust peer-review processes.

Richard Smith is the former editor of the British Medical Journal and on leaving his post wrote a refreshingly honest book entitled, The Trouble With Medical Journals. Commenting on the quality of much research that manages to get into print, often after multiple rejections, he quoted Drummond Rennie, deputy editor of the Journal of the American Medical Association who observed:

“There seems to be no study too fragmented, no hypothesis too trivial, no literature citation too biased or too egotistical, no design too warped, no methodology too bungled, no presentation of results too inaccurate, no analysis too self-serving, no argument too circular, no conclusions too trifling or too unjustified, and no grammar and syntax too offensive for a paper to end up in print.”199

There are numerous examples in the sphere of SNP research which come under the heading of ‘How on earth did that get published?’. Broadly speaking, studies are deficient for a variety of reasons such as: laboratory studies with little relevance to the real world; lack of appropriate comparators; confusion of association with causation; inadequate conceptualisation and control of confounders; meta-analyses that rely on individually-flawed studies; and over-reaching policy conclusions bearing little relation to the research itself.

Readers are referred to the forensically clinical and scientific demolition of bad science to be found at the websites of Clive Bates, Professor Michael Siegel, Professor Brad Rodu, Dr Carl Philips and Dr Konstantinos Farsalinos, among others.200

There are numerous examples in the sphere of SNP research which come under the heading of ‘How on earth did that get published?’.

There are similarly flawed statements from government health representatives and medical and public health organisations. For example, the European Respiratory Association has a long anti-vaping track record. In 2019, it published a position paper in which it asserted that “based on scientifically-backed arguments (sic)…[a] tobacco harm reduction strategy should not be used as a population-based strategy in tobacco control” because THR is:

“based on incorrect claims that smokers cannot or will not quit smoking; reliant upon undocumented assumptions that alternative nicotine delivery products are highly effective as a smoking cessation aid; built on incorrect assumptions that smokers will replace conventional cigarettes with alternative nicotine delivery products; ignorant to the lack of evidence to show that alternative nicotine delivery products are safe for human health”.201

The statement earned a trenchant rebuttal in a letter from Professor John Britton at Nottingham University and several other signatories including Deborah Arnott, CEO of UK ASH. The letter – an exemplary response to common anti-THR claims – began:

“The respiratory community is united in its desire to reduce and eliminate the harm caused by tobacco smoking, which is at present on course to kill one billion people in the 21st century. The stated policy of the European Respiratory Society is to strive ‘constantly to promote strong and evidence-based policies to reduce the burden of tobacco related diseases’.

“In our view, the recent ERS Tobacco Control Committee statement on tobacco harm reduction though well-intentioned, appears to be based on a number of false premises and draws its conclusions from a partial account of available data. It also presents a false dichotomy between the provision of ‘conventional’ tobacco control and harm reduction approaches. We therefore respond, in turn, to the seven arguments presented against the adoption of harm reduction in the Committee’s statement.”202

The WHO campaign against THR

Most damaging of all from a global public health perspective is the anti-THR attitude taken by the WHO. The WHO has made clear that recreational use of nicotine is unacceptable and through the auspices of the TFI and the FCTC, does all in its power to undermine THR.

In December 2019, giving evidence to the Philippine Senate Hearing on E-Cigarettes, Ranti Fayokun from the WHO HQ Department of Prevention of Non-Communicable Diseases claimed vaping products contain toxic and carcinogenic chemicals and metals, affect the developing brain, have caused EVALI since 2012 and led to cannabis use.

Most damaging of all from a global public health perspective is the anti-THR attitude taken by the WHO.

She would not answer the point that on the WHO’s own International Agency on Research on Cancer (IARC) website, it had stated explicitly that:

“Use of the e-cigarette does not involve burning of tobacco and inhalation of tobacco smoke as occurs in cigarette smoking; therefore the use of e-cigarettes is expected to have a lower risk of disease and death than tobacco smoking. Introducing appropriate regulations will minimize any potential risks from e-cigarette use.”203

“E-cigarettes have the potential to reduce the enormous burden of disease and death caused by tobacco smoking if most smokers switch to e-cigarettes and public health concerns are properly addressed”.

The World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland.

