Introduction

During the last few decades, Nordic countries have played host to dramatic falls in smoking rates. They are leading the way in Europe, and each showcases the potential for tobacco harm reduction to rapidly reduce cigarette use. But while snus has provided an increasingly popular off-ramp for those looking to switch away from smoking in Sweden and Norway, Icelanders have taken to a different selection of safer nicotine products, and this Briefing Paper uncovers the story of their rise.

What is the history of tobacco use in Iceland?

As with many European countries, tobacco arrived in Iceland in the 1600s,[1] with cigarettes becoming popular from the early part of the twentieth century. Snuff, intended for nasal use, but which Icelanders mostly take orally,[2] has been available since at least the 1940s,[3] and in recent years vapes and nicotine pouches have entered the market. Heated tobacco products are also available, but snus is illegal.

What are the impacts of tobacco use?

While smoking rates have been falling steadily in Iceland since at least the 1980s, tobacco smoking was associated with 17% of all fatalities in 2019.[4] Other research found 11.3% of all deaths in Iceland in 2021 were caused by tobacco use (13.5% for men and 9.2% for women).[5] The economic cost of smoking and tobacco use to Iceland each year is estimated to be more than 33 billion Iceland kronas (roughly £204 million or $269 million).[6]

What efforts have been made to address the use of cigarettes in Iceland?

Iceland has been a global leader in tobacco control legislation since the 1960s. In 1969, Iceland was the second country in the world to require health warning labels on packs of cigarettes.[7] In 1971, Iceland was the first country to ban tobacco advertising in mass media, cinemas and outdoors.[8] It was also the first country to implement graphic health warning labels in 1985,[9] and then, in 2001, the first to prohibit tobacco and tobacco trademarks being visible to consumers at the point of sale.[10]

Other measures included a smoke-free day, first held in 1979, as part of a national campaign to raise awareness among the public about the health risks of smoking. The government banned smoking in workplaces in 1984, made it illegal to sell tobacco to under 18s in 1996 and enacted a total ban on smoking in public places in 2007.[11] Iceland was also one of the first countries to ratify the World Health Organization’s Framework Convention on Tobacco Control in 2004.[12]

Since the 1970s, Iceland has invested in a range of activities aimed at bringing down smoking rates. In 1972, the warning labels on tobacco products were replaced by an earmarked tobacco tax which equalled 0.2% of gross nationwide tobacco sales.[13] The warning labels were thought to be failing to reach the target population of young Icelanders. Instead, this tax has been spent on directly educating children and students about the harmful effects of smoking on their health, as well as going towards advertising campaigns in the media. Then, in 2001, legislation was passed that increased this tax, meaning the government had to allocate at least 0.9% of gross tobacco sales to tobacco control, giving Iceland the highest spending on tobacco control per capita in Europe.[14] This led to Iceland being ranked third among European countries with the most comprehensive tobacco control policies in 2016,[15] though by 2021, it had fallen to eighth in the European Tobacco Control Scale.[16]

The Icelandic Model for Primary Prevention of Substance Use has also played a role in changing attitudes towards the use of tobacco. Launched in the 1990s, the model relies on “collaboration via community engagement, family and school involvement and pro-social positive youth development” to address substance use prevention collectively.[17] Since its implementation, the model has helped to develop “a consistent social norm among Icelandic youth that cigarette smoking and tobacco use are harmful and should be avoided at all costs”.[18]

How have smoking rates changed over time and how has public health been affected?