In January 2020, the WHO published a question and answer page on ENDS (Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems). In response to severe criticisms, they published an unannounced update that removed some of the most obviously misleading statements, while making no acknowledgement of the corrections. To quote Clive Bates:

“There are nine questions and every single answer provides false, misleading or simplistic information, and this remains true of the 29 January update. It is a disgraceful travesty of science communication and policymaking advice and again puts in question the competence of the WHO – if there is still any doubt about this. But it is so bad that it even fails as anti-vaping activist propaganda – and that is a low bar”.204

The uncompromisingly hostile approach to THR has to be set against a backdrop of tobacco control delivery which as one Lancet editorial observed has been ‘staggeringly slow’.205 Actors in the Bloomberg hierarchy are quick to blame the tobacco industry for slow progress. No doubt industry engagements with governments over the years have played their part. But there are many other factors to consider. These include: the poor uptake of tobacco control measures; that many countries with the worst smoking problems host a commercially important domestic tobacco industry, creating tensions between government departments dealing with business and (often politically weaker) health; and the fact that in countries with limited resources, immediate health issues might take priority over smoking, the deleterious effects of which take years to materialise.

The uncompromisingly hostile approach to THR has to be set against a backdrop of tobacco control delivery which as one Lancet editorial observed has been ‘staggeringly slow’.

One study came to the startling conclusion that there was “no evidence to indicate that global progress in reducing cigarette consumption has been accelerated by the FCTC treaty mechanism.”206

A Bloomberg presentation to grantees claimed that over five years, 14 million lives had been saved.207 Yet, the only tools available to assess, for example, lives saved for non-smokers by introducing smoke-free environments are – at best – modelling and computer simulation techniques. As David Reubi notes, ‘lives saved’ data is beset with problems of overestimation, because of extrapolations, assumptions and generalisations.208

Having laws in place is deemed by the WHO, to be at the ‘highest levels of achievement’ – and many countries can only claim very modest progress. And without the means or the mechanisms for enforcement, these achievements are little more than window dressing.

One study concluded that there was “no evidence to indicate that global progress in reducing cigarette consumption has been accelerated by the FCTC treaty mechanism.”

Given the amounts of money being spent to enact the WHO MPOWER initiative globally, its limitations in actually reducing smoking and increasing lives saved are concerning. The steepest falls in smoking have been in high-income countries. These are states with relatively well-resourced health and social care systems, with substantial sectors of the population attuned to the benefits of a healthier lifestyle.

As the WHO admit, the weakest area of MPOWER achievement is O (offering help) – which is also the most expensive for any government, as it requires longer-term investment and infrastructure. But instead of opening up all the possibilities of ‘offering help’, including ready access to SNP, politicians and policymakers around the world are being encouraged by ostensibly trustworthy sources to take up arms in the war against nicotine.

- Chretien, S. (2017, December 12). Up In Smoke: What Happened to the Tobacco Master Settlement Agreement Money? Citizens Against Government Waste. https://www.cagw.org/thewastewatcher/smoke-what-happened-tobacco-mastersettlement- agreement-money

- Minton, M. (2018). Fear Profiteers. How E-cigarette Panic Benefits Health Activists. (Issue Analysis). Competitive Enterprise Institute. https://cei.org/content/fear-profiteers

- Those who campaigned against slavery in the 19th century and more recently, climate change, environmental damage, racism and many other issues of ethics and conscience are beacon examples of how moral entrepreneurs can be a force for good. This contrasts with the intentions of those campaigning against tobacco harm reduction.

- Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1974). Judgment under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases. Science, 185(4157), 1124–1131. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.185.4157.1124

- Snowdon, C. (2009). Velvet Glove, Iron Fist: A History of Anti-Smoking. Little Dice. P.167

- Glantz, S. (2015, March 14). Meta-analysis of all available population studies continues to show smokers who use e-cigs less likely to quit smoking. Center for Tobacco Control Research and Education. https://tobacco.ucsf.edu/meta-analysisall- available-population-studies-continues-show-smokers-who-use-e-cigs-less-likely-quit-smoking

- https://web.archive.org/web/20151026231500/truthinitiative.org/sites/default/files/2015.06.30%20E-Cig%20FDA%20 Workshop%20Docket%20FINAL.pdf – p.12

- Kalkhoran, S., & Glantz, S. A. (2016). E-cigarettes and smoking cessation in real-world and clinical settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet. Respiratory Medicine, 4(2), 116–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(15)00521-4

- Expert reaction to meta-analysis looking at e-cigarette use and smoking cessation. (2016, January 14). Science Media Centre. https://www.sciencemediacentre.org/expert-reaction-to-meta-analysis-looking-at-e-cigarette-use-and-smokingcessation/

- McDonald, J. (2020, February 20). Journal Retracts ‘Unreliable’ Glantz Study Tying Vaping to Heart Attacks. Vaping360. https://vaping360.com/vape-news/88729/journal-retracts-unreliable-glantz-study-tying-vaping-to-heart-attacks/

- Berridge, V. (2007). Marketing Health: Smoking and the Discourse of Public Health in Britain, 1945-2000 (1 edition). Oxford University Press.