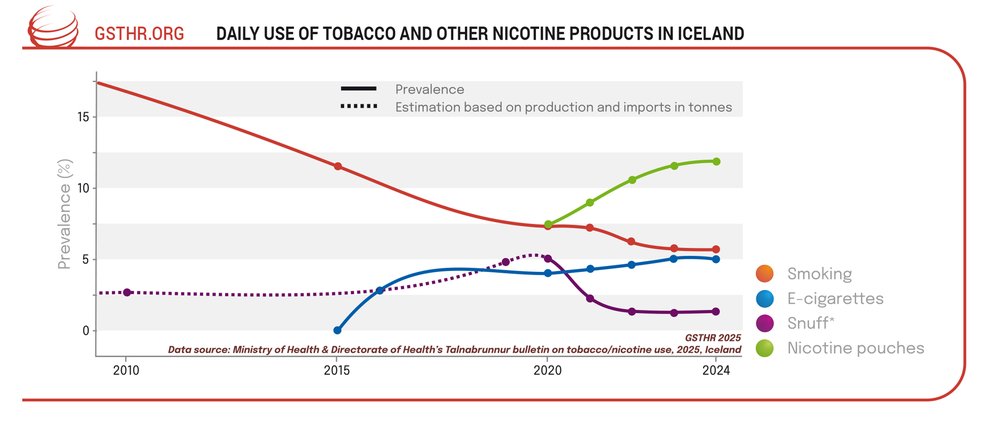

Annual surveys conducted by the Iceland Directorate of Health since 1989 show that smoking rates have been falling steadily over the last 35 years. In 1989, 34.2% of adults aged between 18 and 69 smoked daily.[19] By 2000, this had fallen to 25%. It dropped again to 11.5% in 2015 and the most recent survey, in 2024, revealed only 5.6% of Icelandic adults aged 18-69 smoke every day. It is anticipated that Iceland will soon gain smoke-free status, which is achieved when a country’s daily adult smoking rate is 5% or less.

This reduction in smoking has been linked to some significant public health gains. Between 1995 and 2015, the number of deaths due to smoking in Iceland was estimated to have reduced by a third.[20] Research also found that death rates from coronary heart disease fell by 80% for adults aged 25-74 between 1981 and 2006, with 22% of this reduction being due to reduced smoking prevalence.[21]

Other smoking-related diseases have similarly fallen in recent years. Data from the Global Burden of Disease Database reveals that when looking at both sexes together respiratory lung cancer mortality fell from just over 33 deaths per 100,000 in 2010 to just over 26 deaths per 100,000 in 2020.[22] But, more significantly, when just looking at respiratory lung cancer mortality for men, the rate has nearly halved, from a little over 40 deaths per 100,000 in the late 1980s to just over 22 deaths per 100,000 in 2020. It is a similar story for COPD mortality in Icelandic men, dropping from more than 25 deaths per 100,000 in 1986 to just over 14 deaths per 100,000 in 2020.

What are the most popular alternative nicotine products and how many people are using them?

While snus has played a significant role in reducing the number of smokers in fellow Nordic countries Norway and Sweden, this safer nicotine product is banned in Iceland. Although Iceland is not a member of the European Union (EU), it is part of the European Economic Area and has incorporated certain measures from the EU’s Tobacco Products Directive into its national legislation, including the banning of snus.

Until recently the most widely used oral nicotine product in Iceland was snuff tobacco.[23] This is a product intended for nasal use, but which many Icelanders take orally. It came to prominence in the 2010s, with reports in July 2014 showing its use had increased by 36% in the previous six months compared to the same period of 2013.[24] But just a few years later the sale of snuff fell from 46 tons in 2019 to 12.6 tons in 2022,[25] with the increasing popularity of nicotine pouches thought to be the main cause of this decline. The daily use of snuff has recently fallen from 5% of adults in 2020, to 1.2% 2023.[26]

In contrast, in 2024 almost 12% of Icelandic adults aged 18 and over were daily users of nicotine pouches, up from 9% in 2021.[27] This means nicotine pouches are now the most popular nicotine products in Iceland, with more than twice as many people using them compared to cigarettes. A total of 16.3% of men aged 18 and over used nicotine pouches each day in 2024, compared to 6.8% of women. And within the 18-34 age group, 32% of men and 21% of women were daily users. The 2024 data revealed that the daily use of nicotine pouches had increased in all age groups, except among those aged 55 and over. The use of nicotine vapes (e-cigarettes) has also been increasing during the last decade, rising from 2.8% of those aged 18 or more using them in 2016, to 5% in 2024.[28]

How are tobacco and safer nicotine products regulated and taxed?

Cigarettes and snuff are regulated by the Tobacco Control Act, whereas nicotine pouches and vapes come under the Act on nicotine products, e-cigarettes, and refills for e-cigarettes,[29] with nicotine pouches being added to this Act in 2022 due to concerns about their increasing take up by young people. For nicotine pouches, this means a ban on advertising, an age limit of 18 years, and a ban on use in places where children and young people are present. The law also allows for flavours in nicotine pouches to be banned, but this has not yet been adopted.

The legal age for buying nicotine vapes is also 18 and the products must display a health warning. But while packaging does not need to be plain, it may not appeal to minors. Flavours are not regulated. The advertising and promotion of vapes is generally prohibited, but product display is allowed at special retail outlets selling only vapes and associated products. The use of vapes is not allowed at places where activities for children and young people take place. As described earlier in this Briefing Paper, it became illegal to sell tobacco to under 18s in Iceland in 1996, and a total ban on smoking in public places was enacted in 2007.

Regarding taxation, from the start of 2025, a pack of 20 cigarettes became subject to tax of ISK 758.95 (around £4.60 or $6.20).[30] For reference, a pack of 20 Marlboro cigarettes costs on average ISK 1,650 (around £10.50 or $13.50).[31]

Since the beginning of 2025, nicotine pouches are now subject to taxes that vary depending on the amount of nicotine they contain. This ranges from ISK 8 (£0.05 or $0.07) per gram of pouch for those with low levels of nicotine, to ISK 20 (£0.12 or $0.16) per gram of pouch for those containing the highest levels of 16.1-20 mg of nicotine per gram.[32] Iceland is also the only Nordic country to have so far put a limit on the level of nicotine that pouches can contain, which is 20 milligrams of nicotine per gram of product.[33]

E-liquids containing 12 milligrams of nicotine or less are taxed at ISK 40 (around £0.25 or $0.33) per millilitre of e-liquid, while those containing more than 12 milligrams of nicotine are taxed at ISK 60 (£0.36 or $0.50) per millilitre of e-liquid.[34]

As well as the increasing availability of nicotine pouches in Iceland, part of their recent growth, at the expense of snuff, appears to be the result of them coming under different tax schedules.[35] These differences have led to nicotine pouches being a significantly cheaper option, costing an average of ISK 40 per gram (around £0.25 or $0.33), compared to snuff at ISK 80 per gram (around £0.50 or $0.65).[36]

Key takeaways and look to the future

Iceland has one of the lowest adult smoking rates in the world, thanks in part to an early adoption of tobacco control measures and prolonged investment in anti-smoking education. And, as with the success of snus in Sweden and Norway, it is oral safer nicotine products that Icelanders have taken to most readily as the country switches away from smoking. Firstly, Icelanders began to use snuff, taken orally instead of nasally, then, as safer alternatives, nicotine pouches and vapes, became available, these products have quickly taken hold. Now, twice as many people use nicotine pouches compared to cigarettes, and there are almost as many people who vape as smoke. More research is needed to track these transitions, but it appears that many Icelanders have switched from smoking to snuff, then from snuff to nicotine pouches, each time moving along the continuum of risk, progressing from more dangerous to the less harmful nicotine products.

This shows what can be achieved when safer nicotine products are available, accessible, affordable, appropriate and acceptable. But concerns about the number of young people using nicotine pouches look set to slow their rise. While cigarettes are taxed significantly more than all safer nicotine products, the recent change to tax nicotine pouches in line with the level of nicotine they contain, appears to be having an effect. The Iceland Directorate of Health says initial results from its monitoring indicate that the use of nicotine pouches actually went down in the first quarter of 2025.[37] A key part of the growth of nicotine pouches was their relative affordability compared to snuff, and it is important that Iceland’s government continues to ensure the taxation of safer nicotine products remains at a level that incentivises their use over more harmful alternatives.