- Robert West et al. (2020). Trends in electronic cigarette use in England [Smoking Toolkit Study]. Smoking in England. http://www.smokinginengland.info/sts-documents/

- McNeill, A. et al. (2020). Vaping in England: an evidence update including mental health and pregnancy (Research and Analysis) [A report commissioned by Public Health England]. Public Health England (PHE). https://www.gov.uk/government/ publications/vaping-in-england-evidence-update-march-2020/vaping-in-england-2020-evidence-update-summary

- Poster presented at the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco conference 2018

- Vanquishing vaping? Support for tougher regulations rise as positive views of e-cigarettes go up in smoke. (2020, January 6). Angus Reid Institute. http://angusreid.org/vaping-trends-canada/

- Information for this section kindly provided by Michelle Minton of the Competitive Enterprise Institute, Washington.

- Kiviat, B., & Gates, B. (2008, July 31). Making Capitalism More Creative. Time. http://content.time.com/time/magazine/ article/0,9171,1828417,00.html

- http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/591281478711961885/pdf/The-Bloomberg-Family-Foundation-Inc-TF072332. pdf; http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/293351478711058473/pdf/Official-Documents-TF072332-Bill-and- Melinda-Gates-Foundation-Tobacco-Control-Program.pdf

- Reubi, D. (2018). Epidemiological accountability: philanthropists, global health and the audit of saving lives. Economy and Society, 47, 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/03085147.2018.1433359

- McGoey, L. (2012). Philanthrocapitalism and its critics. Poetics, 40(2), 185–199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.poetic.2012.02.006

- Mukaigawara, M. et al. (2018). Balancing science and political economy: Tobacco control and global health. Wellcome Open Research, 3, 40. https://doi.org/10.12688/wellcomeopenres.14362.1

- Youde, J. (2013). The Rockefeller and Gates Foundations in Global Health Governance. Global Society, 27, 139–158. https://doi.org/10.1080/13600826.2012.762341

- Patterson, A. S., & Gill, E. (2019). Up in smoke? Global tobacco control advocacy and local mobilization in Africa. International Affairs, 95(5), 1111–1130. https://doi.org/10.1093/ia/iiz102

- Patterson ibid.

- Paun, C. (2019, June 24). Big Pharma battles Big Tobacco over smokers. POLITICO. https://www.politico.eu/article/bigpharma- battles-big-tobacco-over-smokers/

- WHO. (2005). WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. World Health Organization. http://www.who.int/fctc/ text_download/en/. P. 3.

- Berridge, V. (2013). Demons: Our changing attitudes to alcohol, tobacco, and drugs. Oxford University Press. P. 176

- Dr Glover, personal communication.

- Smith, R. (2006). The Trouble with Medical Journals (1 edition). Routledge. P.85

- https://www.clivebates.com/; https://tobaccoanalysis.blogspot.com/; https://rodutobaccotruth.blogspot.com/; https://antithrlies.com/about/; http://www.ecigarette-research.org/research/

- ERS Position Paper on Tobacco Harm Reduction. A statement by the ERS Tobacco Control Committee. (2019, May). European Respiratory Society. https://www.ersnet.org/advocacy/eu-affairs/ers-position-paper-on-tobacco-harmreduction- 2019

- Britton, J. et al. (2020). A rational approach to e-cigarettes: challenging ERS policy on tobacco harm reduction. European Respiratory Journal, 55(5). https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.00166-2020

- This statement has since been removed from the site

- For full details, see Bates, C. (2020, January 30). World Health Organisation fails at science and fails at propaganda – the sad case of WHO’s anti-vaping Q&A. The Counterfactual. https://www.clivebates.com/world-health-organisation-failsat- science-and-fails-at-propaganda-the-sad-case-of-whos-anti-vaping-qa/

- Lancet editorial 28th May 2016, p.2136

- Hoffman, S. J. et al. (2019). Impact of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control on global cigarette consumption: quasi-experimental evaluations using interrupted time series analysis and in-sample forecast event modelling. BMJ, 365. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l2287

- Reubi, op cit. p.97

- Reubi op cit. p.100