For further information about the Global State of Tobacco Harm Reduction’s work, or the points raised in this GSTHR Briefing Paper, please contact [email protected]

About us: Knowledge·Action·Change (K·A·C) promotes harm reduction as a key public health strategy grounded in human rights. The team has over forty years of experience of harm reduction work in drug use, HIV, smoking, sexual health, and prisons. K·A·C runs the Global State of Tobacco Harm Reduction (GSTHR) which maps the development of tobacco harm reduction and the use, availability and regulatory responses to safer nicotine products, as well as smoking prevalence and related mortality, in over 200 countries and regions around the world. For all publications and live data, visit https://gsthr.org

Our funding: The GSTHR project is produced with the help of a grant from Global Action to End Smoking (formerly known as Foundation for a Smoke-Free World), an independent, US non-profit 501(c)(3) grant-making organisation, accelerating science-based efforts worldwide to end the smoking epidemic. Global Action played no role in designing, implementing, data analysis, or interpretation of this Briefing Paper. The contents, selection, and presentation of facts, as well as any opinions expressed, are the sole responsibility of the authors and should not be regarded as reflecting the positions of Global Action to End Smoking.

[1] Lucas, G., & Jónsson, J. (2024). Smoke, Sniff, Chew. Tobacco Consumption in Iceland During the Seventeenth-Nineteenth Centuries (pp. 141–155). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-71257-9_6.

[2] Júlíusson, Þ. S. (2017, August 1). ÁTVR greinir ekki á milli munntóbaks og neftóbaks. Kjarninn. https://kjarninn.is/skyring/2017-07-31-atvr-greinir-ekki-milli-munntobaks-og-neftobaks/.

[3] Icelandic Snuff Sales Hurt By Pouches. (2024, May 24). Tobacco Reporter. https://tobaccoreporter.com/2024/05/24/icelandic-snuff-sales-hurt-by-pouches/

[4] Iceland: Country Health Profile 2023. (2023). [Country profile]. European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies. https://eurohealthobservatory.who.int/publications/m/iceland-country-health-profile-2023.

[5] Iceland. (n.d.-a). Tobacco Atlas. Retrieved 9 September 2025, from https://tobaccoatlas.org/factsheets/iceland/.

[6] ‘Iceland’, n.d.-a.

[7] Hiilamo, H., Crosbie, E., & Glantz, S. A. (2014). The evolution of health warning labels on cigarette packs: The role of precedents, and tobacco industry strategies to block diffusion. Tobacco Control, 23(1), 10.1136/ tobaccocontrol-2012–050541. https://doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2012-050541.

[8] Ltd, B. P. G. (2007). Iceland: A pioneer’s saga. Tobacco Control, 16(6), 364–364. https://tobaccocontrol.bmj.com/content/16/6/364.1.

[9] Hiilamo, Crosbie, & Glantz, 2014.

[10] Scheffels, J., & Lavik, R. (2013). Out of sight, out of mind? Removal of point-of-sale tobacco displays in Norway. Tobacco Control, 22(e1), e37–e42. https://doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050341.

[11] Andersen, K. (2013). Country report Iceland—December 2013. European Society of Cardiology (EACPR). https://www.escardio.org/static-file/Escardio/Subspecialty/EACPR/iceland-country-report.pdf.

[12] Iceland. (n.d.-b). Health Promotion Fund Resource Hub. Retrieved 9 September 2025, from https://hpfhub.info/using-health-promotion-funding/what-is-the-impact-of-a-dedicated-fund/iceland/.

[13] ‘Iceland’, n.d.-b.

[14] OECD, European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, & European Commission. (2019). Iceland: Country Health Profile 2019 – State of Health in the EU. OECD Publishing / European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies. https://health.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2019-11/2019_chp_is_english_0.pdf.

[15] Joossens, L., & Raw, M. (2017). The tobacco control scale 2016 in Europe. [Report]. Association of European Cancer Leagues. https://www.drugsandalcohol.ie/28938/.

[16] Results 2021—Tobacco Control Scale. (2022). https://tobaccocontrolscale.org/results-2021/.

[17] Meyers, C. C. A., Mann, M. J., Thorisdottir, I. E., Ros Garcia, P., Sigfusson, J., Sigfusdottir, I. D., & Kristjansson, A. L. (2023). Preliminary impact of the adoption of the Icelandic Prevention Model in Tarragona City, 2015– 2019: A repeated cross-sectional study. Frontiers in Public Health, 11, 1117857. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1117857.

[18] Raitasalo, K., Bye, E. K., Pisinger, C., Scheffels, J., Tokle, R., Kinnunen, J. M., Ollila, H., & Rimpelä, A. (2022). Single, Dual, and Triple Use of Cigarettes, e-Cigarettes, and Snus among Adolescents in the Nordic Countries. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(2), 683. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19020683.

[19] Tobacco Use—Statistics. (n.d.). Ísland.Is. Retrieved 9 September 2025, from https://island.is/en/tobaksnotkun-tolur.

[20] ‘Iceland’, n.d.-b.

[21] Aspelund, T., Gudnason, V., Magnusdottir, B. T., Andersen, K., Sigurdsson, G., Thorsson, B., Steingrimsdottir, L., Critchley, J., Bennett, K., O’Flaherty, M., & Capewell, S. (2010). Analysing the large decline in coronary heart disease mortality in the Icelandic population aged 25-74 between the years 1981 and 2006. PloS One, 5(11), e13957. https:// doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0013957.

[22] https:/GBD Results. (n.d.). Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. Retrieved 9 September 2025, from https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-results/

[23] Embætti landlæknis, Viðar Jensson, & Sveinbjörn Kristjánsson. (2025). Talnabrunnur tbl4—Notkun tóbaks og nikótíns árið 2024. Embætti landlæknis. https://assets.ctfassets.net/8k0h54kbe6bj/LxD0d1JdNAirazkZP0uON/376357c56f09d1a49921353f99bbf174/Talnabrunnur_tbl4_2025.pdf.

[25] Embætti landlæknis. (2023). Talnabrunnur – Fréttabréf landlæknis um heilbrigðisupplýsingar (febrúar 2023). Embætti landlæknis. https://assets.ctfassets.net/8k0h54kbe6bj/1a2qWEi3eA9sBF4SYuXPbK/370008b44aabdda735fe6b311cd591a7/Talnabrunnur_februar_2023.pdf.

[26] Hrólfsson, R. J. (2024, February 11). Einn af hverjum þremur ungum körlum notar nikótínpúða daglega—RÚV.is. RÚV. https://www.ruv.is/frettir/innlent/404763.

[27] Embætti landlæknis, Viðar Jensson, & Sveinbjörn Kristjánsson, 2025.

[28] Embætti landlæknis, Viðar Jensson, & Sveinbjörn Kristjánsson, 2025.

[29] Regulations across the nordic and baltic countries—Use of nicotine products among youth in the nordic and baltic countries. (n.d.). Nordic Welfare Center. Retrieved 9 September 2025, from https://nordicwelfare.org/pub/Use_of_nicotine_products_among_youth_in_the_Nordic_and_Baltic_countries_-_An_overview/regulations-across-the-nordic-and-baltic-countries.html.

[30] Regulations across the nordic and baltic countries—Use of nicotine products among youth in the nordic and baltic countries, n.d.

[31] Cost of living in Iceland in 2025: Clothing, Food, Housing & More. (n.d.). Wise. Retrieved 9 September 2025, from https://wise.com/gb/cost-of-living/iceland.

[32] Regulations across the nordic and baltic countries—Use of nicotine products among youth in the nordic and baltic countries, n.d.

[33] European Commission (TRIS system). (2024). Government proposal to the Parliament for an Act amending the Tobacco Act (TRIS notification No 25642). European Commission (Notification via TRIS). https://technical-regulation-information-system.ec.europa.eu/sk/notification/25642/text/D/EN.

[34] Regulations across the nordic and baltic countries—Use of nicotine products among youth in the nordic and baltic countries, n.d.

[35] Pomrenke, E. (2024, May 23). State Alcohol and Tobacco Company to Snuff Out Snuff Production. Iceland Review. https://www.icelandreview.com/news/state-alcohol-and-tobacco-company-to-snuff-out-snuff-production/.

[36] Pomrenke, 2024.

[37] Embætti landlæknis, Viðar Jensson, & Sveinbjörn Kristjánsson, 2025.